Take a look at the video above and the associated question – What did they hold before opening the closet?. After looking at the video, you can easily answer that the person is holding a phone. People have a remarkable ability to comprehend visual events in new videos and to answer questions about that video. We can decompose visual events and actions into individual interactions between the person and other objects. For instance, the person initially holds a phone and then opens the closet and takes out a picture. To answer this question, we need to recognize the action “opening the closet” and then understand how “before” should restrict our search for the answer to events before this action. Next, we need to detect the interaction “holding” and identify the object being held as a “phone” to finally arrive at the answer. We understand questions as a composition of individual reasoning steps and videos as a composition of individual interactions over time.

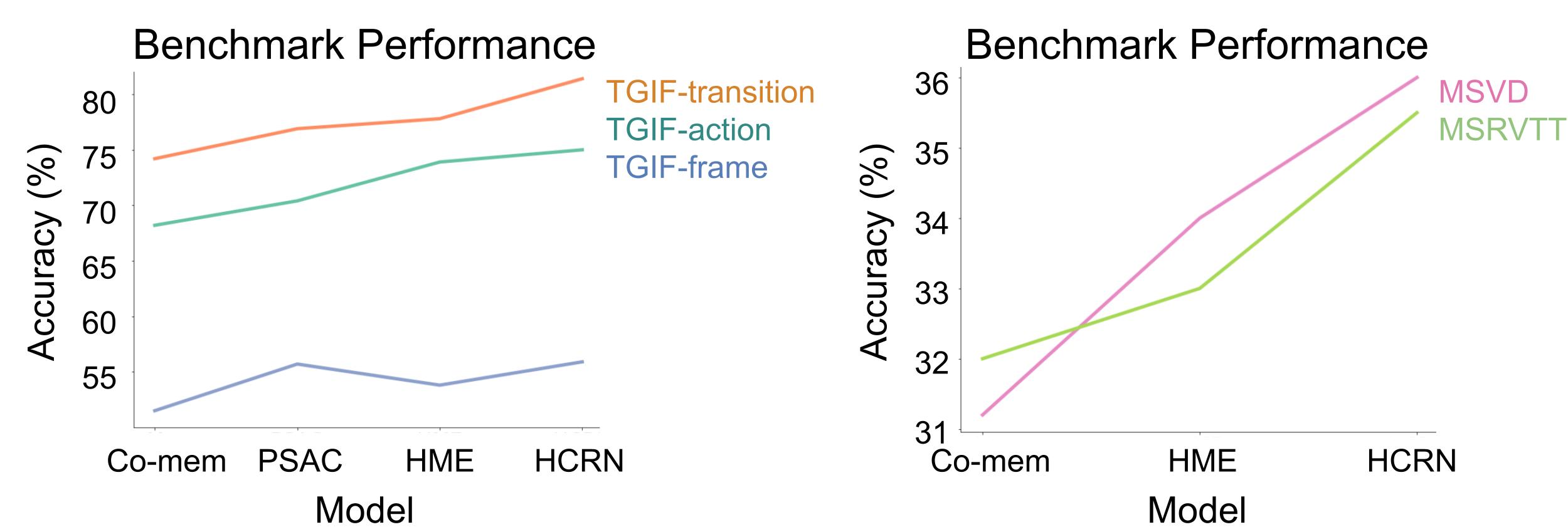

Designing machines that can similarly exhibit compositional understanding of visual events has been a core goal of the computer vision community. To measure progress towards this goal, the community has released numerous video question answering benchmarks (TGIF-QA, MSVD/MSRVTT, CLEVRER, ActivityNet-QA). These benchmarks evaluate models by asking questions about videos and measure the models’ answer accuracy. Over the last few years, model performance on such benchmarks have been encouraging:

However, it is unclear why models are improving. Simple questions like “What did they hold before opening the closet?” require a composition of many different reasoning capabilities. Are the models improving at recognizing actions? On understanding interactions? Or are they just improving on exploiting linguistic and visual biases in the dataset? Since these benchmarks primarily offer a single “overall accuracy” metric as an evaluation measure, we have a limited view of each model’s strengths and weaknesses.

To better answer these questions, we introduce the benchmark Action Genome Question Answering (AGQA). AGQA measures spatial, temporal, and compositional reasoning through nearly two hundred million question answering pairs. AGQA’s questions are complex, compositional, and annotated to allow for explicit tests that find the types of questions that models can and cannot answer.

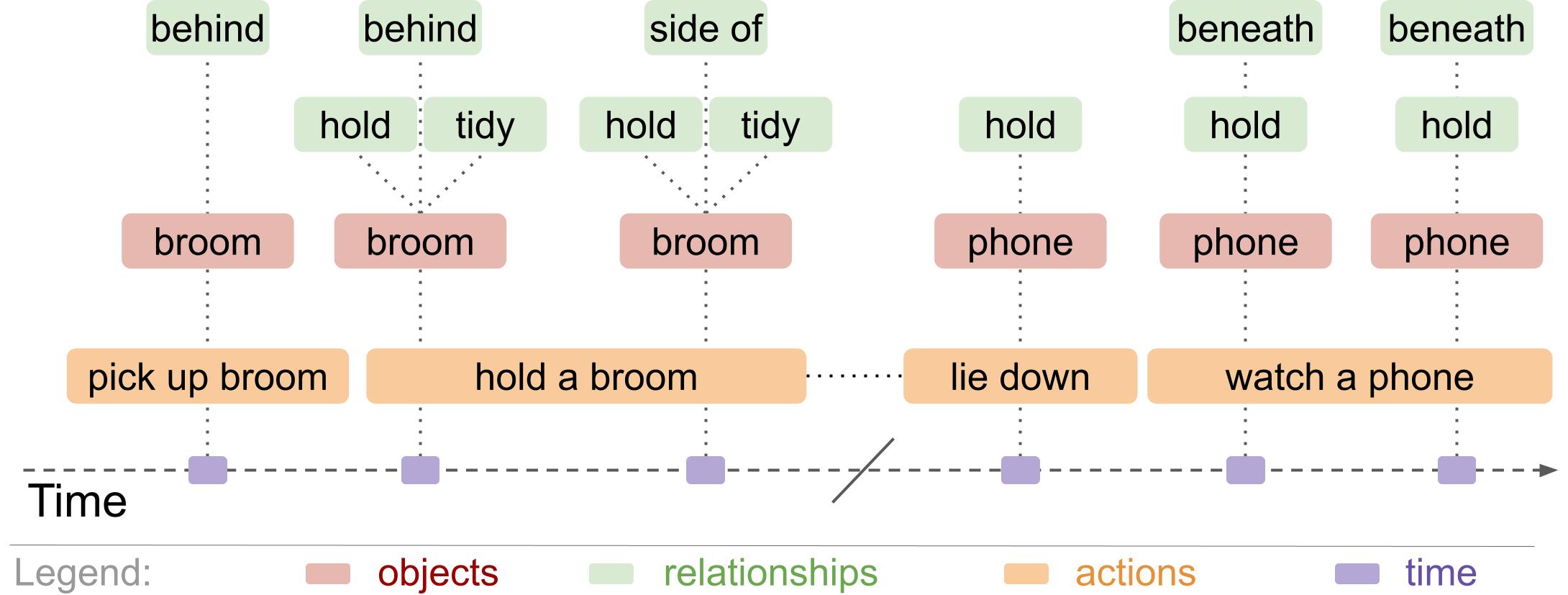

Creating a benchmark at this scale is prohibitively expensive to scale with human annotators. Instead, we design a synthetic generation process using rules-based question templates to generate questions from scene information, which represents what occurs in the video using symbols (Figure 3: spatio-temporal scene graphs from Action Genome). Synthetic generation allows us to control the content, structure, and compositional reasoning steps required to answer each generated question.

We ran state of the art models on our benchmark and found that they performed poorly, relied heavily on linguistic biases, and struggled to generalize to more complex tasks. In fact, all the models performed barely above an ablation where the video was not presented as an input at all.

Action Genome Question Answering (AGQA)

Action Genome Question Answering has 192 Million complex and compositional question-answer pairs. We also sample 3.9 Million question-answer pairs such that this subset has a more even distribution of answers and a wider diversity of questions. Each question has detailed annotations about the content in and structure of the question. These annotations include a program of the reasoning steps needed to answer the question and a mapping of items in the question to the relevant part of the video (Figure 4). AGQA also provides detailed metrics, including test splits to measure performance on different question types and three new metrics designed to measure compositional reasoning.

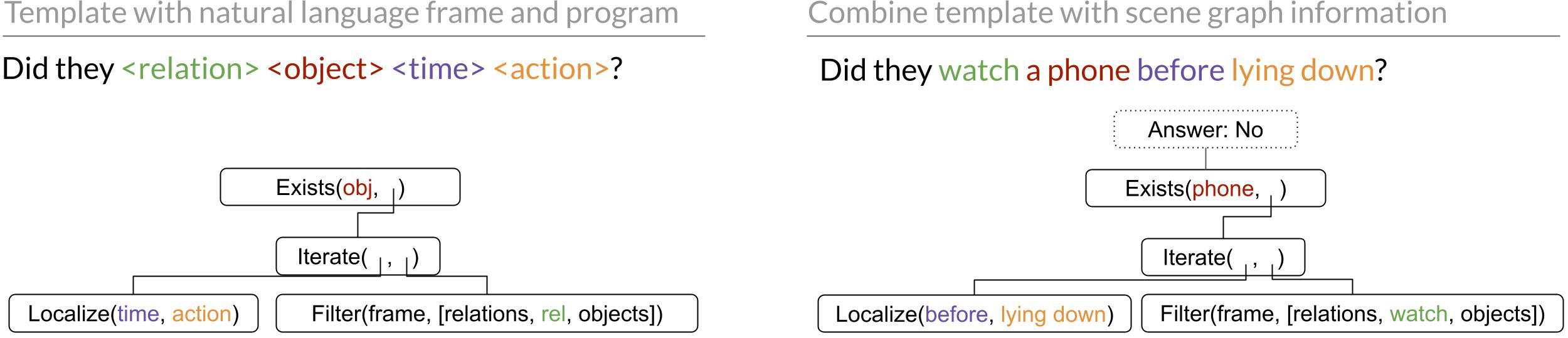

To synthetically generate questions, we first represent the video through scene graphs (Figure 3). We take a sample of frames from the video in which each frame annotates the actions, objects, and relationships that occur in that frame. Second, we built 28 templates. These templates include a natural language frame referencing types of items within the scene graphs. In Figure 4, the template provides a general natural language frame asking if the subject did a relationship on an object during a specified time period. Each template also has a program outlining a series of steps to follow in order to answer the question. The example in Figure 4 iterates over the time period, finds all the objects on which they had that relationship, then determines if the specified object exists within that list.

Third, we combine the scene graphs and the templates to generate natural language question-answer pairs. For example, the above template could use the scene graph from Figure 3 to generate the natural language question “Did they watch a phone before lying down?”. The associated program then automatically generates the answer by iterating over the time before they were lying down, finding all the items they were watching , and determining that they do not watch a phone during that time. Combining the scene graphs and templates creates a wide variety of natural language question-answer pairs. Each pair in our benchmark includes a reference to the program of reasoning steps used to generate the answer, as well as a mapping that grounds words in the question to the scene graph annotations. Finally, we take the generated pairs and balance the distributions of answer and question types. We smooth answer distributions for different categories then sample questions such that the dataset has a diversity of question structures.

AGQA evaluation

Human evaluation. We validate our question-answer pairs through human validation and find that annotators agree with 86.02% of our answers. To put this number in context, GQA and CLEVR , two recent automated benchmarks, report 89.30% and 92.60% human accuracy, respectively. Some scene graphs have inconsistent, incorrect, or missing information in the scene graphs that propagate into incorrect questions. There may also be differences between the ontologies of the scene graph and human understood definitions. For example, there are 36 objects in the scene graphs, but humans may consider objects that appear in the video but are not within the model’s purview.

We provide further detail on the human tasks, each of these error sources, and recommendations for future video representations in the supplementary section of our paper.

Model performance depends on linguistic biases. We run three state of the art models on our benchmark (HCRN, HME, and PSAC), and find that the models struggle on our benchmark. If the model only chose the most likely answer (“No”) it would achieve a 10.35% accuracy. The highest scoring model, HME, achieved a 47.74% accuracy, which at first glance appears to be a big improvement. However, further investigation found that much of the gain in accuracy comes from just exploiting linguistic biases instead of from visual reasoning. Although HCRN achieved 47.42% accuracy overall, it still achieved a 47% accuracy without seeing the videos. The fact that the model is so dependent on linguistic biases instead of visual reasoning reduces the ability of our other test splits to effectively measure visual reasoning for these particular models.

Measurement of different question attributes. We provide splits in the test set to measure model performance on different types of reasoning skills, semantic categories, and question structures.

To understand model performance on different types of questions, we split the test set by the reasoning skills needed to answer the question. For example, some questions test superlative concepts like first and last (What did they pick up first, a dish or a picture?), some compare the duration of multiple actions (Was the person eating some food or sitting on the floor for longer?), and others require activity recognition (What were they doing last?). Different models achieved the highest accuracy in each category. Model performance also varied widely among these categories, with all three models performing the worst on activity recognition.

AGQA also splits questions by if their semantic focus is on objects, relationships, or actions. Only choosing the most common answer would lead to a 9.38%, 50%, and 32.91% accuracy on questions about objects, relationships, and actions respectively. The highest performing models achieved a 42.48% accuracy for object-oriented questions, while the blind model achieved a 40.74% accuracy. The blind model outperformed all other models with a 67.40% accuracy for relationship-oriented questions, and a 60.95% accuracy on action-oriented questions.

Finally, we annotate each question by its structure. Query questions are open-answered (What did they hold?). Verify questions verify if a question is true (Did they hold a dish?). Logic questions use a logical operator (Did they hold a dish but not a blanket?). Choose questions offer a choice between two options (Did they hold a dish or a blanket?). Compare questions compare the attributes of two options (Compared to holding a dish, were they sitting for longer?). Every model performed the worst on open-answered questions and best on verify and logic questions.

New compositionality metrics. We also provide three new metrics that specifically measure compositional reasoning. These split the training and test sets to test the model’s ability to generalize to novel compositions of previously seen ideas, to indirect references, and to more compositional steps.

First, we measure a model’s ability to generalize to novel compositions. We consider a composition to be two discrete ideas, composed together into one instance. For example “before” and “standing up” are a composition in the question “What did they take before standing up?”. To ensure these compositions are novel in the test set, we include the ideas of before and standing up in the training set when they are composed with other items. However, we do not include questions in the training set in which the before-standing up composition occurs. The models struggle to generalize to the compositions they see for the first time in the test set. The best performing model barely achieves more than 50% accuracy on binary questions that have only two answers. On open answer questions that have more than two possible answers, the highest performing model achieves 23.72% accuracy.

Our second metric measures generalization to indirect references. Direct references state what they are referring to (a phone), while indirect references refer to something by its attributes or other relationships (the first thing they held). We use indirect references to increase the complexity of our questions. This metric compares how well models answer a question with indirect references if they can answer it with the direct reference. Models can answer approximately 80% of questions using indirect references if they could answer it with the direct reference.

The third compositionality metric measures generalization to more complex questions. A training and test split divides the questions such that the training set contains simpler questions with fewer compositional steps, while the test set includes questions with more compositional steps. The models struggle on this task, as none of them outperform 50% on binary questions, which have only two answers.

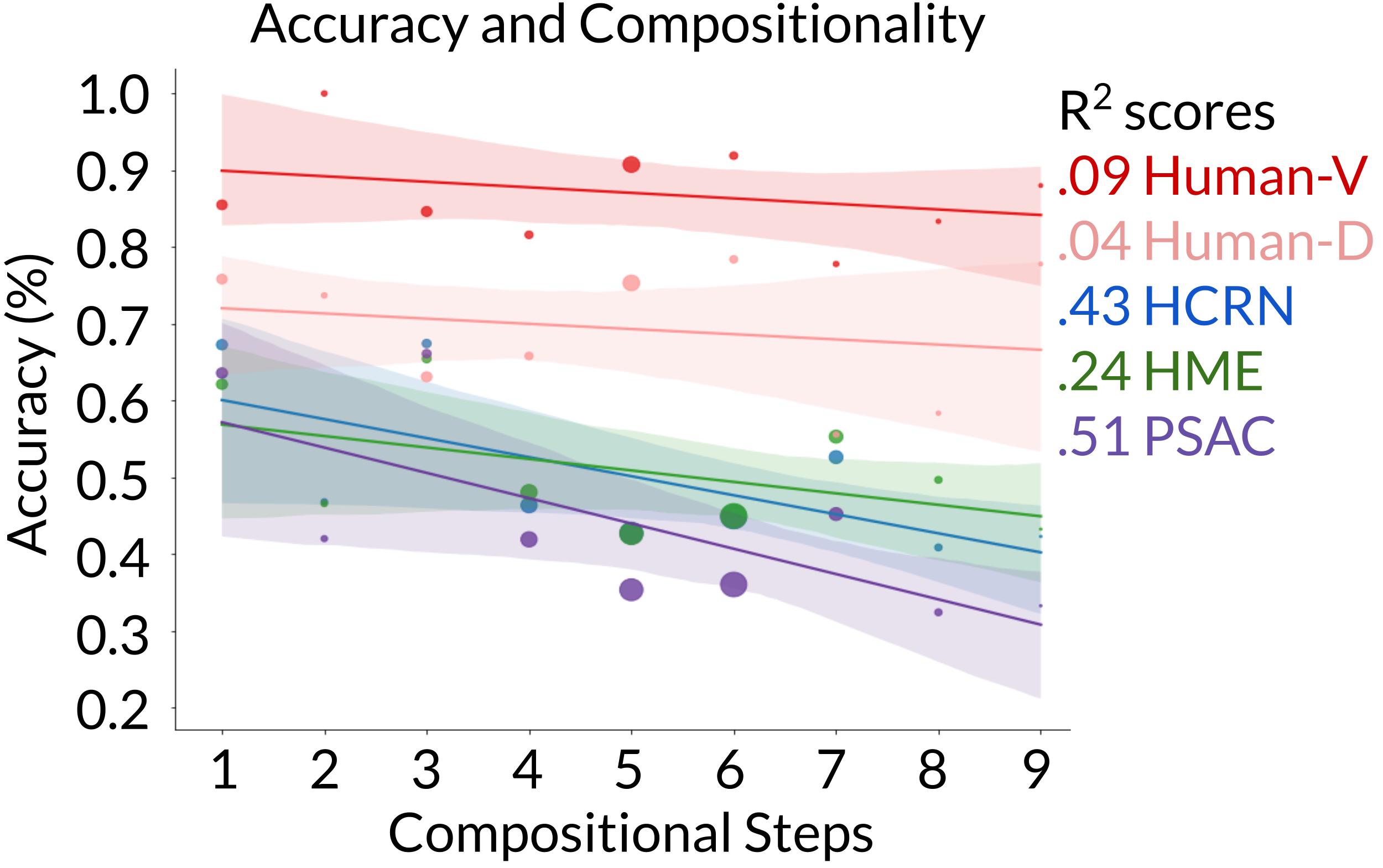

Question complexity and accuracy. Finally, we annotate the number of compositional steps needed to answer each question. We find that although humans remain consistent as questions become more complex, models decrease in accuracy.

Future work

AGQA opens avenues for progress in several directions. Neuro-symbolic and meta learning modeling approaches could improve compositional reasoning. The programmatic breakdown of questions could also inform work on generating explanations. We also invite exploration into employing and generating different symbolic representations of video.

Our benchmark highlights the weak points of existing models, including overreliance on linguistic biases and a difficulty generalizing to novel and more complex tasks. However, its balanced dataset of question answer pairs and detailed metrics provide a baseline for exploring multiple exciting new directions.

Find our paper here.

Find our benchmark data here.