Large datasets have been shown to facilitate robot intelligence. By collecting diverse datasets for tasks such as grasping and stacking, robots are able to learn from this data to grasp and stack challenging, novel objects they haven’t seen before.

While these results are impressive, they are still limited in critical ways compared to human intelligence. Today, robot intelligence is narrow-minded - they usually only find one way to solve a problem. By contrast, humans are really good at reasoning about creative ways to solve a problem and physically manipulating objects to make it happen.

How can we help our robots cross this gap in problem solving ability? We assert that one way is to let our robots learn from data that captures human intelligence. In this blog post, we describe how we built a data collection platform that enables collecting datasets that captures human intelligence.

What kind of data captures human intelligence?

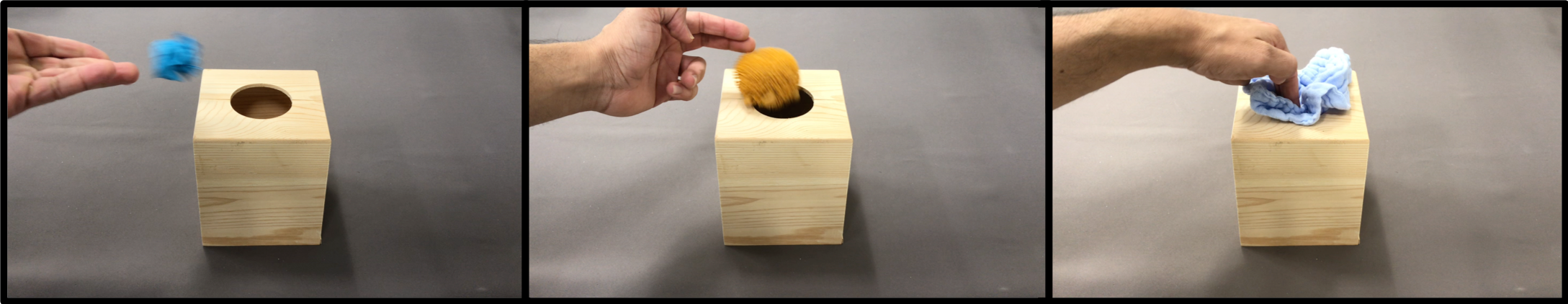

Diversity. The data should be diverse in the kinds of problem-solving strategies demonstrated. Consider the example below, where we would like to fit an item into a container. If the item is small, you could toss it in, and if it’s already near the container you could probably push it in. If it’s large, you would have to stuff it in. As humans, we have a good sense of when we should try these different approaches – robots should learn from all of these strategies – it might need any of them in a given situation.

Dexterity. The data should contain instances of dexterous manipulation so that the robot can learn fine-grained manipulation behaviors. We want our robots to understand how they can physically manipulate objects to achieve desired outcomes.

Large-Scale. Finally, there should be a large amount of data. This is important – we are very good at problem solving in countless situations, but robots aren’t able to do this yet. The more data we show them, the more likely that they’ll acquire this general problem-solving ability too.

Collecting data that captures human intelligence

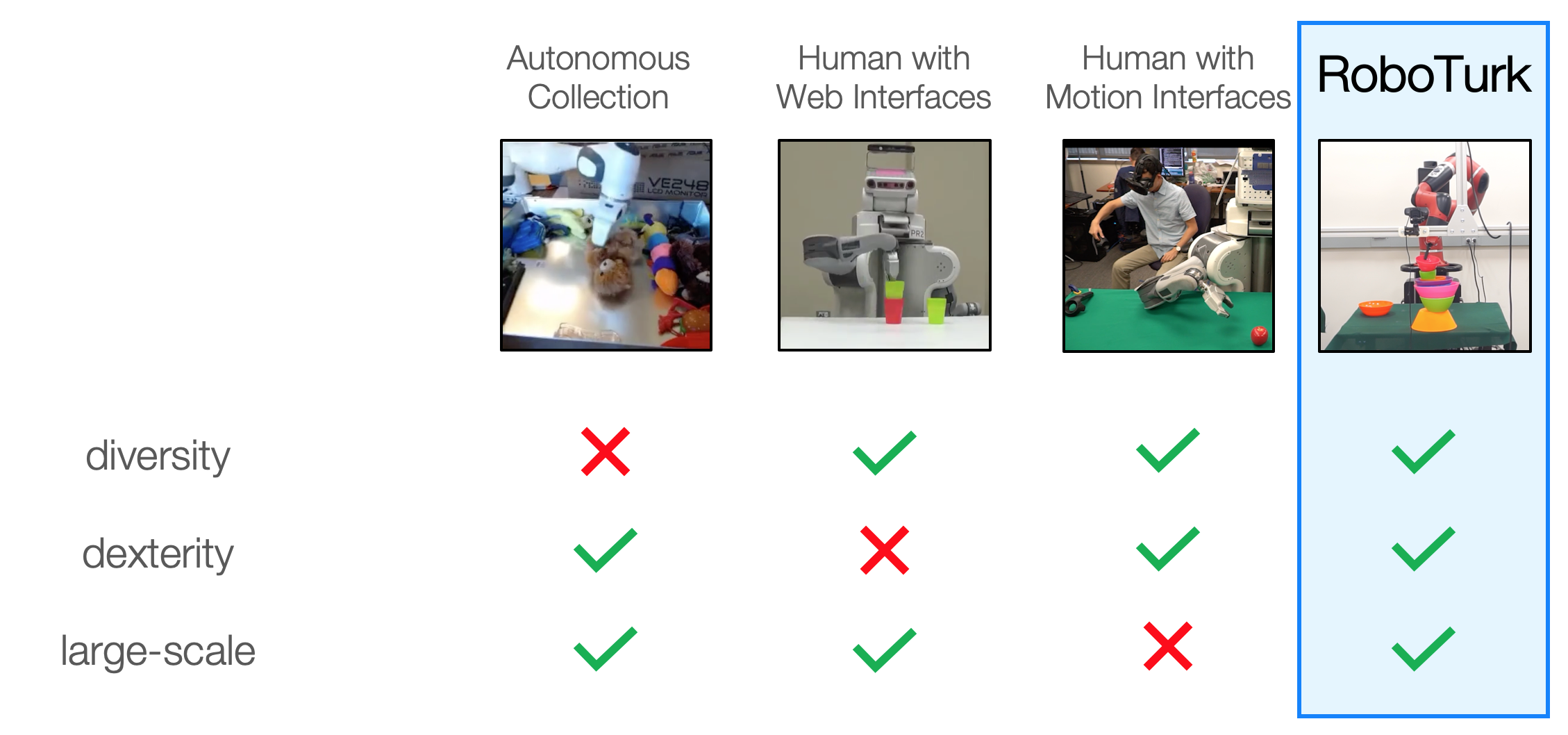

There are several methods that have been used to collect robotic data in the past. Here, we evaluate the ability of each method to collect desirable data for generalization.

- Autonomous Data Collection: Many data collection mechanisms and algorithms such as Self-Supervised Learning12 and Deep Reinforcement Learning3 use random exploration to collect their data. While this allows the robot to autonomously collect data, the data is strongly correlated and lacks diverse problem-solving strategies. This is because data is collected purely at random at first, and over time, methods converge to specific solution strategies.

- Human Supervision with Web Interfaces: By contrast, human supervision allows for direct specification of task solutions. Prior mechanisms4 have allowed humans to leverage graphical web interfaces to guide robots through tasks. While such data collection schemes allow for diverse data to be collected at scale through humans, the interfaces limit the dexterity of the robot motions that can be demonstrated. For example, in the middle video above, a user has specified a program for the robot to execute, and the robot takes care of picking up the cups using simple top-down grasps. The human does not have much of a say in how the task is done.

- Human Teleoperation with Motion Interfaces: Others have developed motion interfaces to enable a direct one-to-one mapping between human motion and the end effector of the arm. One such example5 is a person using a Virtual Reality headset and controller to guide the arm through a pick-and-place task. By offering users full control over how the arm accomplishes the task, these interfaces allow for data that is both diverse and dexterous. However, they do not allow for large-scale data collection, since the special hardware needed to develop such interfaces is not widely available.

Our goal was to develop a data collection mechanism that captures human intelligence by collecting data that has diverse problem-solving strategies, dexterous object manipulation, and that could be collected at scale. To address this challenge, we developed RoboTurk.

RoboTurk

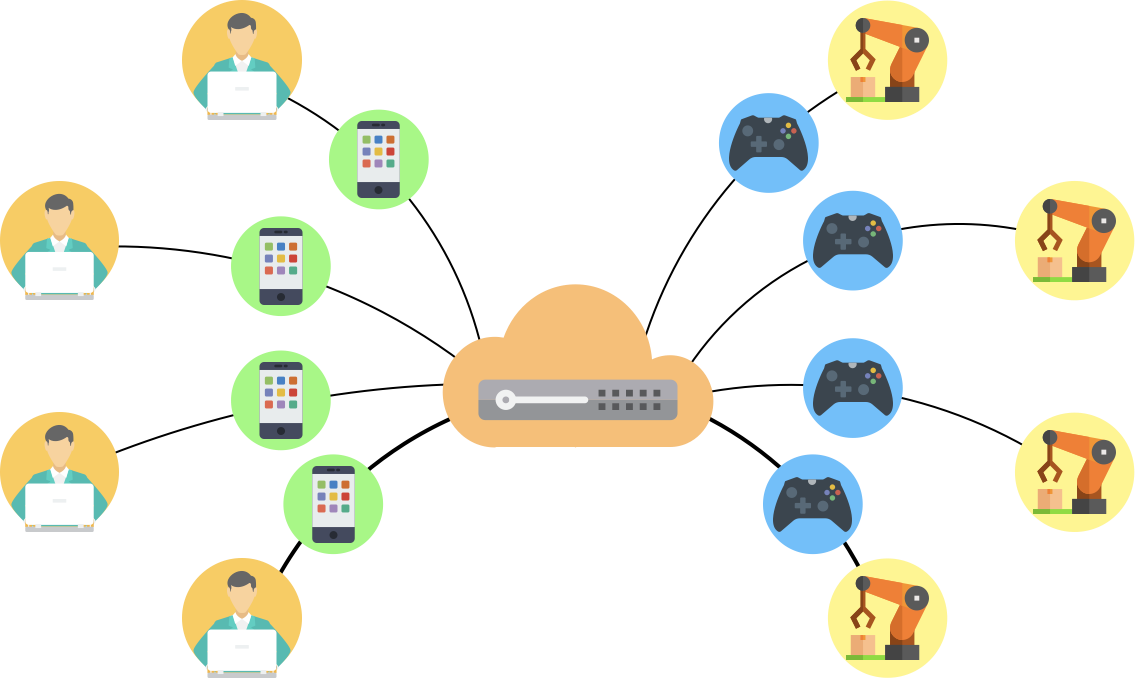

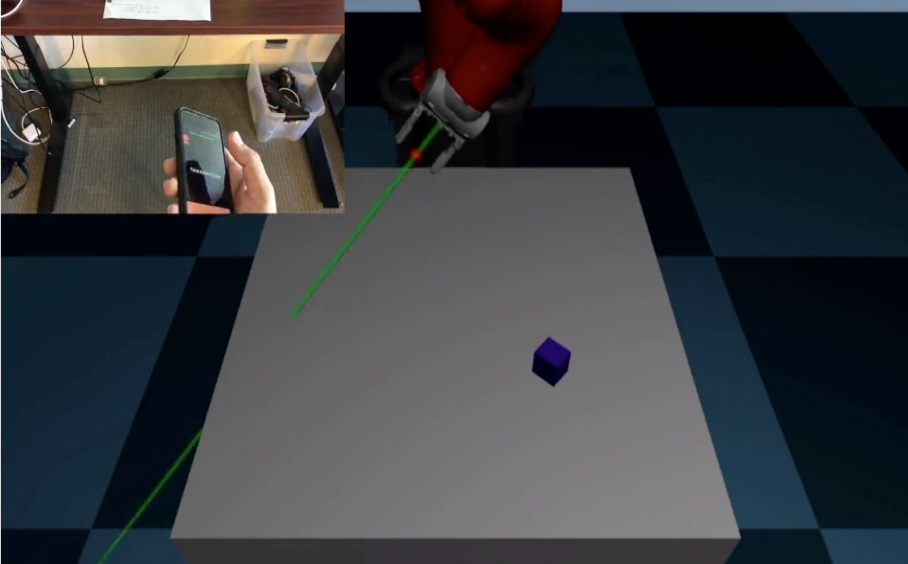

RoboTurk is a platform that allows remote users to teleoperate simulated and real robots in real-time with only a smartphone and a web browser. Our platform supports many simultaneous users, each controlling their own robot remotely. A new user can get started in less than 5 minutes - all they need to do is download our smartphone application and go to our website, and they are ready to start collecting data.

Our platform enables people to control robots in real-time from anywhere - libraries, cafes, homes, and even the top of a mountain.

User Interface to enable Dexterity

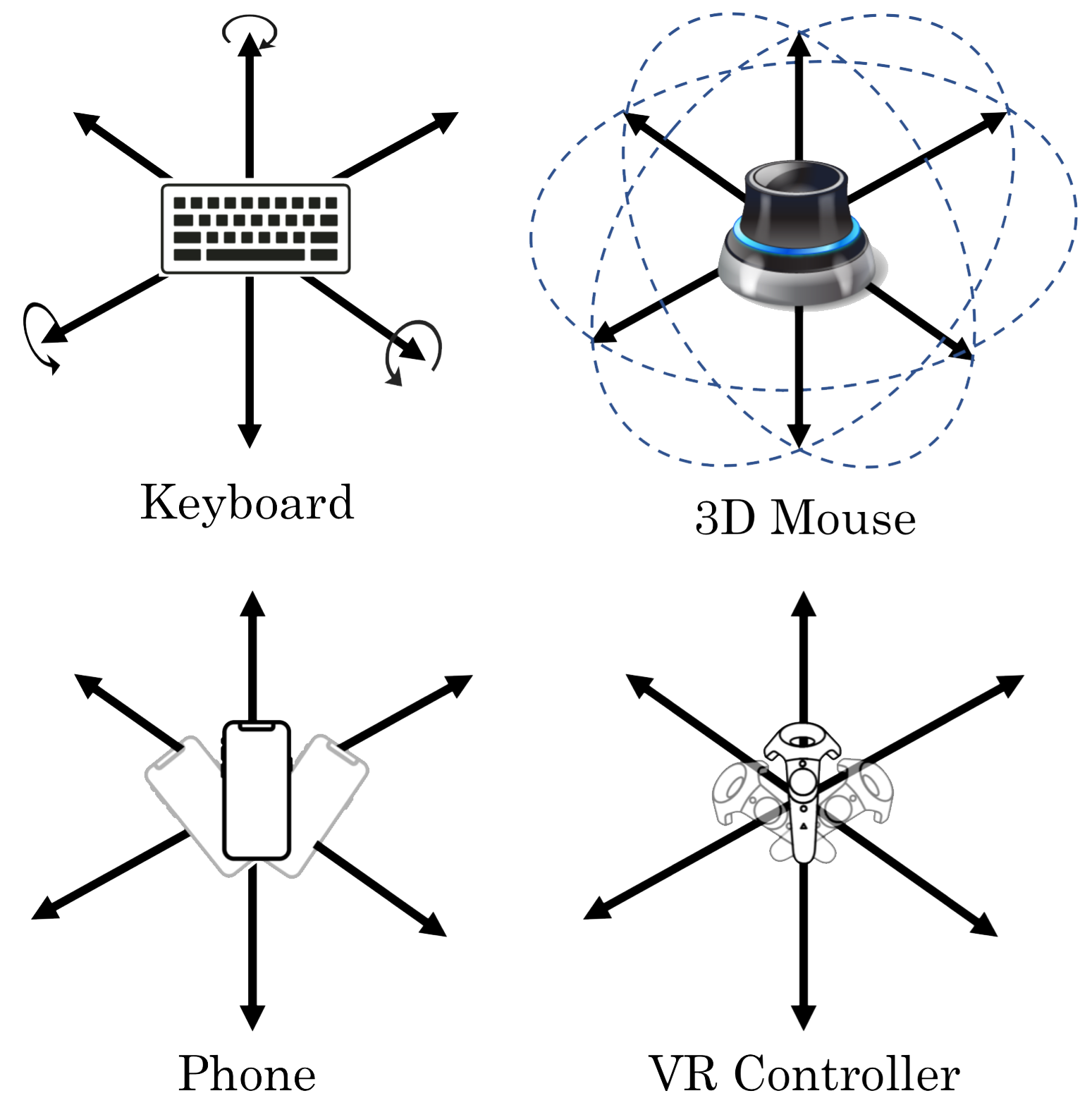

Users receive a video stream of the robot workspace in their web browser and use their phone to guide the robot through a task. The motion of the phone is coupled to the motion of the robot, allowing for natural and dexterous control of the arm.

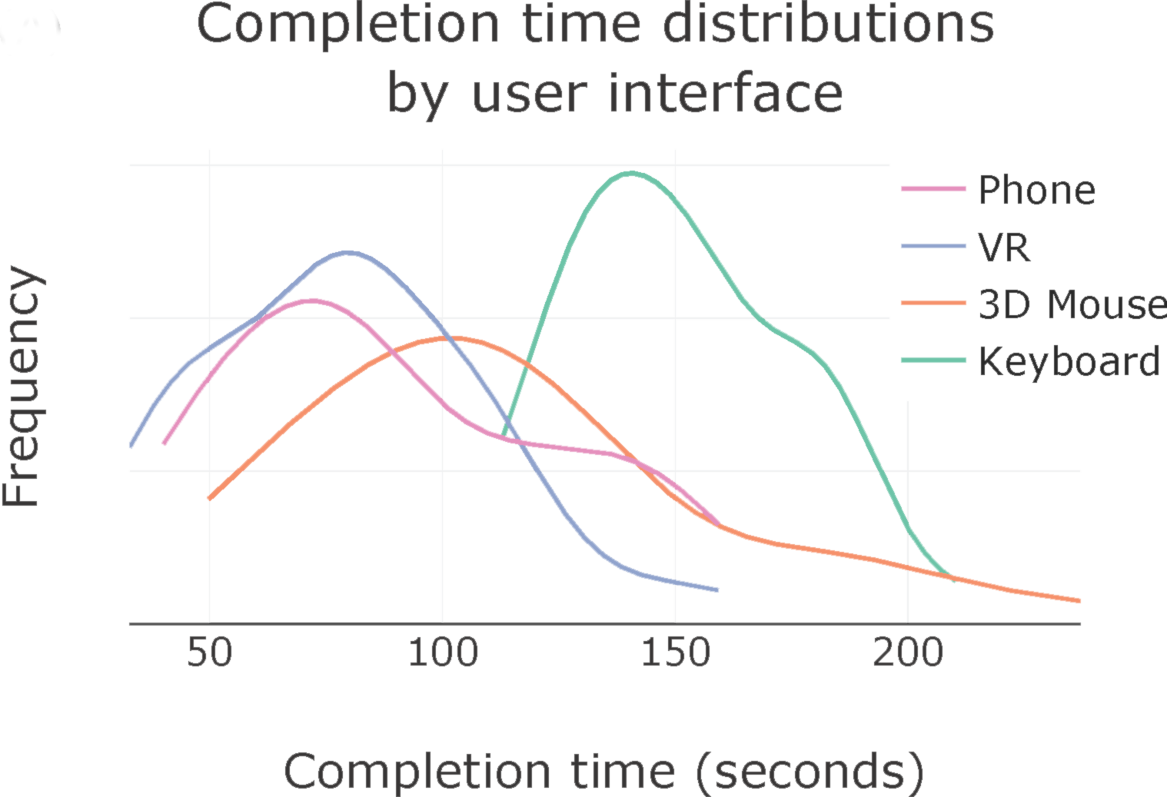

We conducted a user study and showed that our user interface compares favorably with virtual reality controllers, which use special external tracking for the controllers, and significantly outperforms other interfaces such as a keyboard and a 3D mouse. This demonstrates that our user interface is both natural for humans to efficiently complete tasks and scalable to ensure that anyone with a smartphone can participate in data collection.

Diversity through Worldwide Teleoperation

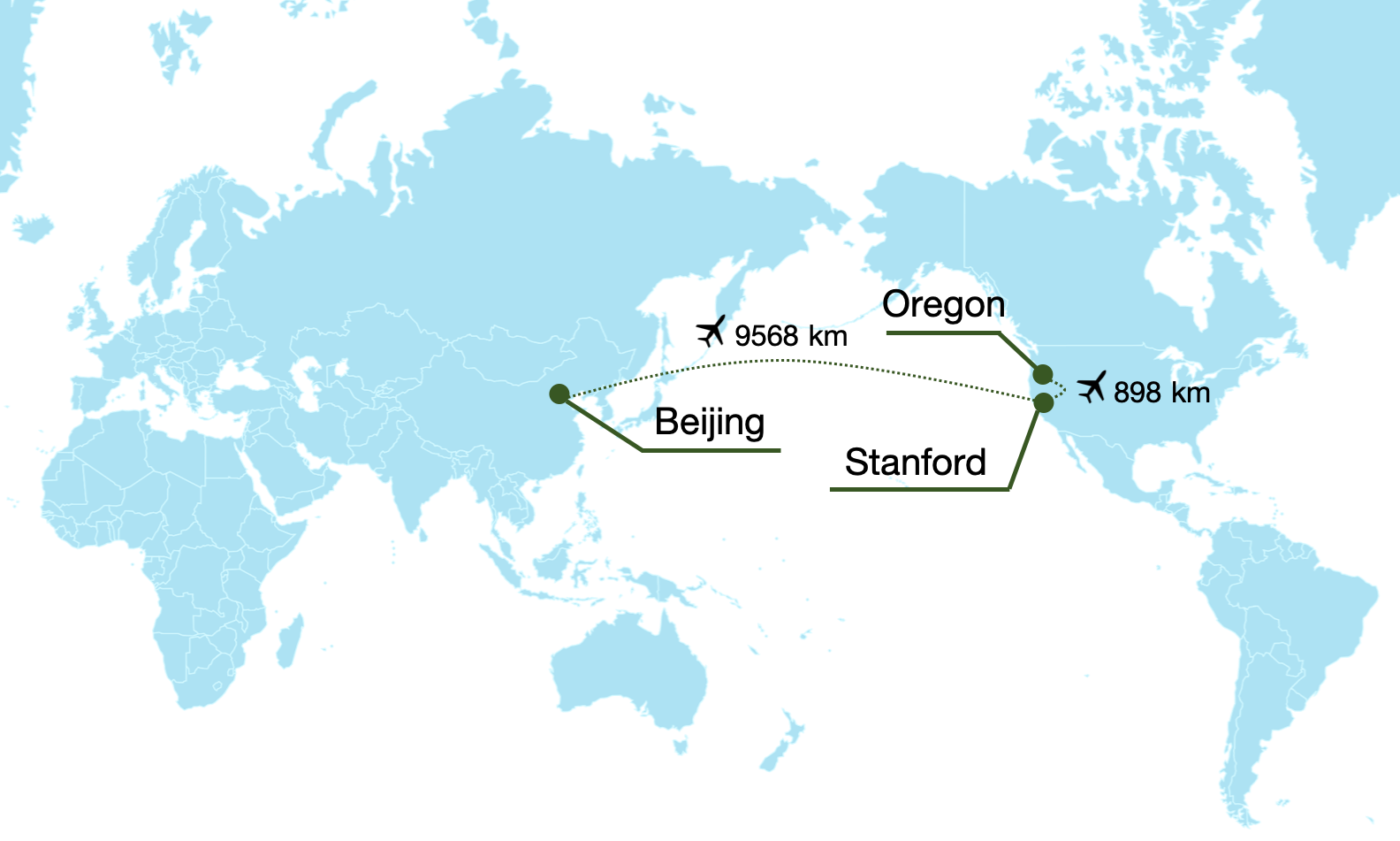

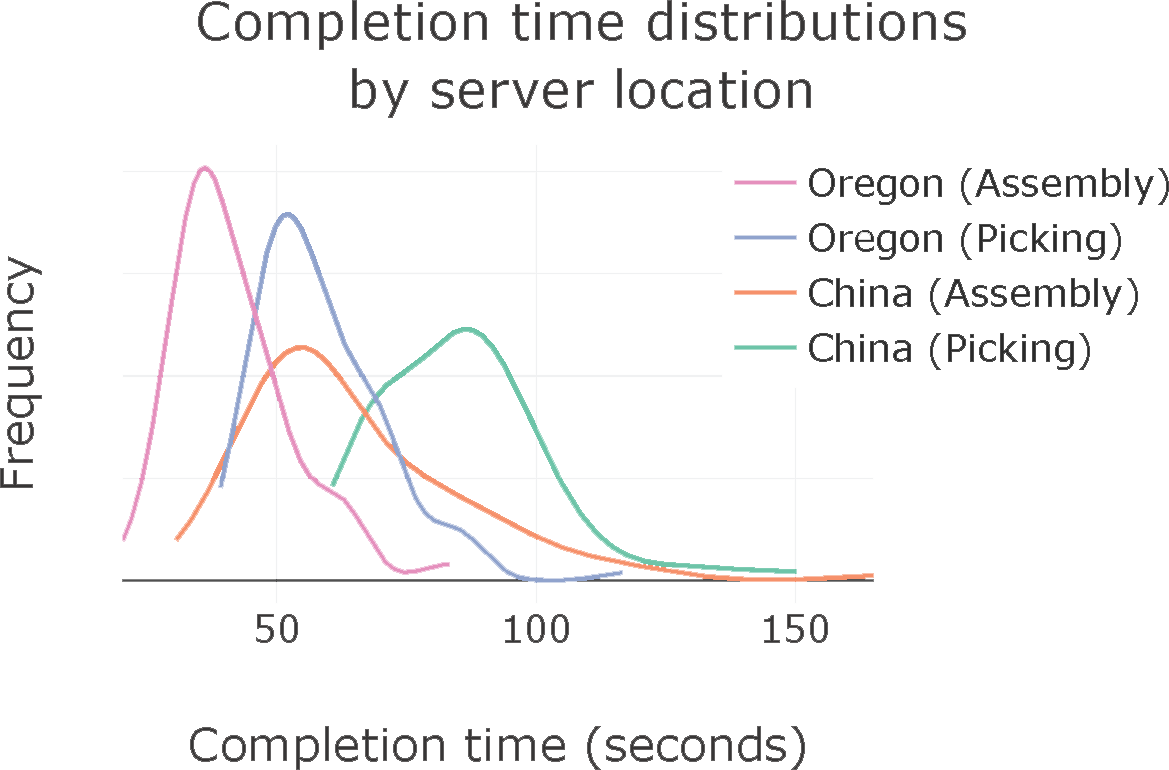

Enabling remote data collection with consumer-grade hardware allows many different people to easily provide data, naturally resulting in datasets that are diverse. To test the capability of RoboTurk to enable remote data collection, we tried controlling robot simulations hosted on servers in China from our lab in California, a distance of over 5900 miles! We found that is possible to collect quality demonstrations using RoboTurk regardless of the distance between user and server.

More recently, we tried teleoperating our physical robot arms located at Stanford from Macau. We found that our system provided real-time teleoperation of our robot arms even at a distance of over 11,000 km, all on a cellular network connection.

Large-Scale Data Collection

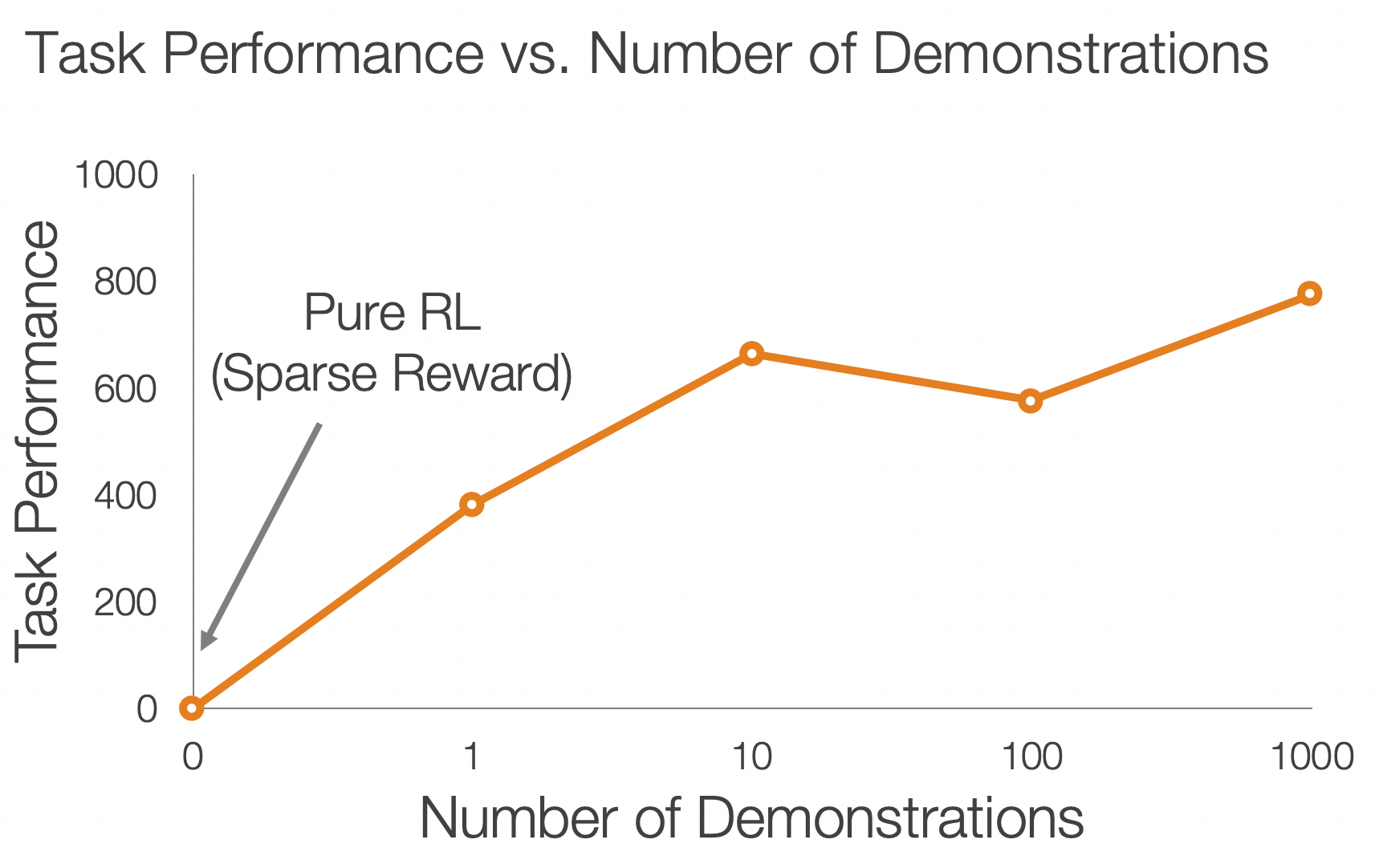

RoboTurk enables collect large amounts of data in a matter of hours. In our first publication, we used RoboTurk to collect a Pilot Dataset consisting of over 2000 task demonstrations in just 22 hours of total system usage. We also leveraged the demonstrations for policy learning and showed that using more demonstrations enables higher quality policies to be learned.

In summary, RoboTurk is able to collect data that embodies human intelligence:

- Diversity. RoboTurk can be used to collect diverse data by leveraging many simultaneous human users for data collection.

- Dexterity. RoboTurk offers full 6-DoF control of the robot arm through a natural phone interface, allowing for dexterity in the data.

- Large-Scale. RoboTurk allows for large-scale data collection by allowing people to collect data from anywhere using just a smartphone and web browser. Our pilot dataset was collected in just 22 hours of system operation.

Collecting Data on Physical Robots

In our initial publication, we used RoboTurk to collect a large dataset using robot manipulation tasks developed using MuJoCo and robosuite. However, there are several interesting tasks that cannot be modeled in simulation, and we did not want to restrict ourselves to those that could. Thus, we extended RoboTurk to enable data collection with real robot arms, and used it to collect the largest robot manipulation dataset collected via teleoperation.

The dataset consists of RGB images from a front-facing RGB camera (which is also the teleoperator video stream view) at 30Hz, RGB and Depth images from a top-down Kinectv2 sensor also at 30Hz, and robot sensor readings at 100Hz.

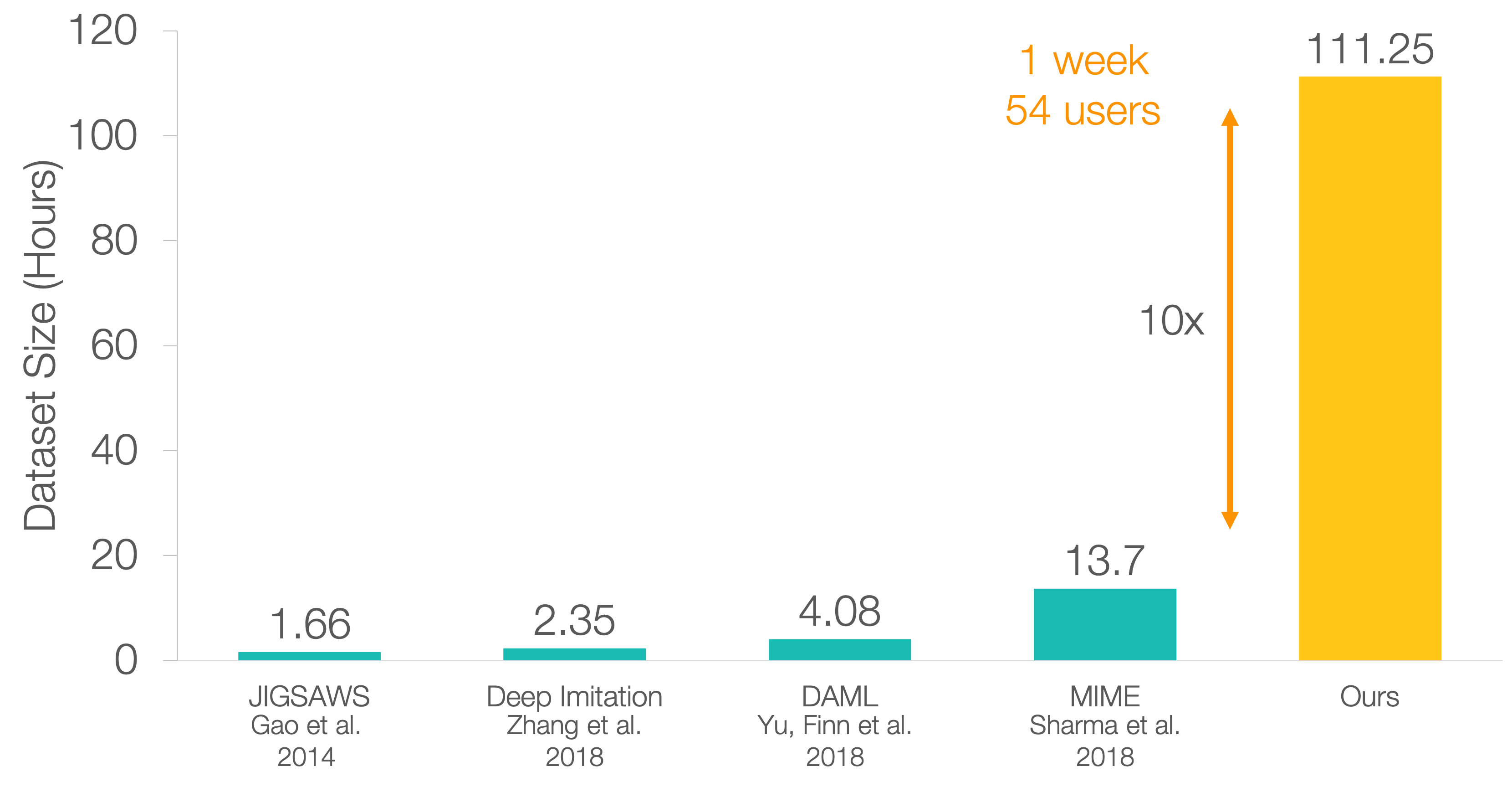

We collected our dataset using 54 different participants over the course of 1 week. Every user participated in a supervised hour of remote data collection, including a brief 5 minute tutorial at the beginning of the session. Afterwards, they were given the option to collect data without supervision for all subsequent collection. The users who participated in our data collection study collected the data from a variety of locations. All locations were remote - no data collection occurred in front of the actual robot arms.

Tasks

We designed three robotic manipulation tasks for data collection, shown above. These tasks were chosen with care in order to make sure that the data collected would be useful for robot generalization. Each task admits diverse solution strategies, which encouraged our diverse set of users to experiment with different solution strategies, requires dexterous manipulation to solve, and the robot needs to learn to generalize to several scenarios. We also note that the tasks would be incredibly difficult to simulate, making physical data collection necessary.

- Object Search. The goal of this task is to search for a set of target objects within a cluttered bin and fit them into a specific box. There are three target object categories: plush animals, plastic water bottles, and paper napkins. A target category is randomly selected and relayed to the operator, who must use the robot arm to find all three objects corresponding to the target category and place each item into its corresponding hole. This task requires precise manipulation due to the bin containing many rigid and deformable objects in clutter, the need to search for hidden objects, and tight object placement.

- Tower Creation. In this task, an assortment of cups and bowls are arranged on the table. The goal of the task is to create the tallest tower possible by stacking the cups and bowls on top of each other. This task requires physical reasoning: operators must use a geometric understanding of objects and dexterous placement to carefully craft their towers while maintaining tower stability.

- Laundry Layout. This task starts with a hand towel, a pair of jeans, or a t-shirt placed on the table. The goal is to use the robot arm to straighten the item so that it lies flat on the table with no folds. On every task reset we randomly place the item into a new configuration. This task requires generalization over several different item configurations.

Data Collection

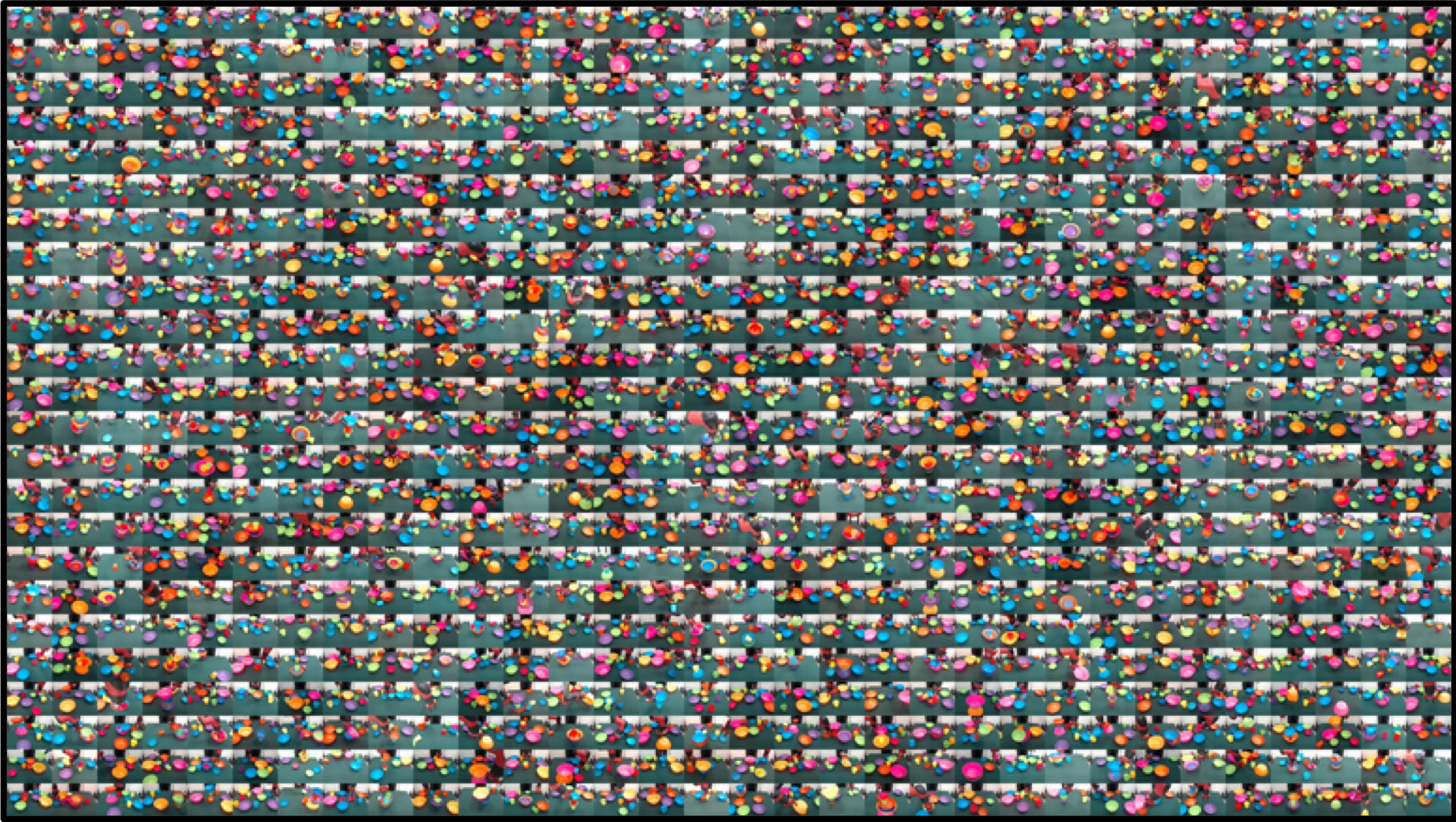

We collected over 111 hours of total robot manipulation data in just 1 week across 54 users on our 3 manipulation tasks, with over 2000 successful demonstrations in total. This makes our dataset 1-2 orders of magnitude larger than most other datasets in terms of interaction time. The number of task demonstrations in our dataset also compares favorably with the number of demonstrations in large datasets such as MIME6, but the tasks that we collected data on are more difficult to complete, as they take on the order of minutes to complete successfully, as opposed to seconds. Some other notable datasets collected by humans include DAML7, Deep Imitation5, and JIGSAWS8.

Here is an assortment of randomly sampled demonstrations from our dataset.

Platform Evaluation

Diverse Solution Strategies

On the Tower Creation task, our users surprised us by building intricate structures out of the simple sets of cups and bowls. We also saw a great deal of diversity in the towers that people chose to build.

Some notable emergent solution strategies that were observed include building an inverted cone and alternating cups and bowls for stability, as well as flipping over a bowl for the base of the tower and grouping 3 cups together to form a stable platform. In particular, we had no idea that it was even possible to control the robot to flip a bowl over - it truly speaks to the power of human creativity coupled with the dexterity that the interface enables.

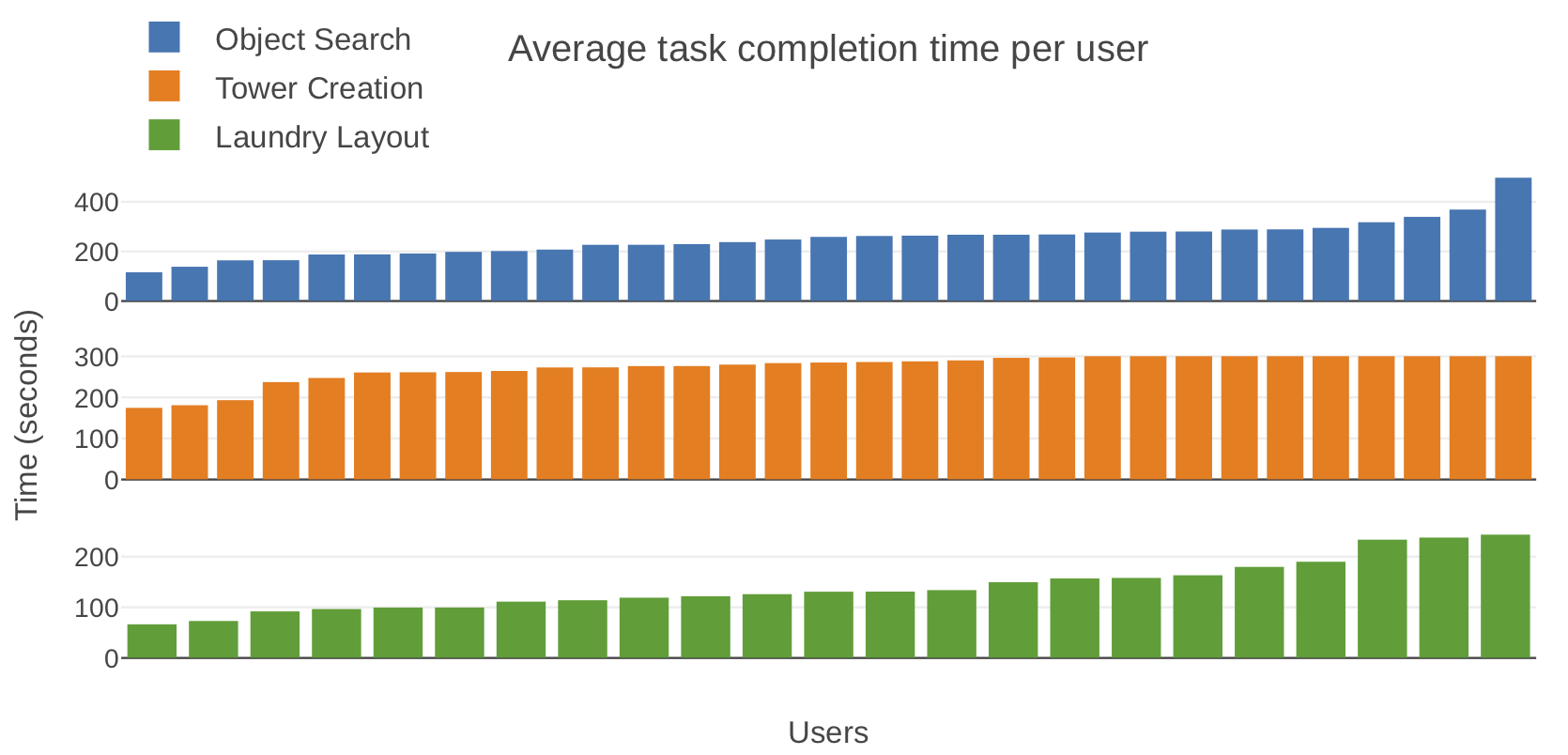

The users themselves were diverse - their skill levels varied significantly. This can be seen from the large variation in average task completion time per user on the Object Search and Laundry Layout tasks in the plot below. User variation naturally emerges from collecting across 54 different people and ensures data diversity. Note that most users were determined to use all 5 of their allotted minutes for the Tower Creation task.

Diverse and Dexterous Manipulation

Next, we present some qualitative examples of diverse and dexterous behaviors in the Object Search task.

In the examples below, the operators used three different strategies to manipulate the plastic water bottle into a favorable place in order to grasp it successfully:

- move to grasp (left): the operator moves the bottle into a convenient position to grasp it

- flip to grasp (middle): the operator flips the water bottle to orient it for a grasp

- approach from angle (right): the operator angles the arm underneath the bottle and the cloth in order to grasp the bottle successfully

In the examples below, the operators decided to extract items from the clutter in order to successfully grasp them.

The examples below show three different strategies we observed for placing target objects into the correct container:

- clever grasp (left): by using a strategic grasp, the operator is able to simply drop the bottle into the container

- stuff (middle): the operator stuffs the napkin into the container

- strategic object use (right): the operator uses one object to poke the other object into the container.

Scaling to New Users

All 54 of our users were new, non-expert users. We found that users with no experience started generating useful data in a matter of minutes.

- On Object Search, new users were able to successfully pick and place a target object for the first time within 2 minutes of interaction time on average.

- On Laundry Layout, new users were able to successfully layout their first towel in less than 4 minutes of interaction on average.

This corroborates the results of our user exit survey - a majority (60.8%) of users reported that they felt comfortable using the system within 15 minutes, while 96% felt comfortable within an hour.

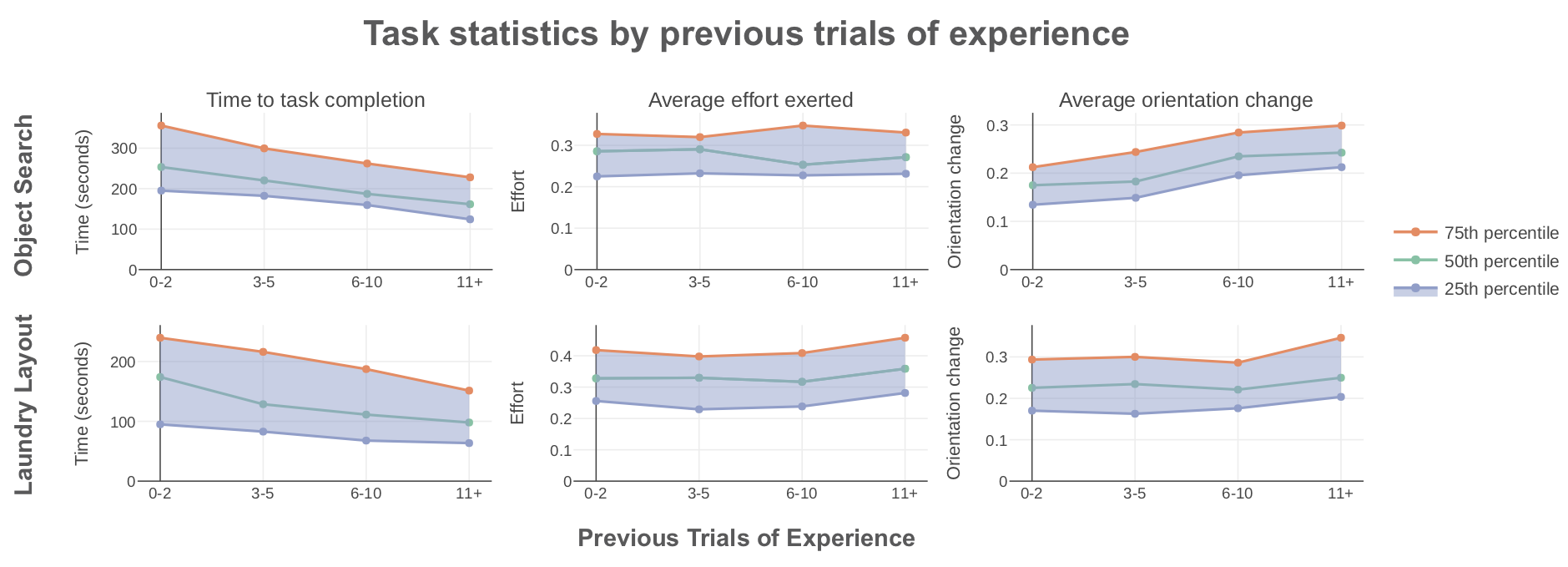

Furthermore, we witnessed significant user improvement over time. As shown below, users learned to complete the task more efficiently over time as they collected more demonstrations. Furthermore, users moved the orientation of the phone more with increasing experience, suggesting that they learned to leverage full 6-DoF control to generate dexterous task solutions of increasing quality.

Leveraging the Dataset

We provide some examples applications for our dataset. However, we emphasize that our dataset can be useful for several other applications as well, such as multimodal density estimation, policy learning, and hierarchical task planning.

Reward Learning

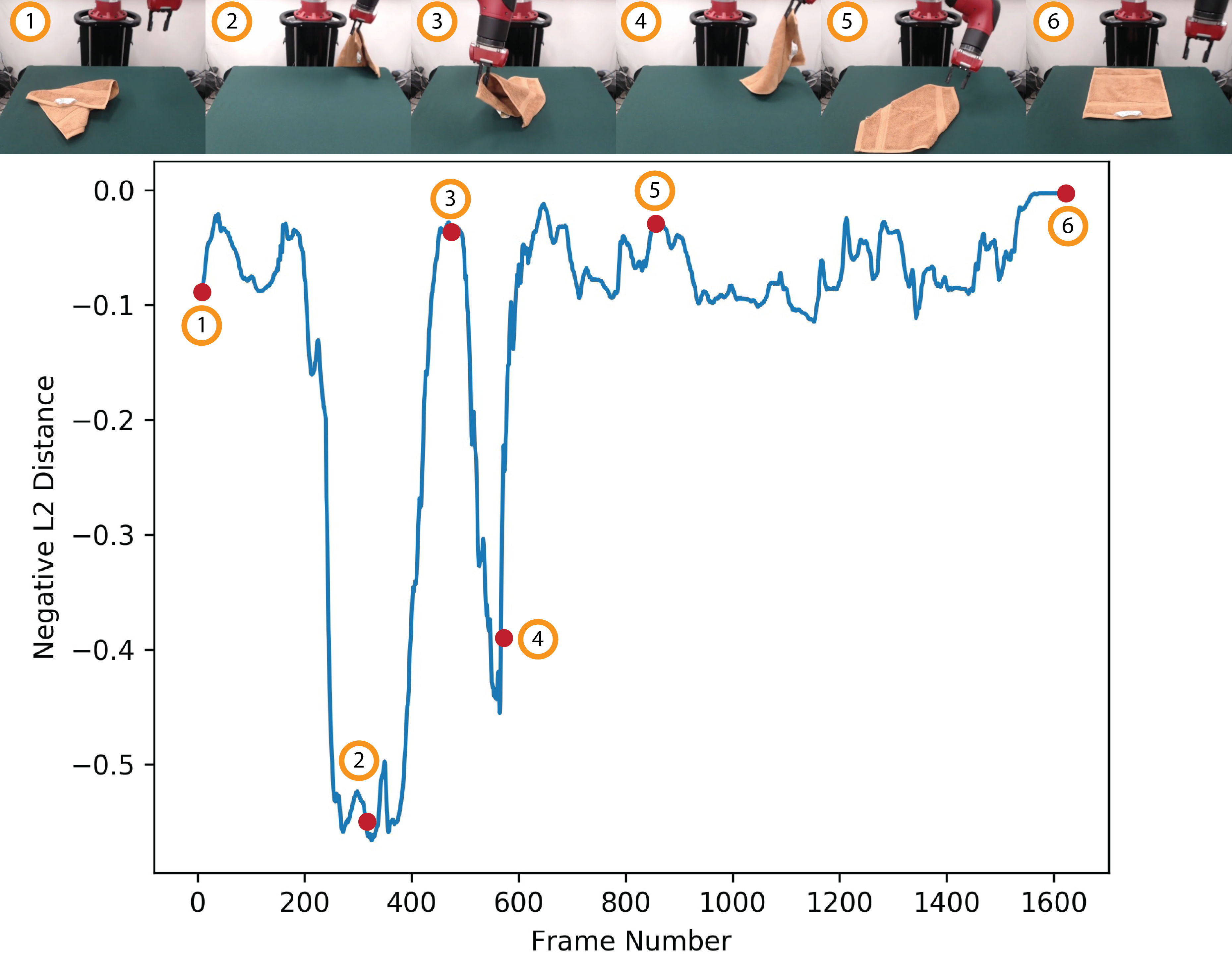

Consider the problem of learning a policy to imitate a specific video demonstration. Prior work has approached this problem by learning an embedding space over visual observations and then crafting a reward function to imitate a reference trajectory based on distances in the embedding space. This reward function can then be used with reinforcement learning to learn a policy that imitates the trajectory. Taking inspiration from this approach, we trained a modified version of Time Contrastive Networks (TCN)9 on Laundry Layout demonstrations and investigate some interesting properties of the embedding space.

In the figure above, we consider the frame embeddings along a single Laundry Layout demonstration. We plot the negative L2 distance of the frame embeddings with respect to the embedding of a target frame near the end of the video, where the target frame depicts a successful task completion with the towel lying flat on the table. The figure demonstrates that distances in this embedding space with a suitable target frame yield a reasonable reward function that could be used to imitate task demonstrations purely from visual observations.

Furthermore, embedding distances capture task semantics to a certain degree and could even be used to measure task progress. For example, in frames 3 and 5, the towel is nearly flat on the table, and the embedding distance to frame 6 is correspondingly small. By contrast, in frames 2 and 4, the robot is holding the towel a significant distance away from the table, and the distance to frame 6 is correspondingly large.

Here is a video that shows how the reward function varies along this demonstration.

Behavioral Cloning

To demonstrate that the data collected by our platform can be used for policy learning, we leveraged a subset of data to train a policy on some Laundry Layout task instances using behavioral cloning. The trained policy is shown below.

Download our datasets!

Our simulation dataset is available on our website and our real robot dataset will be available shortly!

Summary

- RoboTurk is a platform to collect datasets that embody human intelligence. The data contains diverse problem-solving strategies and dexterous object manipulation, and is large-scale.

- We introduce three challenging manipulation tasks: Object Search, Tower Creation, and Laundry Layout. These tasks admit diverse solutions and strategies and require dexterous manipulation to solve. Significant generalization capability is also required for robots to solve these tasks due to the large variation in task instance.

- We present the largest known human teleoperated robot manipulation dataset consisting of over 111 hours of data across 54 users. The dataset was collected in 1 week on 3 Sawyer robot arms using the RoboTurk platform.

- We evalaute our platform and show that the data collected consists of diverse and dexterous task solutions, and that first-time users start generating useful data in minutes and improve significantly over time.

- The dataset has several applications such as multimodal density estimation, video prediction, reward function learning, policy learning and hierarchical task planning, and more.

This blog post is based on the following papers:

-

“RoboTurk: A Crowdsourcing Platform for Robotic Skill Learning through Imitation” by Ajay Mandlekar, Yuke Zhu, Animesh Garg, Jonathan Booher, Max Spero, Albert Tung, Julian Gao, John Emmons, Anchit Gupta, Emre Orbay, Silvio Savarese, and Li Fei-Fei (CORL 2018).

-

“Scaling Robot Supervision to Hundreds of Hours with RoboTurk: Robotic Manipulation Dataset through Human Reasoning and Dexterity” by Ajay Mandlekar, Jonathan Booher, Max Spero, Albert Tung, Anchit Gupta, Yuke Zhu, Animesh Garg, Silvio Savarese, and Li Fei-Fei (IROS 2019).

-

Levine, S., Pastor, P., Krizhevsky, A., & Quillen, D. (2016, October). Learning hand-eye coordination for robotic grasping with large-scale data collection. In International Symposium on Experimental Robotics (pp. 173-184). Springer, Cham. ↩

-

Dasari, S., Ebert, F., Tian, S., Nair, S., Bucher, B., Schmeckpeper, K., … & Finn, C. (2019). RoboNet: Large-Scale Multi-Robot Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.11215. ↩

-

Quillen, D., Jang, E., Nachum, O., Finn, C., Ibarz, J., & Levine, S. (2018, May). Deep reinforcement learning for vision-based robotic grasping: A simulated comparative evaluation of off-policy methods. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 6284-6291). IEEE. ↩

-

Alexandrova, S., Tatlock, Z., & Cakmak, M. (2015, May). RoboFlow: A flow-based visual programming language for mobile manipulation tasks. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 5537-5544). IEEE. ↩

-

Zhang, T., McCarthy, Z., Jow, O., Lee, D., Chen, X., Goldberg, K., & Abbeel, P. (2018, May). Deep imitation learning for complex manipulation tasks from virtual reality teleoperation. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 1-8). IEEE. ↩ ↩2

-

Sharma, P., Mohan, L., Pinto, L., & Gupta, A. (2018). Multiple interactions made easy (mime): Large scale demonstrations data for imitation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.07121. ↩

-

Yu, T., Finn, C., Xie, A., Dasari, S., Zhang, T., Abbeel, P., & Levine, S. (2018). One-shot imitation from observing humans via domain-adaptive meta-learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.01557. ↩

-

Yixin Gao, S. Swaroop Vedula, Carol E. Reiley, Narges Ahmidi, Balakrishnan Varadarajan, Henry C. Lin, Lingling Tao, Luca Zappella, Benjam ́ın B ́ejar, David D. Yuh, Chi Chiung Grace Chen, Ren ́e Vidal, Sanjeev Khudanpur and Gregory D. Hager, The JHU-ISI Gesture and Skill Assessment Working Set (JIGSAWS): A Surgical Activity Dataset for Human Motion Modeling, In Modeling and Monitoring of Computer Assisted Interventions (M2CAI) – MICCAI Workshop, 2014. ↩

-

Sermanet, P., Lynch, C., Chebotar, Y., Hsu, J., Jang, E., Schaal, S., … & Brain, G. (2018, May). Time-contrastive networks: Self-supervised learning from video. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 1134-1141). IEEE. ↩