Around 60 years ago, the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division was established for prohibiting discrimination based on protected attributes. Over these 60 years, they established a set of policies and guidelines to identify and penalize those who discriminate1.

The widespread use of machine learning (ML) models in routine life has prompted researchers to begin studying the extent to which these models are discriminatory. However, some researcher are unaware that the legal system already has well established procedures for describing and proving discrimination in law. In this series of blog posts, we’ll try to bridge this gap. We give a brief overview of the procedures to prove discrimination in law, focusing on employment, and discuss its analogy to discrimination in machine learning. Our goal is to help ML researchers assess discrimination in machine learning more effectively and facilitate the process of auditing algorithms and mitigating discrimination.

This series of blog posts is based on CM-604 Theories of Discrimination (Title VII) and chapters 6 and 7 of TITLE VI Legal Manual. In this first blog post, we discuss the first type of illegal discrimination known as disparate treatment, and in the second blog post, we discuss the second type of illegal discrimination known as disparate impact.

| Machine Learning Analogy |

|---|

| For each section, we give a brief history of related efforts in ML in a green box like this one! |

| Main point |

|---|

| We write the main point for each section in a blue box like this one! |

Table of Contents

- Protected attributes

- Definition of Disparate Treatment

- First step: Establishing a Prima Facie case

- Second step: Rebutting the prima Facie case

- Third step: Proving Pretext

- Real legal cases

Protected Attributes

Anti-discrimination laws are designed to prevent discrimination based on one of the following protected attributes:

- Race – Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Religion – Civil Rights Act of 1964

- National origin – Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Age (40 and over) – Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967

- Sex – Equal Pay Act of 1963 and Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Pregnancy – Pregnancy Discrimination Act

- Familial status – Civil Rights Act of 1968

- Disability status – Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

- Veteran status – Vietnam Era Veterans’ Readjustment Assistance Act of 1974 and Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act

- Genetic information – Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA)

Definition of Disparate Treatment

Disparate treatment occurs when an employer treats some individuals less favorably than other similarly situated individuals because of their protected attributes. “Similarly situated individuals” is specific to each case and cannot be defined precisely, intuitively it means individuals who are situated in a way that it is reasonable to expect that they would receive the same treatment.

During the legal proceddings, the charging party (the party that believes it has suffered from disparate treatment, e.g., employee) accuses the respondent (the party that is accused of treating the charging party less favorably because of their protected attributes, e.g., employer) of disparate treatment.

Although historically, the charging party has to establish that the respondent deliberately discriminated against them, it has been recognized that it is difficult and often impossible to obtain direct evidence of discriminatory motive; therefore, the discriminatory motive can be inferred from the fact of differences in treatment3.

| Disparate Treatment in Machine Learning |

|---|

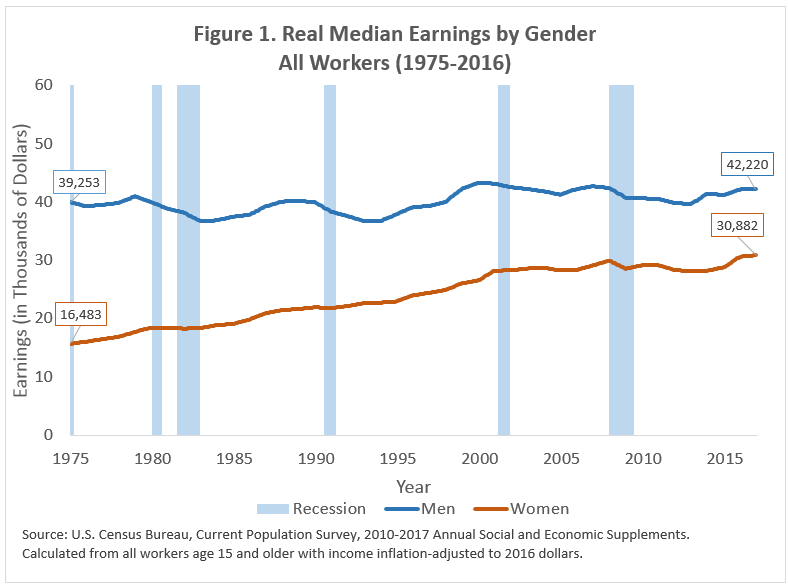

| Humans can have racist, sexist, etc., motives and make decisions based on them, but why would an ML model which does not have any such motives treat similarly situated people differently based on their protected attributes? There are many ways that biases can creep into ML models and cause discrimination (see this short note). As an example, let’s consider distribution bias in data. Due to previous historical discrimination against women, there is a large gap between the average income of men and the average income of women. Although this gap is narrowing over time, it has not been eliminated. Consider a bank that uses an ML model to predict the income of its customers to give them loans accordingly. Consider a very extreme case, where there are no features except the gender of applicants. In this case, it is optimal for the model to rely on the protected gender attribute and predict average income for men if the applicant is a man, and average income for women if the applicant is a woman. Reliance on protected attributes leads to better error in comparison to predicting average income for everyone. Such reliance (and thus disparate treatment) is an optimal strategy for the ML model (see 4 for more details). |

Legal Procedure

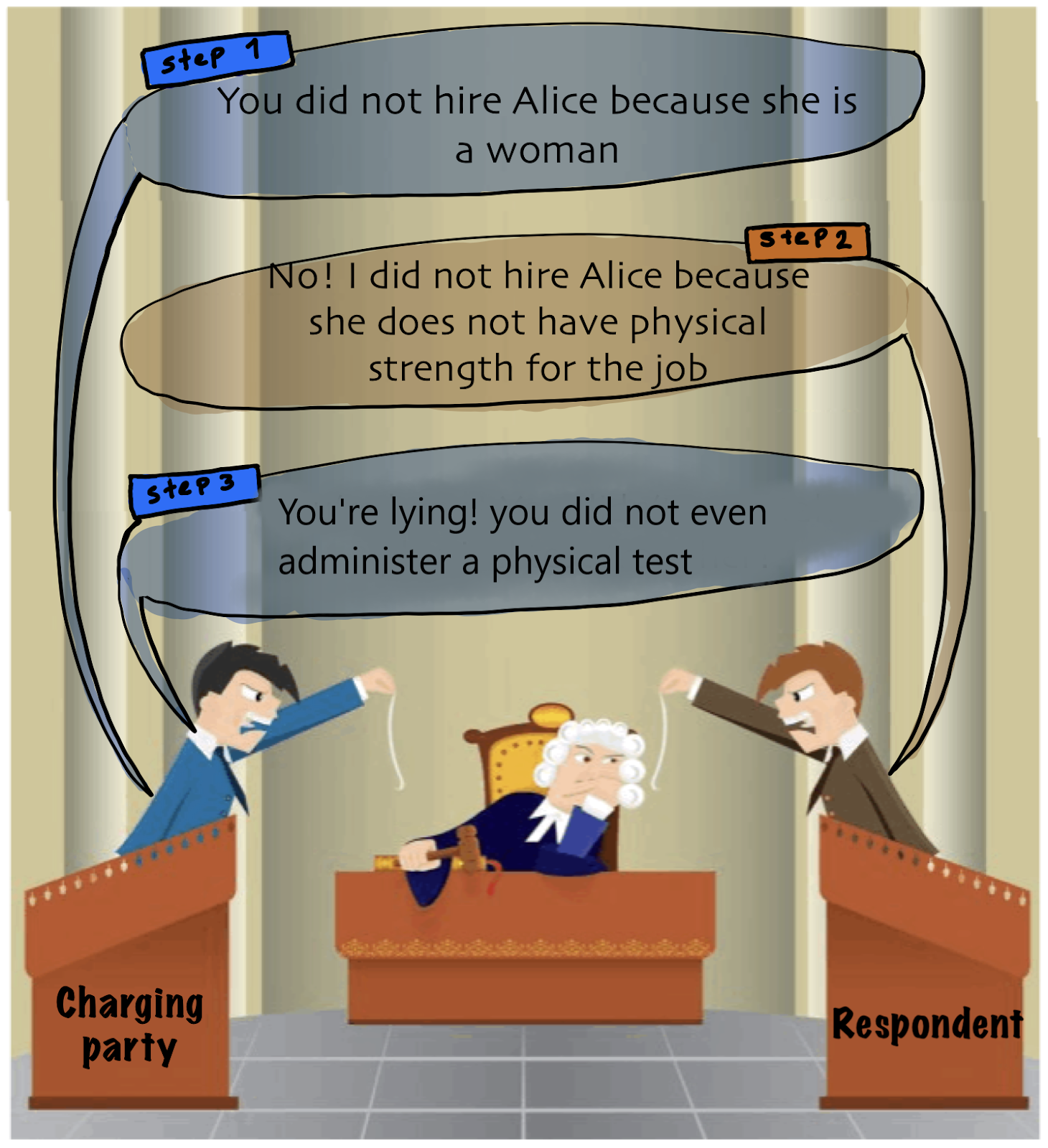

The legal process for proving disparate treatment comprises three steps:

- The charging party must establish a prima facie case of discrimination, i.e., providing enough evidence to support their allegations are true.

- The respondent can rebut the charging party’s case (e.g., providing an alternate explanation for the disparity)

- The charging party can provide evidence that the respondent’s explanations for its actions are pretext, i.e., an attempt to conceal discrimination.

We now expand each step and briefly mention the related work in ML.

| Main Point of Legal Procedure |

| Despite our desire to have an easy definition for discrimination, proving discrimination is a long-term process that involves both sides bringing in reasons and a judge/jury deciding whether there is discrimination or not. |

First step: Establishing a Prima Facie case

Evidence for disparate treatment discrimination can be presented in three main ways:

(a) Comparative Evidence

The disparate treatment theory is based on differences in the treatment of similarly situated individuals. “Similarly situated individuals” cannot be precisely defined, and it is context-dependent. Generally, similarly situated individuals are the ones that are expected to receive the same treatment for a particular employment decision.

For example, when there are some predefined qualifications for promotion, similarly situated individuals are those who meet these qualifications. Or, in the case of discharge (firing), the employer provides a reason for the termination, and people who have committed the same misconduct are similarly situated.

Comparative evidence is a piece of evidence that shows that two similarly situated individuals are treated differently due to their protected attributes.

“For example, an employer’s collective bargaining agreement may contain a rule that any employee charged with theft of company property is automatically discharged. If a Black employee who is charged with theft of company property is discharged, the discharge is consistent with the rule and the agreement. However, the analysis does not end there. To determine whether there was disparate treatment, we should ascertain whether White employees who have been charged with the same offense are also discharged. If they are merely suspended, disparate treatment has occurred. The key to the analysis is that they are similarly situated employees, yet the employer failed to apply the same criteria for discharge to all of them. They are similarly situated because they are respondent’s employees and were charged with the same misconduct. The difference in discipline could be attributable to race, unless respondent produces evidence to the contrary.”5

| ML Efforts on Providing Comparative Evidence |

|---|

| In simple interpretable models we can investigate the features that the model relies upon and find similarly situated individuals 6. For black-box models (e.g., neural nets), there is a lot of research on interpretability to understand model decisions and find similarly situated individuals. In general, models that can provide explanations for their decisions might facilitate the investigation of discrimination. However, if ML models are proprietary then finding similarly situated individuals is challenging. One approach to provide comparative evidence is to define similarly situated individuals as individuals who are only different in their protected attributes or some of their strong proxies and then show that the model’s prediction changes with the protected attribute. For example, 7 show that toxicity detection models give different toxicity scores to the same sentence with different identity terms (e.g., I’m gay vs. I’m straight). 8 show that Google is showing different ads for African American names vs. White names. |

(b) Statistical Evidence

Statistical evidence can also be used to demonstrate discriminatory motives. Charging party uses statistical evidence to prove that the respondent uses protected attributes in its decision9. For example, Alice believes that she is not hired for a secretarial position because she is Black. She can buttress her allegation with statistical evidence indicating that the respondent employs no Black secretaries despite the many applicants in its Metropolitan Statistical Areas. The statistical data shows that the respondent refused to hire Blacks as secretaries; thus, Alice’s rejection was pursuant to this practice. Note that in statistical evidence unlinke the comparative evidence Alice does not need to find a similarly situated individual to herself. It is important to note that statistics alone will not normally prove an individual case of disparate treatment 10.

| ML Efforts on Providing Statistical Evidence |

|---|

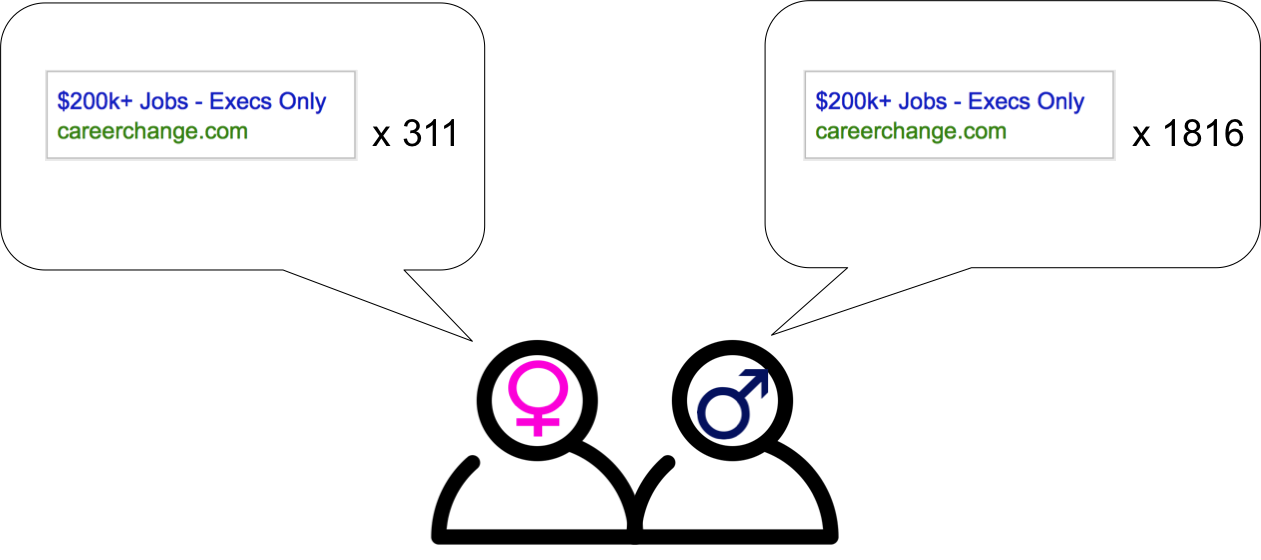

| For generating statistical evidence, a common approach in ML is to generate multiple groups with the same distribution on all features except the protected features and test if the model treats groups differently. For example, 11 show that Google is showing different ads to simulated web browsers with the identical history but different selected genders. A second approach is to control for all potentially relevant risk factors and compare the error rates between groups. The disparity among groups can be evidence of relying on protected attributes. For example, 12 show that there is a performance disparity between pedestrian detection with different skin colors, controlling for time of day and occlusion. So they suggest that these performance disparities could be due to skin color alone, not just due to darker-skinned pedestrians appearing in harder-to-detect scenes13. Studies like 11 illustrate that advertisement models are directly using the gender of a person for ad targeting. This is especially problematic for housing, employment, and credit (“HEC”) ads. Following multiple lawsuits, Facebook agreed on a settlement to apply the following rules when HEC ads. |

| 1) Gender, age, and multicultural affinity targeting options will not be available when creating Facebook ads. |

| 2) HEC ads must have a minimum geographic radius of 15 miles from a specific address or from the center of a city. Targeting by zip code will not be permitted. |

| 3) HEC ads will not have targeting options that describe or appear to be related to personal characteristics or classes protected under anti-discrimination laws. This means that targeting options that may relate to race, color, national origin, ethnicity, gender, age, religion, family status, disability, and sexual orientation, among other protected characteristics or classes, will not be permitted on the HEC portal. |

| 4) Facebook’s “Lookalike Audience” tool, which helps advertisers identify Facebook users who are similar to advertisers’ current customers or marketing lists, will no longer consider gender, age, religious views, zip codes, Facebook Group membership, or other similar categories when creating customized audiences for HEC ads. |

| 5) Advertisers will be asked to create their HEC ads in the HEC portal, and if Facebook detects that an advertiser has tried to create an HEC ad outside of the HEC portal, Facebook will block and re-route the advertiser to the HEC portal with limited options. |

| Google also announced in 202014 that “A new policy will prohibit impacted employment, housing, and credit advertisers from targeting or excluding ads based on gender, age, parental status, marital status, or ZIP Code, in addition to our longstanding policies prohibiting personalization based on sensitive categories like race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, national origin or disability.” Note that even though the advertisers do not target according to the protected attributes, it is still possible that the models use such protected attributes for ad targeting (i.e., models still use protected attributes as a feature for finding the optimal audience for HEC ads). Thus a follow-up study similar to 15 is necessary to make sure that the model does not use gender as a feature for ad targeting. |

| Suggestions on providing statistical evidence |

|---|

| Studies such as 11 are necessary for auditing machine learning models that are deployed. For example, there should be easy ways to investigate if Linkedin (for hiring) is sensitive to protected attributes, or if Twitter or Facebook discriminate in promoting a business page. Such investigation can happen by providing appropriate tools and requiring businesses to be transparent about their methods. |

(c) Direct Evidence of Motive

Direct evidence of motive can be demonstrated by:

- Any statement by the respondent that indicates a bias against members of a protected group

- Showing a failure to take appropriate corrective action in situations where the respondent knew or reasonably should have known that its employees’ practices/policies/behaviors were discriminatory (e.g., not taking action in a sexual harassment case).

| ML efforts on Providing Direct Evidence of Motive |

|---|

| The process of pretraining a model on a large amount of data and then tuning it for a particular purpose is becoming increasingly common in ML. Examples of such models include Resnet pretrained on ImageNet 16 and language models such as BERT 17 and GPT-3 18. There are many works in fairness in ML that show that the word embeddings in language models or features in vision models are misrepresenting 19 20 21 22, or underrepresenting 23 some protected groups. Suppose a company that has knowledge of such biases uses the pretrained BERT model without any constraint as the backbone of its hiring models. In that case, the stereotypical representation of the protected groups can serve as direct evidence of motive 24. |

| Main Point of Step 1: Establishing a Prima Facie Case |

There are three main ways to provide a prima facie case for disparate treatment:

|

Second Step: Rebutting the Prima Facie Case

In the second step, the respondent can bring some evidence to show that the evidence presented by the charging party is not valid. There are six types of rebuttals the respondent can provide:

(a) Charging Party’s Allegations Are Factually Incorrect

(b) Comparison of Similarly Situated Individuals Was Not Valid

This evidence can usually be in the form of (1) Individuals compared are not similarly situated, or the hired individual is more qualified, and (2) Not all similarly situated individuals were compared

(c) Respondent’s Actions were Based on an Act of Favoritism

Title VII only prohibits discrimination based on protected attributes. If in isolated instances a respondent discriminates against the charging party in favor of a relative or friend, no violation of Title VII has occurred.

However, if there are indications that the respondent hired their relative to avoid hiring people from some protected groups, there should be an investigation to determine if the respondent’s actions were a pretext to hide discrimination. In this case, the respondent’s workforce composition and their past hiring practices would be important pieces of evidence.

(d) Charging Party’s Statistical Proof Is Not Meaningful

The respondent can show that statistical proof is not meaningful e.g., it considers the pool of applicants in the state instead of the city.

(e) Statistical Proof To Rebut an Inference of Discriminatory Motive

The respondent can provide statistical data showing that they have not discriminated against protected groups. For example, showing that they have employed a high proportion of a protected group. Even though these kinds of evidence serve as support, they are not conclusive proof that discrimination did not occur. There may not be a pattern and practice of discrimination, but an individual case of disparate treatment may have occurred.

(f) Respondent’s Actions Taken Pursuant to an Affirmative Action Plan

“Affirmative action under the Guidelines is not a type of discrimination but a justification for a policy or practice based on race, sex, or national origin. An affirmative action plan must be designed to break down old patterns of segregation and hierarchy and to overcome the effects of past or present practices, policies, or other barriers to equal employment opportunity. _It must be a concerted, reasoned program rather than one or more isolated events. It should be in effect only as long as necessary to achieve its objectives and should avoid unnecessary restrictions on opportunities for the workforce as a whole. For more details, see the affirmative action manual.”

| ML Efforts on Understanding and Mitigating Disparate Treatment |

|---|

| The ML community has made a lot efforts to understand why a model will rely on protected attributes to either rebut the evidence in step 1 or come up with mitigation methods that guarantee that no discriminatory evidence can be held against them. |

| Understanding why ML models rely on protected attributes: One of the simplest and most frequently studied reasons for such behavior is biased training data. Historically, discrimination was practiced on the basis of protected characteristics (e.g., disenfranchisement of women). These discriminations artificially influenced the distributions of a variety of societal characteristics. Because the data used to train most ML models reflects a world where societal biases exist, the data will almost always exhibit these biases. These biases can be encoded in the labels, such as gender-based pay disparity, or in the features, such as the number of previous arrests when making bail decisions 25. When biased data are used to train ML models, these models frequently encode the same biases. Although learning these biases in ML models, and relying on protected attributes, may achieve low test error, these models can propagate the same injustices that led to the biased data in the first place. Even when protected attributes are explicitly withheld from the model, they remain a confounding variable that influences other characteristics in a way that ML models can pick up on. However, note that training data is not the only reason and biases can creep into the ML cycle at different stages, see this short note. |

| Mitigate disparate treatment: Regarding comparative and statical evidence, ML advocates interpretable models so that it would be easy to argue that the model does not demonstrate disparate treatment 6. In domains such as vision or text, one common approach is to use GAN-style generation and show that the model is invariant to change in protected attributes 26. Regarding the direct evidence of motive, there are many work suggestions fixing word embeddings and predefined features in images and showing their invariance to change in protected attributes 21 27. |

| Main Point of Step 2: Rebutting the Prima Facie Case |

|---|

| As more ways of evaluating ML models are developed, thinking about how they can be connected with their analogues in law would be invaluable. A good practice exercise for a research scientist at a company would be showing that no obvious prima facie case (with any of the three different types of evidence) can be brought against the proposed model. |

Third Step: Proving Pretext

Once the respondent states a legitimate justification for the decision, the charging party can rebut the argument and claim that it’s a pretext for discrimination. For instance, the charging party might present evidence or witnesses that contradict those submitted by the respondent. Or the charging party can show that the respondent gives different justifications at different times for its decision.

| Machine Learning Analogy for Proving Pretext |

|---|

| The first rebuttal against alleged disparate treatment in ML was that they do not use protected attributes as features. Many ML researchers argue that although not using protected attributes and their strong proxies is necessary, it is far from being sufficient. It is easy for machine learning models to predict the protected attributes from other attributes. Therefore, ML models can still be alleged for disparate treatment even when they do not use the protected attributes. In response, counterfactual reasoning has been studied to find “similarly situated” individuals that are treated differently by the algorithm 28 29. However, there are many concerns with counterfactual reasoning with respect to the protected attributes which we summarize here. |

| Immutability of group identity: One cannot argue about the causal effect of a variable if its counterfactual cannot even be defined in principle 30 31. |

| Post-treatment bias: considering the effect of characteristics that are assigned at conception (e.g., race, or sex) while controlling for other variables that follow birth introduces post-treatment bias 32 33. |

| Inferring latent variables: Counterfactual inference needs strong assumptions regarding data generation. |

| Main Point of Step 3: Proving Pretext |

| Only removing protected attributes (and their strong proxy) is not enough! ML models can simply predict protected attributes from other (nonessential) attributes. |

Real Legal Cases34

Age Discrimination

“JPL systemically laid off employees over the age of 40 in favor of retaining younger employees. The complaint also alleges that older employees were passed over for rehire in favor of less qualified, younger employees. Such conduct violates the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA),” according to the EEOC.”

Ramifications: Jet Propulsion Laboratory had to pay $10 million to settle the EEOC age discrimination lawsuit.

Sex Discrimination

“PruittHealth-Raleigh LLC, (PruittHealth) operates a skilled nursing and rehabilitation facility in Raleigh, N.C. Allegedly, PruittHealth subjected Dominque Codrington, a certified nursing assistant, to disparate treatment by refusing to accommodate her pregnancy-related lifting restriction, while accommodating the restrictions of other non-pregnant employees who were injured on the job and who were similar in their ability or inability to work. The EEOC alleged that PruittHealth refused to accommodate Codrington and required her to involuntarily resign in lieu of termination.”

Ramifications: “PruittHealth-Raleigh, LLC paid $25,000 and provide other relief to settle a pregnancy discrimination lawsuit brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The EEOC charged that PruittHealth violated Title VII when it denied a reasonable accommodation to a pregnant employee.”

Race Discrimination

“Koch subjected individual plaintiff/intervenors and classes of Hispanic employees and female employees to a hostile work environment and disparate treatment based on their race/national origin (Hispanic), sex (female), and further retaliated against those who engaged in protected activity. Allegedly, supervisors touched and/or made sexually suggestive comments to female Hispanic employees, hit Hispanic employees and charged many of them money for normal everyday work activities. Further, a class of Hispanic employees was subject to retaliation in the form of discharge and other adverse actions after complaining.”

Ramifications: “Koch Foods, one of the largest poultry suppliers in the world, paid $3,750,000 and furnish other relief to settle a class employment discrimination lawsuit filed by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The EEOC charged the company with sexual harassment, national origin and race discrimination as well as retaliation against a class of Hispanic workers.”

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Alex Tamkin, Jacob Schreiber, Neel Guha, Peter Henderson, Megha Srivastava, and Michael Zhang for their useful feedback on this blog post.

-

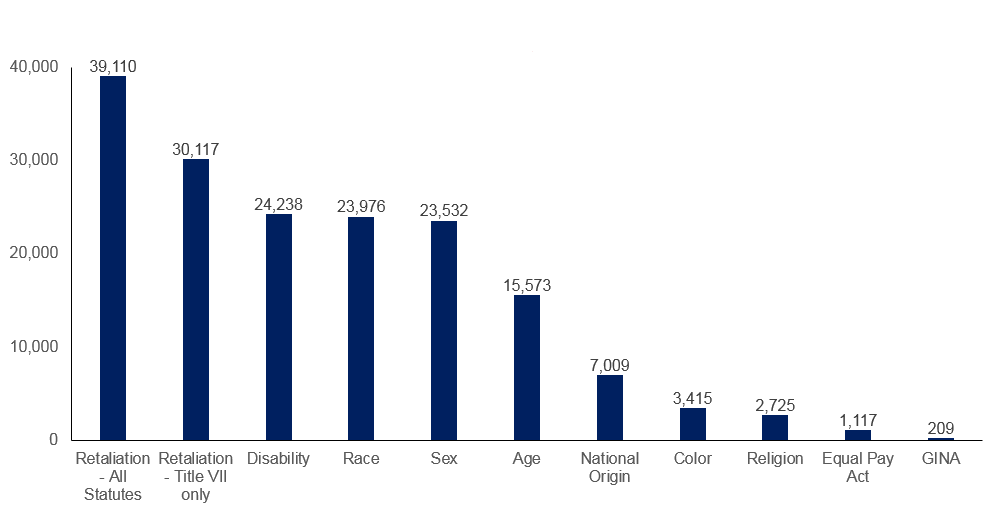

For example, the federal agency that administers and enforces civil rights laws against workplace discrimination charges around 90,000 cases each year, of which around 15% result in monetary benefit (~300 million per year) for the charging party. ↩

-

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/15/us/gay-transgender-workers-supreme-court.html ↩

-

Teamsters, supra; Commission Decision No. 71-1683, CCH EEOC Decisions (1973) ¶ 6262. ↩

-

Khani, Fereshte, and Percy Liang. “Feature noise induces loss discrepancy across groups.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2020. ↩

-

Example from 604.3 (a) of CM-604 Theories of Discrimination ↩

-

Rudin, Cynthia. “Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead.” Nature Machine Intelligence 1.5 (2019): 206-215. ↩ ↩2

-

Garg, Sahaj, et al. “Counterfactual fairness in text classification through robustness.” Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society. 2019. ↩

-

Sweeney, Latanya. “Discrimination in online ad delivery.” Communications of the ACM 56.5 (2013): 44-54. ↩

-

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. U.S., 431 U.S. 324, 14 EPD ¶ 7579 (1977) ↩

-

Bolton v. Murray Envelope Corp., 493 F.2d 191, 7 EPD ¶ 9289 (5th Cir. 1974) ↩

-

Datta, Amit, Michael Carl Tschantz, and Anupam Datta. “Automated experiments on ad privacy settings: A tale of opacity, choice, and discrimination.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1408.6491 (2014). ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Wilson, Benjamin, Judy Hoffman, and Jamie Morgenstern. “Predictive inequity in object detection.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.11097 (2019). ↩

-

Note that, there are many objections to this method as there might be some relevant features that are not reported and not considering them causes false evidence of disparate treatment (see Jung, Jongbin, et al. “Omitted and included variable bias in tests for disparate impact.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.05651 (2018) for more details). ↩

-

Interestingly, while ML researchers have been doing many studies on complicated ways to infer and mitigate discrimination since 2011, up until 2020, HEC advertisers could directly target users with their gender! ↩

-

Datta, Amit, Michael Carl Tschantz, and Anupam Datta. “Automated experiments on ad privacy settings: A tale of opacity, choice, and discrimination.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1408.6491 (2014). ↩

-

He, Kaiming, et al. “Deep residual learning for image recognition.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016. ↩

-

Devlin, Jacob, et al. “Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 (2018). ↩

-

Brown, Tom B., et al. “Language models are few-shot learners.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165 (2020). ↩

-

Bolukbasi, Tolga, et al. “Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? debiasing word embeddings.” Advances in neural information processing systems 29 (2016): 4349-4357. ↩

-

Caliskan, Aylin, Joanna J. Bryson, and Arvind Narayanan. “Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases.” Science 356.6334 (2017): 183-186. ↩

-

Steed, Ryan, and Aylin Caliskan. “Image representations learned with unsupervised pre-training contain human-like biases.” Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 2021. ↩ ↩2

-

Abid, Abubakar, Maheen Farooqi, and James Zou. “Large language models associate Muslims with violence.” Nature Machine Intelligence 3.6 (2021): 461-463. ↩

-

Oliva, Thiago Dias, Dennys Marcelo Antonialli, and Alessandra Gomes. “Fighting hate speech, silencing drag queens? artificial intelligence in content moderation and risks to LGBTQ voices online.” Sexuality & Culture 25.2 (2021): 700-732. ↩

-

This is our analogy of direct evidence of motive to machine learning, and this kind of reasoning has not yet been successfully used in courts. In addition, as we see in the next section, the respondent can rebut such evidence with a protected attribute-neutral explanation (see Hernandez v. New York in which jurors were struck because of their Spanish speaking ability and the explanation was that the prosecutor wanted all jurors to hear the same story from Spanish-speaking witnesses through a translator, not through their own spanish language knowledge) ↩

-

Ramchand, Rajeev, Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, and Martin Y. Iguchi. “Racial differences in marijuana-users’ risk of arrest in the United States.” Drug and alcohol dependence 84.3 (2006): 264-272. ↩

-

Denton, Emily, et al. “Detecting bias with generative counterfactual face attribute augmentation.” arXiv e-prints (2019): arXiv-1906. ↩

-

Bolukbasi, Tolga, et al. “Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? debiasing word embeddings.” Advances in neural information processing systems 29 (2016): 4349-4357. ↩

-

Kusner, Matt J., et al. “Counterfactual fairness.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.06856 (2017). ↩

-

Nabi, Razieh, and Ilya Shpitser. “Fair inference on outcomes.” Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 32. No. 1. 2018. ↩

-

Holland, Paul W. “Statistics and causal inference.” Journal of the American statistical Association 81.396 (1986): 945-960. ↩

-

Freedman, David A. “Graphical models for causation, and the identification problem.” Evaluation Review 28.4 (2004): 267-293. ↩

-

As a simple example, consider the effect of race on the salary of people. We cannot compare the salary of two people of different races at the same job level because race might have led one of them to get mis-leveled. ↩

-

Rosenbaum, Paul R. “The consequences of adjustment for a concomitant variable that has been affected by the treatment.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (General) 147.5 (1984): 656-666. ↩

-

Examples from https://www.digitalhrtech.com/disparate-treatment/ ↩