Seeking human-intelligible explanations

Explaining why a deep learning model makes the predictions it does has emerged as one of the most challenging questions in AI (Lipton 2018, Pearl 2019). There is something of a paradox about this, however. After all, deep learning models are closed, deterministic systems that give us ground-truth knowledge of the causal relationships between all their components. Thus, their behavior is in many ways easy to explain: one can mechanistically walk through the mathematical operations or the associated computer code, and this can be done at varying levels of detail. These are common and valuable modes of explanation in the classroom.

What is missing from these explanations? They don’t provide human-intelligible answers to the actual questions that motivate explanation methods in AI – questions like “Is the model robust to specific kinds of input”, “Does it treat all groups fairly?”, and “Is it safe to deploy?” For explanations that can engage with these questions, we need methods that are provably faithful to the low-level details (Jacovi and Goldberg 2020) but stated in higher-level conceptual terms.

The importance of interventions

Over a series of recent papers (Geiger et al. 2020, Geiger et al. 2021, Geiger et al. 2022, Wu et al. 2022a, Wu et al. 2022b), we have argued that the theory of causal abstraction (Chalupka et al. 2016, Rubinstein et al. 2017, Beckers and Halpern 2019, Beckers et al. 2019) provides a powerful toolkit for achieving the desired kinds of explanation in AI. In causal abstraction, we assess whether a particular high-level (possibly symbolic) mode H is a faithful proxy for a lower-level (in our setting, usually neural) model N in the sense that the causal effects of components in H summarize the causal effects of components of N. In this scenario, N is the AI model that has been deployed to solve a particular task, and H is one’s probably partial, high-level characterization of how the task domain works (or should work). Where this relationship between N and H holds, we say that H is a causal abstraction of N. This means that we can use H to directly engage with high-level questions of robustness, fairness, and safety in deploying N for real-world tasks.

Causal abstraction can be situated within a larger class of explanation methods that are grounded in formal theories of causality. We review a wide range of such methods below. A unifying property of all these approaches is that they involve intervening on model representations to create counterfactual model states and then systematically studying the effects of these interventions on model behavior. This leverages a fundamental insight of causal reasoning: to isolate and characterize causal factors, we need to systematically vary components of our model and study the effects this has on outcomes. In this way, we can try to piece together a complete causal model of the process of interest.

In this post, we review the technical details of causal abstraction in intuitive terms. We focus in particular on the core operation of interchange interventions and seek to relate this operation to interventions employed by other causal explanation methods. Using this idea, we also define interchange intervention accuracy, a new metric that allows us to move beyond simple testing based purely on input–output behavior to directly assess the degree to which a neural model is explained by a high-level model. Finally, we identify some key questions for future work in this area.

Causal abstraction

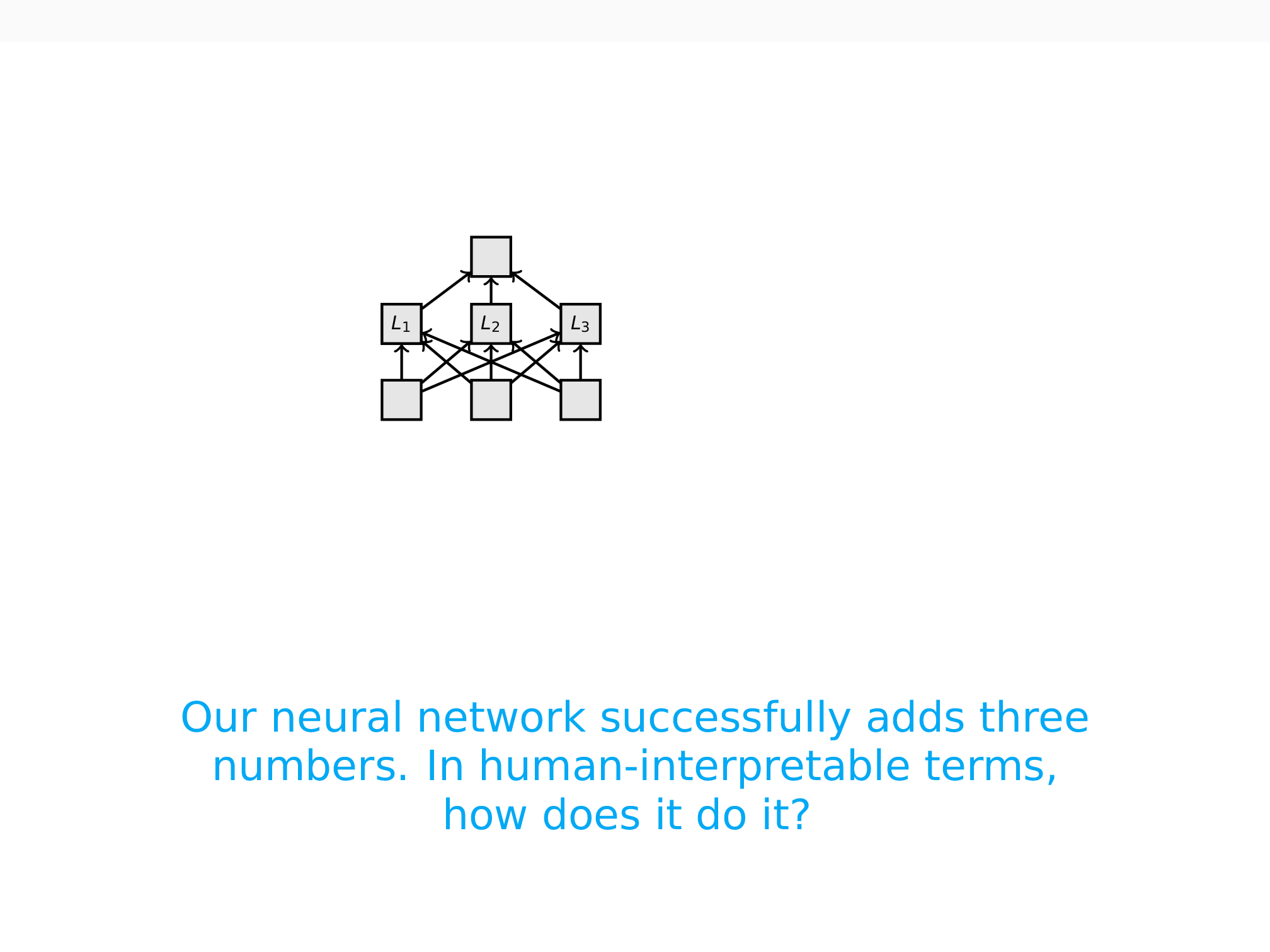

Through the following series of animations, we seek to provide an intuitive overview of how causal abstraction techniques work. The first figure asks you to imagine that you have a neural network that takes in three numbers and adds them together. We can assume that the network does this job perfectly. There is still a further question: How does the network achieve this behavior?

Suppose you formulate the hypothesis that the network (1) adds the first two inputs together to form an intermediate value S1, (2) encodes the value of the third input in a separate internal state w, and (3) uses S1 and w directly to compute the final sum S2. This hypothesis is described by the causal model in green:

Using causal abstraction, we can assess this hypothesis about how our network works. This analysis is based on a series of interchange interventions. The first such intervention happens on the causal model. Using this model, we process the input [1, 3, 5] and obtain the output 9 (purple diagram). Then we use the model to process [4, 5, 6] to get 15 (blue diagram). We also record the intermediate value, S1 = 9, on the way to this result. Finally, we intervene on the first computation by replacing the value of the S1 variable (S1 = 4) with the value we recorded when processing [4, 5, 6] (intervention A). Since the structure of the causal model is fully deterministic and understood, we know that this intervention changes the output to 14.

For the target neural model, the results of intervention are likely to be less clearly known ahead of time, due to the opacity of how these networks map inputs to outputs. Suppose we believe that the hidden state L3 plays the role of S1 in the causal model. To test this, we use the network to get values for inputs [1, 3, 5] and [4, 5, 6] as before. Then we intervene: we take the computed value at L3 from the orange computation and use it in the corresponding place in the yellow computation (intervention B). If this leads the network to output 14, then we have a piece of evidence that the network localizes the S1 variable at L3.

If the causal and neural models agree in this way on all inputs, then we have shown that S1 and L3 are in this aligned relationship. In other words, S1 is a causal abstraction of L3: L3 plays the same causal role in the network that S1 plays in the high-level algorithm.

We can perform the same kind of interchange interventions to assess whether L1 plays the role of w. The technique could also lead us to discover that the state L2 plays no causal role in the network’s behavior, if interventions on that value never affect the model’s input–output behavior. In this way, interchange interventions reveal to us the causal structure of the neural model. If we can successfully align all of the variables in the high-level model with variables (or sets of them) in the low-level model, then we say that the high-level model is a causal abstraction of the low-level model (under our chosen alignment).

This is a simple illustrative example, but the techniques apply to complex, large-scale problems as well. Geiger et al. (2020) employed an early version of causal abstraction analysis to explain why Transformer-based models achieve robust compositional generalization for natural language inference (NLI) examples involving lexical entailment and negation. Geiger et al. (2021) and Geiger et al. (2022) subsequently developed the theoretical foundations for this kind of analysis, building on Beckers and Halpern’s (2019) proposals, and applied the method to more complex NLI examples with quantifiers, negation, and modifiers, as well as to problems in computer vision and grounded language use. Li, Nye, and Andreas (2021) employed this method to find implicit semantic representations in language models.

Interchange intervention training

A clear limitation of the above methods is that we needed to figure out which alignment hypotheses to test. If we test the wrong ones, we might fail to identify the causal structure that is actually present. For current deep learning models, the number of representations to check might be very large, and the tenets of causal abstraction allow us to test alignments involving subparts of these representations as well as sets of representations. This leads to an astronomically large set of alignment hypotheses to test. We may be able to rule out some of these hypotheses in principle, but there will still be many, many plausible ones.

In practice, we have sought to address this by using probe models (e.g., Tenney et al. 2019) and feature attribution methods (e.g, Sudararajan et al. 2017) to heuristically find alignments that are likely to be good given our high-level models. For example, in our simple addition network, feature attribution methods might tell us that L2 makes no contribution to the model’s predictions, and thus we could eliminate L2 as a candidate for playing the role of S1 or w in the causal model. Furthermore, supervised probes might allow us to home in on L3 as the most likely counterpart of the S1 variable. These techniques are especially important where one is testing hypotheses about a very large model that can’t be changed, but rather must be studied and understood in its own right.

In many situations, though, we have the freedom to move out of this pure analysis mode and can instead actually train networks to have the causal structure that we hope to see. We call this interchange intervention training (IIT; Geiger et al. 2022,Wu et al. 2022). With IIT, we push the neural model to conform to the causal model while still allowing it to learn from data as usual. IIT is a very intuitive extension of causal abstraction: our interventions create “Frankenstein” back-propagation graphs that combine the graphs from other examples. This creates new training instances that we can label with our causal model:

For our running example, this means that we train the network not only to handle inputs like [1, 3, 5] properly, but also to make correct predictions under the intervention storing 4 + 5 at L3. Comparable interventions could support the alignment of w and L1. The result is a neural model that is not only successful at our task but corresponds to the causal dynamics of the high-level model. For complex tasks grounded in real data, this will combine the benefits of standard data-driven learning with the structure provided by the high-level model.

Beyond simple behavioral evaluation: Interchange Intervention Accuracy

Throughout AI, we rely on behavioral evaluations to determine how successful our models are. For example, classifier models are assessed by their ability to accurately predict the labels for held-out test examples, and language models are assessed by their ability to assign high probability to held-out test strings. Such evaluations can be highly informative, but their limitations immediately become evident when we start to think about deploying models into unfamiliar contexts where their inputs are likely to be different from those they were evaluated on. In such contexts, their behavior might be unsystematic, or systematically biased in problematic ways.

Interchange interventions can be used to define more stringent evaluation criteria. Our primary metric in this space is interchange intervention accuracy, which assesses how accurate the model is under the counterfactuals created by interchange interventions of a particular kind. Such evaluations directly assess how close the target model comes to realizing a specific high-level causal model.

As Geiger et al. (2022) show, models can have perfect behavioral accuracy but imperfect interchange intervention accuracy. Such models have found good solutions that are nonetheless unsystematic with respect to the high-level causal model. If it is vital that we conform to the causal model, due to reasons related to safety or fairness, then we have diagnosed a pressing problem that was hidden by standard behavioral testing.

Other intervention-based methods as a special case of causal abstraction

Causal abstraction is a general framework for explanation methods in AI. The basic operation is the intervention, which we can express using notation from Pearl (2009): MY←y is the model that is identical to M except the values for the variables Y are set to the constant values y. The nature of this intervention is left wide open, and different choices give us different methods. Many popular behavioral and intervention-based explanation methods in AI can be explicitly understood as a special case of causal abstraction. A number of prominent examples are described in our appendix.

Ongoing work

The methods explored above are in their infancy, especially with respect to explainability applications in AI. To close this post, let’s chart out a few exciting open avenues for research:

Benchmarking explanation methods

CEBaB (Abraham et al. 2022) is a naturalistic benchmark for making apples-to-apples comparisons between explanation methods. Upon its release, existing methods generally did not perform better than simple baselines. In Wu et al. 2022b, we use intervention-based methods to develop Causal Proxy Models (CPMs). Input-based CPMs use simple interventions on inputs, whereas hidden-state CPMs use IIT to localize concepts in specific internal representations. Both kinds of CPM achieve state-of-the-art results on CEBaB. In addition, they achieve strong task performance, which suggests that they can actually be deployed as more explainable variants of the models they were initially intended to explain.

Model distillation

Wu et al. (2022) augment the standard language model distillation objectives (Sanh et al. 2019) with an IIT objective and show that it improves over standard distillation techniques in language model perplexity (Wikipedia), the GLUE Benchmark, and the CoNLL-2003 named-entity recognition task. These preliminary results show that IIT has great promise for distillation. This has inherent value and also begins to show us how general and abstract the causal models for IIT can be; in our earlier use-cases, it is a symbolic model, whereas here it is essentially just an alignment between the hidden representations in two neural models.

Theoretical foundations

We are seeking to further develop the core theory of causal abstraction so that we can confidently apply the methods to a wider range of models and unify existing approaches rigorously.

A rallying cry

AI models are at work all around us, in diverse contexts serving diverse goals. The prevalence of these models in our lives tracks directly with their increasing size and deepening opacity. Explanation methods are a crucial part of making sure these deployments go as expected. Causal abstraction analysis supports a family of causal methods that seem to be our best bet at achieving explanations that are both human-interpretable and true to the actual underlying causal structure of these models. We hope that centering the discussion around interventions and abstraction helps point the way to new and even more powerful methods.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to SAIL editors Jacob Schreiber and Megha Srivastava for extremely valuable input.

Appendix: Details on other intervention-based methods

We noted above that a number of explanation methods in AI can be described using tools and techniques from causal abstraction. Here we provide some examples with references.

- Explanation methods purely grounded in the behavior of a model can be directly interpreted in causal terms when we interpret the act of providing an input to a model as an intervention to the input variable. Methods like LIME (Ribeiro et al. 2016), ConceptSHAP (Yeh et al. 2020), and estimating the causal effect of real-world concepts on model behavior only consider input–output behavior, so causal abstraction can accurately capture these simple methods using two-variable (input and output) causal models.

- Input manipulations and data augmentation methods generally correspond to interventions on model inputs (Molnar 2022). Many feature attribution methods can be stated in these terms. For example, deleting a feature Y in model M corresponds to the intervention MY←0. In permutation-based feature importance, we randomly shuffle the value of a feature. This can be seen as a series of random interventions on inputs. Begus (2020) uses input interventions to argue that unsupervised deep speech networks learn to represent phonemes. All these methods also can be seen as causal abstraction analysis with a two-variable chain.

- Interventions could even happen at the level of the data-generating process (Feder et al. 2021, Abraham et al. 2022) or model training data statistics (Elazar et al. 2022). Causal abstraction represents these methods as marginalizing away every variable other than the real-world concept of interest and the model output.

- Causal mediation analysis (Vig et al. 2020, Meng et al. 2022) is an early and influential use of interventions to explain models. In this mode, we study the ways in which a model’s input–output relationships are mediated by intermediate variables, and we do this by intervening on those intermediate variables to identify direct and indirect causal effects. This can be understood as causal abstraction analysis with a three-variable chain for the high-level model.

- In Iterative Nullspace Projection, we project the original vector onto the null space of a linear probe (Ravfogel et al. 2021, Elazar et al. 2021). This can also be modeled as abstraction by a three-variable causal model.

- Circuit-based explanations (Cammarata et al. 2020) contend that neural networks consist of meaningful, understandable features connected in circuits formed by weights. Causal abstraction analysis can be directly applied to operationalize such questions.

- When interventions target neural vector representations, the values of the intervention y might be zero vectors, a perturbed or jittered version of the original vector, a learned binary mask applied to the original vector (Csordás, Steenkiste, and Schmidhuber 2021, De Cao et al. 2021), or a tensor product representation (Soulos et al. 2020). Interchange interventions are a special case of this where the values y are values realized by the representation on some other actual input.

References

Abraham, Eldar David, Karel D’Oosterlinck, Amir Feder, Yair Ori Gat, Atticus Geiger, Christopher Potts, Roi Reichart, and Zhengxuan Wu. 2022. CEBaB: Estimating the causal effects of real-world concepts on NLP model behavior. To appear in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

Beckers, Sander, Frederick Eberhardt, and Joseph Y. Halpern. 2019. Approximate causal abstractions. In Proceedings of the 35th Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence Conference, 606–615.

Beckers, Sander, and Joseph Halpern. 2019. Abstracting causal models. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

Beguš, Gašper. 2020. Generative adversarial phonology: Modeling unsupervised phonetic and phonological learning with neural networks. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 3.

Cammarata, Nick, Shan Carter, Gabriel Goh, Chris Olah, Michael Petrov, Ludwig Schubert, Chelsea Voss, Ben Egan, and Swee Kiat Lee. 2020. Thread: Circuits. Distill.

Chalupka, Krzysztof, Frederick Eberhardt, and Pietro Perona. 2016. Multi-level cause-effect systems. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, 361–369, Cadiz, Spain.

Chattopadhyay, Aditya, Piyushi Manupriya, Anirban Sarkar, and Vineeth N Balasubramanian. 2019. Neural network attributions: A causal perspective. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning.

Csordás, Róbert, Sjoerd van Steenkiste, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. 2021. Are neural nets modular? Inspecting functional modularity through differentiable weight masks. In 9th International Conference on Learning Representations.

De Cao, Nicola, Leon Schmid, Dieuwke Hupkes, and Ivan Titov. 2021. Sparse interventions in language models with differentiable masking. arXiv:2112.06837.

Elazar, Yanai, Nora Kassner, Shauli Ravfogel, Amir Feder, Abhilasha Ravichander, Marius Mosbach, Yonatan Belinkov, Hinrich Schütze, and Yoav Goldberg. 2022. Measuring causal effects of data statistics on language model’s ‘factual’ predictions. arXiv.2207.14251.

Elazar, Yanai, Shauli Ravfogel, Alon Jacovi, and Yoav Goldberg. 2021. Amnesic probing: Behavioral explanation with amnesic counterfactuals. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 9: 160–75.

Feder, Amir, Nadav Oved, Uri Shalit, and Roi Reichart. 2021. CausaLM: Causal model explanation through counterfactual language models. Computational Linguistics 47: 333–386.

Geiger, Atticus, Ignacio Cases, Lauri Karttunen, and Christopher Potts. 2019. Posing fair generalization tasks for natural language inference. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, 4475–85. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Geiger, Atticus, Hanson Lu, Thomas F. Icard, and Christopher Potts. 2021. Causal abstractions of neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 9574–9586.

Geiger, Atticus, Kyle Richardson, and Christopher Potts. 2020. Neural natural language inference models partially embed theories of lexical entailment and negation. In Proceedings of the Third BlackboxNLP Workshop on Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Geiger, Atticus, Zhengxuan Wu, Hanson Lu, Josh Rozner, Elisa Kreiss, Thomas Icard, Noah Goodman, and Christopher Potts. 2022. Inducing causal structure for interpretable neural networks In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, 7324–7338.

Jacovi, Alon, and Yoav Goldberg. 2020. Towards faithfully interpretable NLP systems: How should we define and evaluate faithfulness? In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 4198–4205. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Li, Belinda Z., Maxwell I. Nye, and Jacob Andreas. 2021. Implicit representations of meaning in neural language models In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, 1813–1827. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Lipton, Zachary C. 2018. The mythos of model interpretability. Communications of the ACM 10: 36–43.

Meng, Kevin, David Bau, Alex Andonian, and Yonatan Belinkov. 2022. Locating and editing factual associations in GPT, arXiv:2202.05262.

Molnar, Christoph. 2020. Interpretable machine learning: A guide for making black box models explainable.

Pearl, Judea. 2009. Causality. Cambridge University Press.

Pearl, Judea. 2019. The limitations of opaque learning machines. In John Brockman, ed., Possible Minds: Twenty-Five Ways of Looking at AI, 13–19.

Ravfogel, Shauli, Grusha Prasad, Tal Linzen, and Yoav Goldberg. 2021. Counterfactual interventions reveal the causal effect of relative clause representations on agreement prediction. In Proceedings of the 25th Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, 194–209. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Ribeiro, Marco Tulio, Sameer Singh, and Carlos Guestrin. 2016. “Why Should I Trust You?: Explaining the predictions of any classifier In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining.

Rubenstein, Paul K., Sebastian Weichwald, Stephan Bongers, Joris M. Mooij, Dominik Janzing, Moritz Grosse-Wentrup, and Bernhard Schölkopf. 2017. Causal consistency of structural equation models. In Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence. Association for Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence.

Sanh, Victor, Lysandre Debut, Julien Chaumond, and Thomas Wolf. 2019. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv:1910.01108.

Soulos, Paul, R. Thomas McCoy, Tal Linzen, and Paul Smolensky. 2020. Discovering the compositional structure of vector representations with role learning networks. In Proceedings of the Third BlackboxNLP Workshop on Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, 238–254. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Sundararajan, Mukund, Ankur Taly, and Qiqi Yan. 2017. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning 70, 3319–3328.

Tenney, Ian, Dipanjan Das, and Ellie Pavlick. 2019. BERT rediscovers the classical NLP pipeline. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 4593–4601.

Vig, Jesse, Sebastian Gehrmann, Yonatan Belinkov, Sharon Qian, Daniel Nevo, Yaron Singer, and Stuart Shieber. 2020. Causal mediation analysis for interpreting neural NLP: The case of gender bias. arXiv:2004.12265.

Wu, Zhengxuan, Atticus Geiger, Joshua Rozner, Elisa Kreiss, Hanson Lu, Thomas Icard, Christopher Potts, and Noah Goodman. 2022a. Causal distillation for language models. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 4288–4295. Association for Computational Linguistics.

Wu, Zhengxuan;* Karel D'Oosterlinck;* Atticus Geiger;* Amir Zur; and Christopher Potts; 2022b. Causal Proxy Models for concept-based model explanations. arXiv: 2209.14279.

Yeh, Chih-Kuan, Been Kim, Sercan Arik, Chun-Liang Li, Tomas Pfister, and Pradeep Ravikumar. 2020. On completeness-aware concept-based explanations in deep neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33:20554–20565.