TL;DR - It is not unusual that AI benchmarks contain flawed questions and are improperly graded, which undermines evaluation reliability. We introduce a framework that draws on measurement-theoretic methods, using response-pattern statistics to flag anomalous questions for review. In addition, we introduce an LLM‑judge first pass to review questions, further reducing the review effort required from human experts. Across nine widely used benchmarks, our framework guides human experts to identify flawed questions with up to 84% precision@k, providing an efficient and scalable framework for systematic benchmark revision. [Paper][GitHub][Data]

Introduction

NLP benchmarks drive progress in large language models (LLMs). Unfortunately, prior research has shown that GSM8K, a widely used grade school math benchmark, has an error rate as high as 5%—a total of 88 questions. Such flawed questions can distort model rankings and undermine evaluation reliability. Before revision, DeepSeek-R1 ranked near the bottom (third lowest) on GSM8K, whereas after revision, it rose to become one of the top-performing models, achieving second place. A reliable measurement requires systematic benchmark revision.

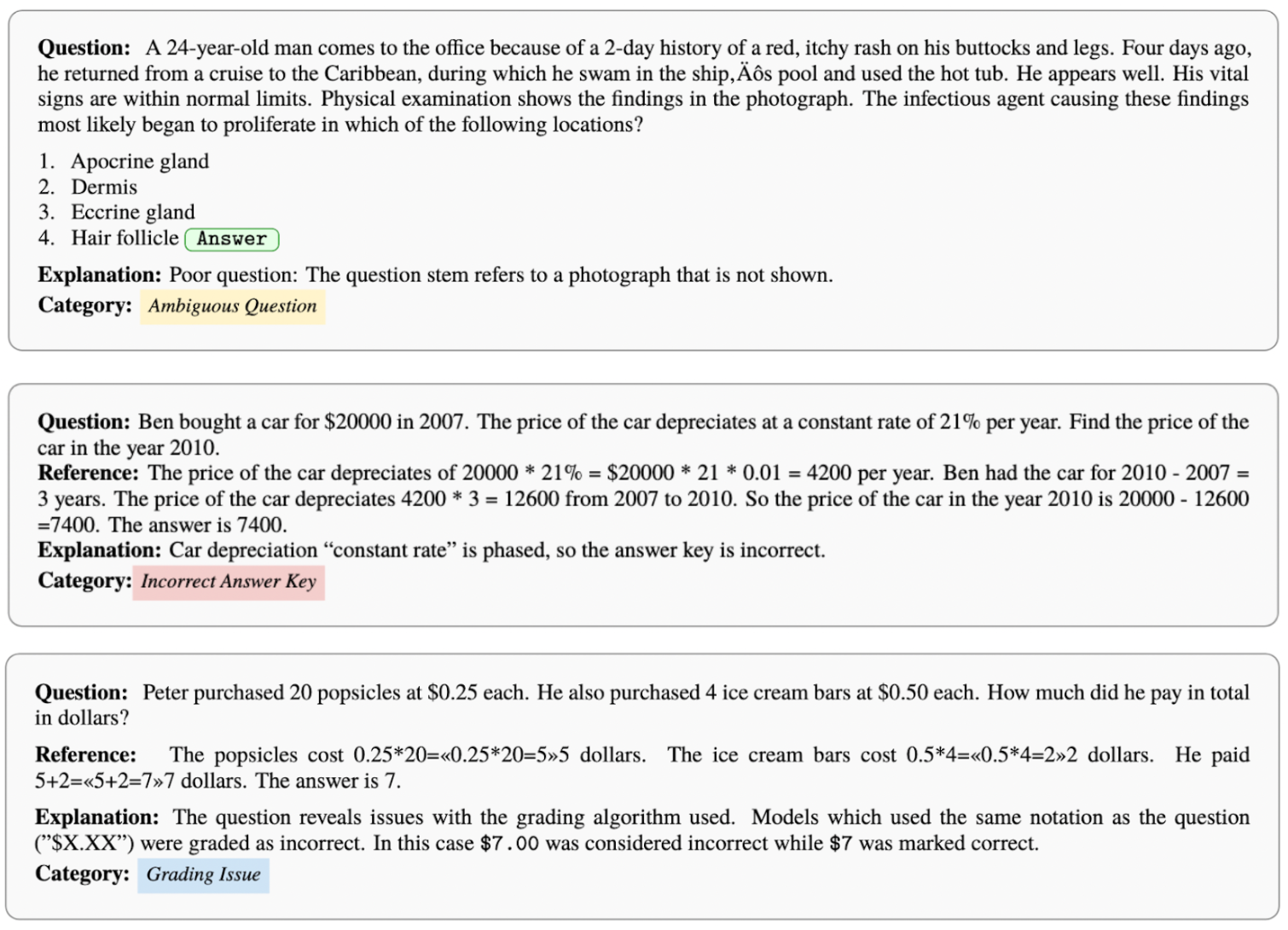

We identify three main categories of flawed benchmark questions: ambiguous questions, incorrect answer keys, and grading issues. We illustrate an example of each category in Figure 1. An ambiguous question arises when the phrasing allows multiple valid interpretations, yet the answer key provides only a single correct answer. An incorrect answer key refers to errors in the reference key itself. A grading issue stems from limitations in the automated scoring system’s NLP component. For example, if the correct answer is “$4.00” but the grader only accepts “4”, the system may incorrectly mark an LLM’s response as wrong simply because it retains the decimal places—an error caused by the grader rather than the question or key.

Manually identifying flawed questions in modern AI benchmarks is prohibitively expensive. These benchmarks often contain thousands of questions across diverse domains, each requiring specialized expertise to verify correctness. For example, MMLU spans 57 domains ranging from chemistry to philosophy and contains over 14,000 questions. The problem is even more pronounced with grading issues, which require reviewers to examine LLM responses rather than just reviewing questions and answer keys. As a result, most benchmarks are rarely revised after release, underscoring the need for methods that assist human reviewers by automatically flagging potentially flawed questions.

To address this challenge, we draw on measurement-theoretic methods, employing statistical signals—inter-item correlation, scalability coefficient, and item–total correlation—to flag anomalous questions based on response patterns. We also introduce an LLM‑judge first pass to review questions, which is particularly efficient for detecting grading issues. Both components are described in detail in the following methods section.

Method

We collect a binary response matrix of LLMs' answers to the benchmark questions, where each entry is 1 if the answer is correct and 0 otherwise. From this matrix, we can directly compute the statistical signals. We provide an intuitive explanation for each metric. Inter-item correlation (e.g., inter-item tetrachoric correlation and scalability coefficient) measures how likely LLMs that answer one question correctly will answer another correctly. Item–total correlation captures how well performance on a single question aligns with overall test performance. For the rigorous mathematical definitions of these statistical signals, please refer to our paper.

Many AI benchmarks report an average score. If we assume this score as a stable measure of performance, it is reasonable to assume further that it is a sufficient statistic for the measurement target. Under mild additional assumptions, such as conditional independence of item responses given ability, we can derive expected ranges for statistics: all item–item correlations should be nonnegative, and items should correlate positively with the total score. As a result, questions with statistics falling outside these ranges are flagged as potentially flawed. For a rigorous proof, see our paper.

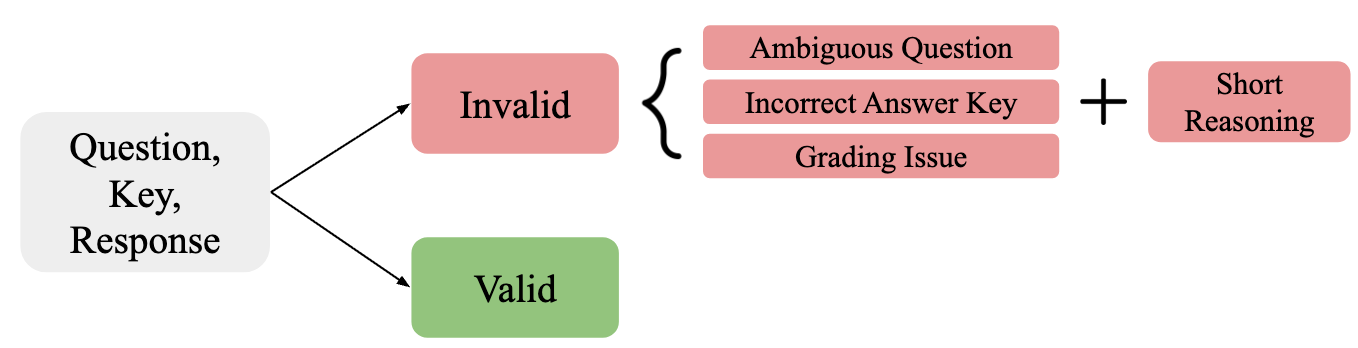

Next, we describe the LLM-judge first pass. We submit to a frontier LLM along with (a) the question prompt, (b) the official answer key, and (c) several exemplar LLM responses. The LLM-judge is instructed to classify the question as either valid or invalid. If it deems the question invalid, it further assigns one of three predefined invalid categories and provides a concise justification, as shown in Figure 2. Human experts then review these judgments. This process is particularly helpful for grading issues, which require significant additional effort to verify manually. Leveraging the LLM-judge’s NLP capabilities to assess whether a response is semantically equivalent to the answer key can reveal shortcomings in the automated grading system. Additionally, if the inspected benchmark is saturated—i.e., frontier LLMs achieve near-perfect scores—the LLM-judge can effectively identify ambiguous questions and incorrect answer keys.

Results

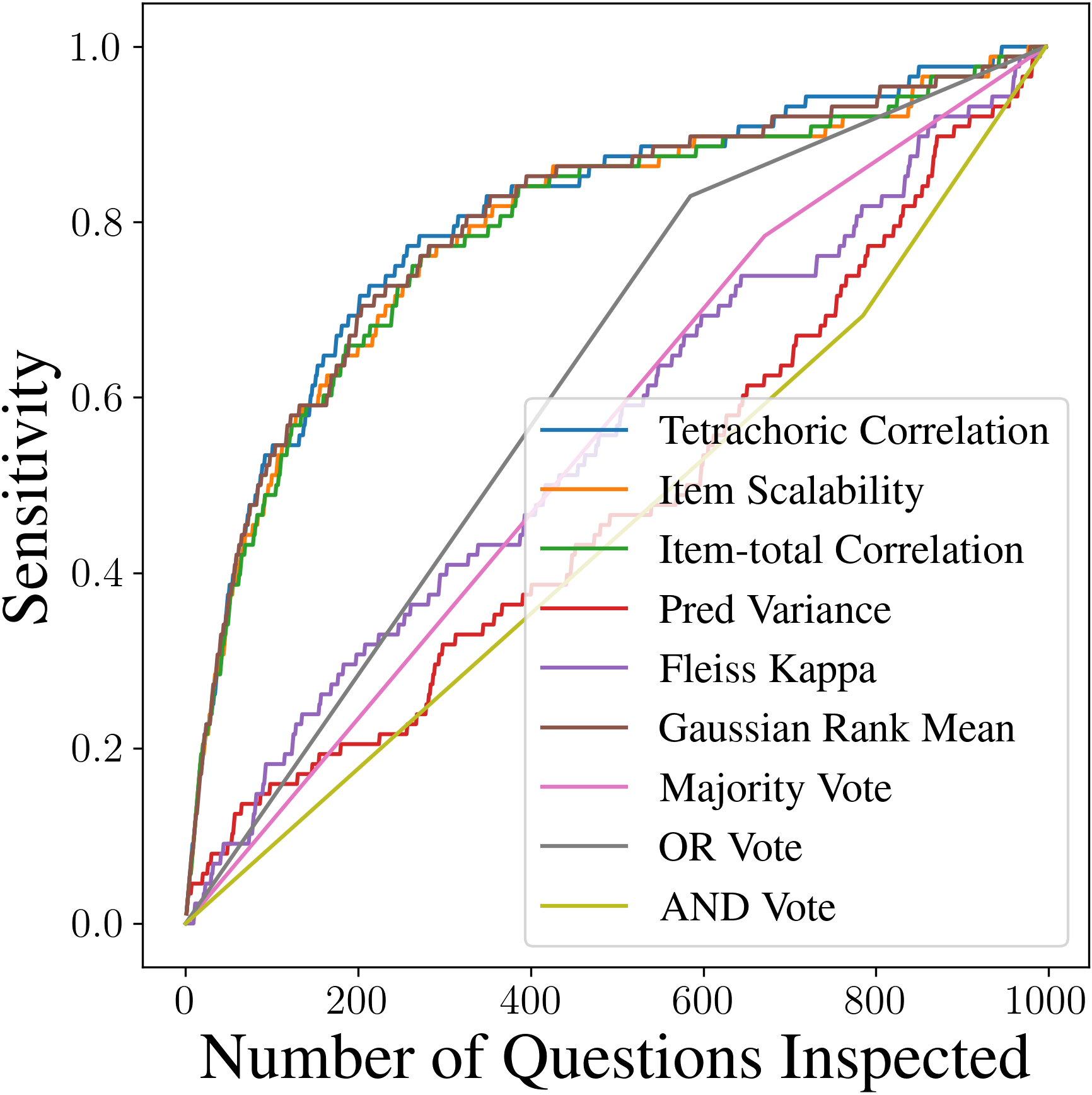

We first show that the three measurement-theoretic methods we use outperform naive baselines and that no single method uncovers all invalid questions. We analyze GSM8K, a dataset with human annotations identifying 88 invalid questions out of 997 total. Responses from LLMs are collected via the HELM leaderboard and organized into binary response matrices. We evaluate our three methods, two heuristic baselines variance in predictions, a method adopted in prior work and Fleiss’ Kappa and four ensemble methods (average Gaussian-rank, AND Vote, OR Vote, and Majority Vote). To measure detection performance, we compute Sensitivity, defined as Sensitivity(k) = TP(k)/R, where TP(k) denotes the number of invalid questions identified among the top k questions and R denotes the total number of invalid questions. As shown in Figure 3, our methods achieve substantially higher sensitivity than baselines. However, while individual methods detect many errors at shallow inspection depths, their performance plateaus quickly. From the binary vote results, we can further conclude that they detect different sets of invalid questions. This is consistent with the No Free Lunch (NFL) principle in anomaly detection: there is no universally optimal detection algorithm for all possible distributions of normal and anomalous data.

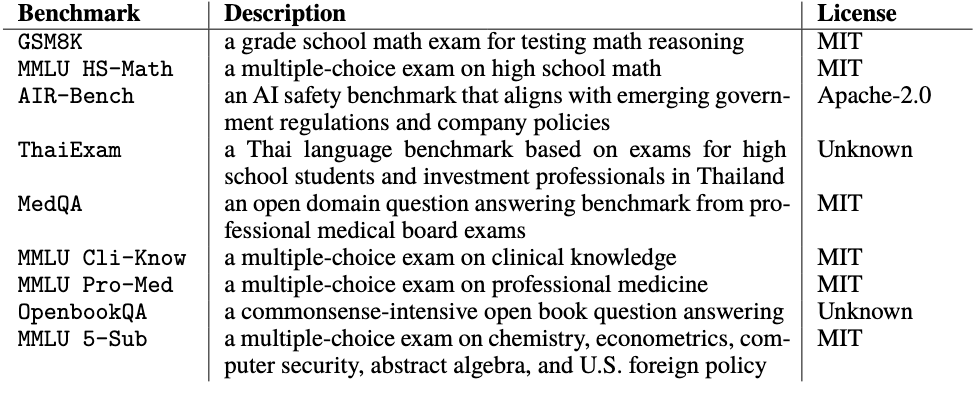

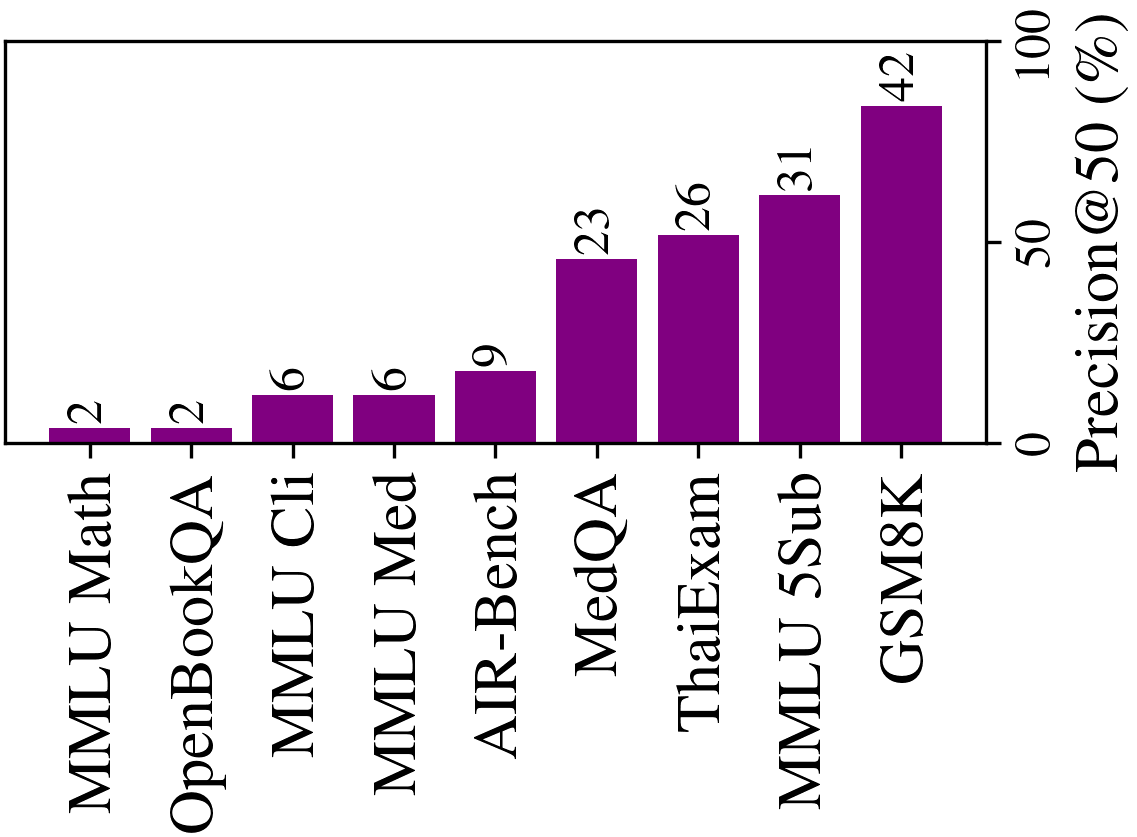

Next, we demonstrate that our framework effectively guides expert review to identify flawed questions across nine benchmarks covering capability and safety assessments, including multilingual and domain-specific datasets such as Thai language understandin, medical reasoning, and mathematical problem solving. We list these nine benchmarks in Table 1. For each benchmark, we collect binary response matrices from the HELM leaderboard and evaluate performance using Precision@k = TP(k)/k, where TP(k) is the number of truly invalid questions among the top k flagged questions. Precision@k quantifies the practical value of our methods in real-world settings where human annotators can review only a limited number of questions. As shown in Figure 4, our methods effectively guide experts, with up to 84% of flagged questions confirmed as invalid upon manual inspection. This demonstrates that the proposed approach provides a cost-efficient and scalable solution for benchmark auditing.

Next, we examine the invalid question patterns in the benchmarks, using ThaiExam as an example. ThaiExam is a Thai-language benchmark derived from examinations for high school students and investment professionals in Thailand. A native Thai-speaking expert reviewed the dataset, guided by our signals, and identified numerous questions exhibiting cultural biases and linguistic ambiguities, issues often imperceptible to non-native speakers, even with translation tools. Beyond errors in answer keys, we identify two challenges unique to Thai-language datasets:

- Cultural value alignment: The ThaiExam dataset aggregates questions from multiple sources. Questions, particularly from the logical reasoning TGAT exam subset, often embed cultural norms. This necessitates culturally-specific judgments over objective deduction, creating ambiguity and lacking a single correct answer, thus complicating fair evaluation.

- OCR extraction errors: Imperfect OCR from source images introduces grammatical inaccuracies and semantic distortions. These errors significantly impact validity, such as misrecognizing the visually similar Thai numerals ๗ (seven) as ๓ (three), which alters question meaning and invalidates keys.

Read our paper for invalid question patterns identified in other benchmarks.

Finally, we explore prompting ChatGPT O1 to review the first 100 questions from GSM8K, a saturated benchmark that exhibits severe grading issues in HELM. Human inspection reveals that approximately 30% of the 100 questions are invalid—3.3% are Ambiguous Questions, 3.3% are Incorrect Answer Keys, and 93.3% are Grading Issues. When prompted using our framework, LLMs accurately identified invalid questions with 98% precision, confirming their potential as scalable assistants for benchmark auditing. These results suggest that LLM-based review provides a practical path toward semi-automated benchmark validation.

Conclusion

This study advances AI evaluation by integrating measurement-theoretic methods into benchmark revision. Our framework empowers curators and users to detect and correct flawed questions, promoting fairer and more trustworthy assessments. By analyzing LLM response patterns, we reveal subtle issues that heuristic checks often miss, demonstrating that benchmark quality cannot be assumed from domain expertise alone—it must be inferred from LLM response patterns. By supporting iterative, external audits rather than one-off revisions, our pipeline encourages a cultural shift from “publish-and-forget” to continuous stewardship. We recommend that future benchmark developers adopt this framework to identify flawed questions and ensure higher quality standards before release.