When teams of humans and robots work together to complete a task, communication is often necessary. For instance, imagine that you are working with a robot partner to move a table, and you notice that your partner is about to back into an obstacle they cannot see. One option is explicitly communicating with your teammate by telling them about the obstacle. But humans utilize more than just language—we also implicitly communicate through our actions. Returning to the example, we might physically guide our teammate away from the obstacle, and leverage our own forces to intuitively inform them about what we have observed. In this blog post, we explore how robot teams should harness the implicit communication contained within actions to learn about the world. We introduce a collaborative strategy where each robot alternates roles within the team, and demonstrate that roles enable accurate and useful communication. Our results suggest that teams which implicitly communicate with roles can match the optimal behavior of teams that explicitly communicate via messages. You can find our original paper on this research here.

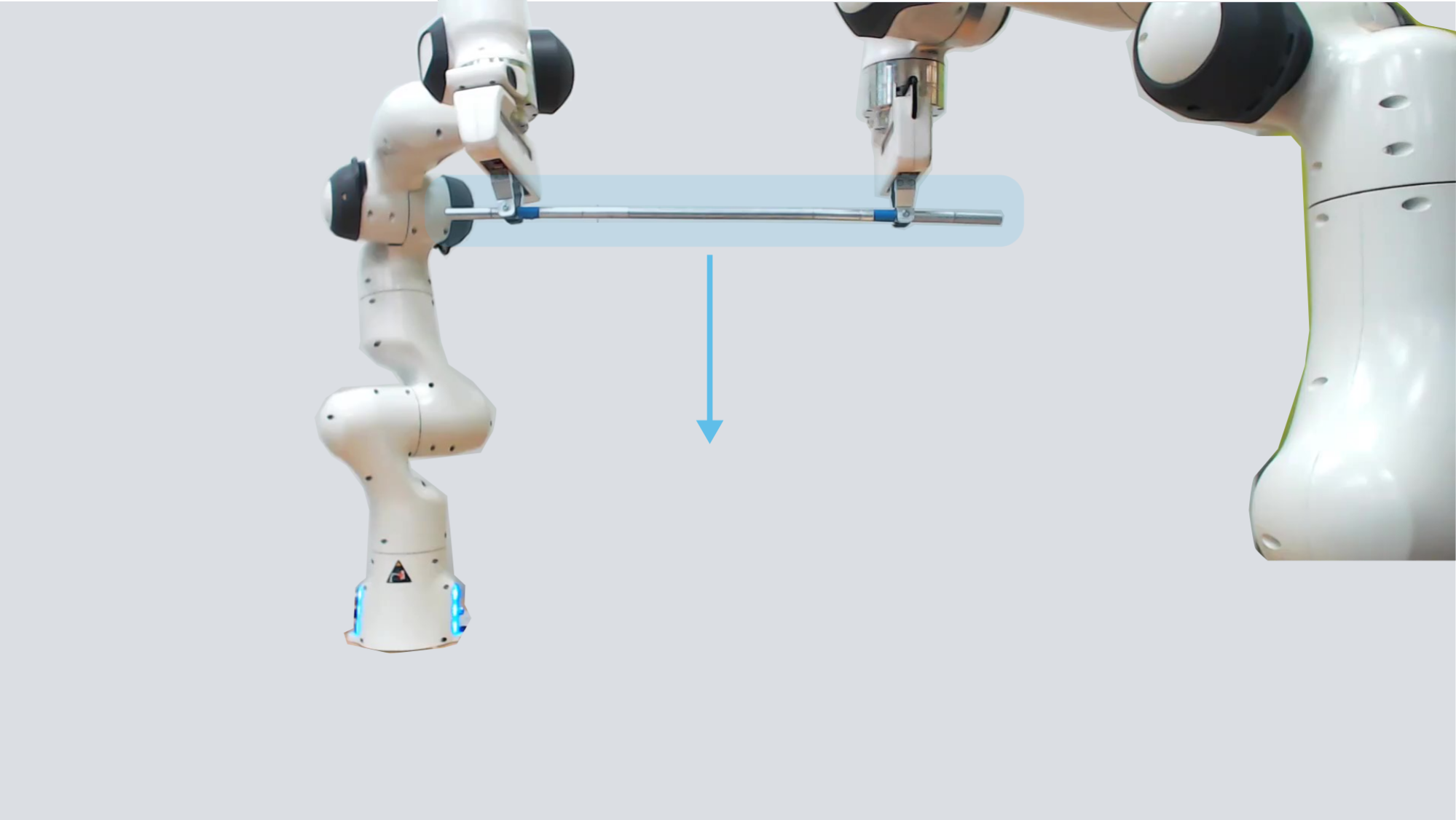

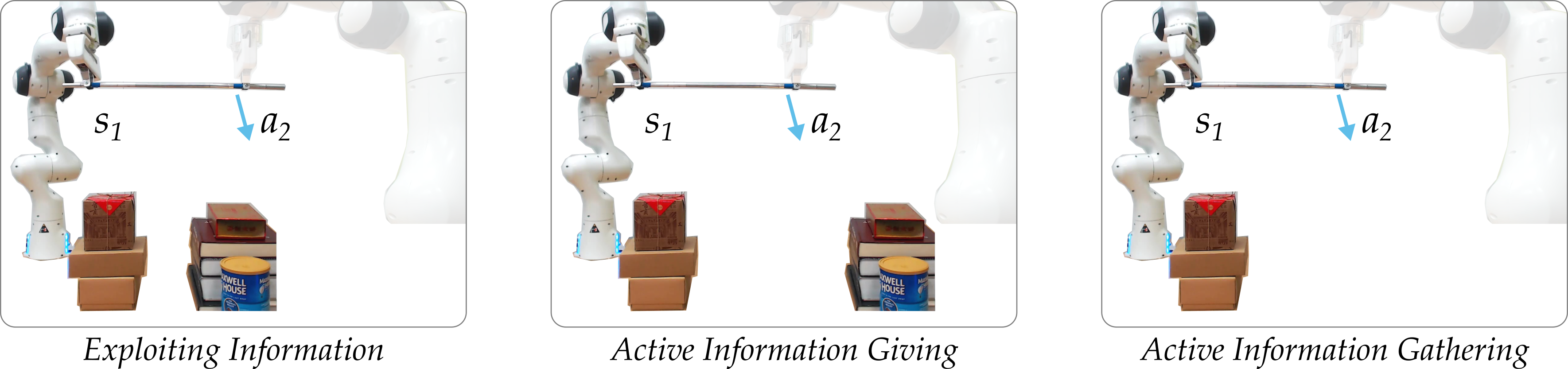

Motivation. Consider the task shown below. Two robots are holding a metal rod, and they both want to place this rod on the ground:

Because the robots share a common goal, they should collaborate, and work with one another to complete the task. But—although robots share a goal—they have different information about the world! The robot on the left (we’ll refer to it as robot #1) sees a nearby pile of boxes:

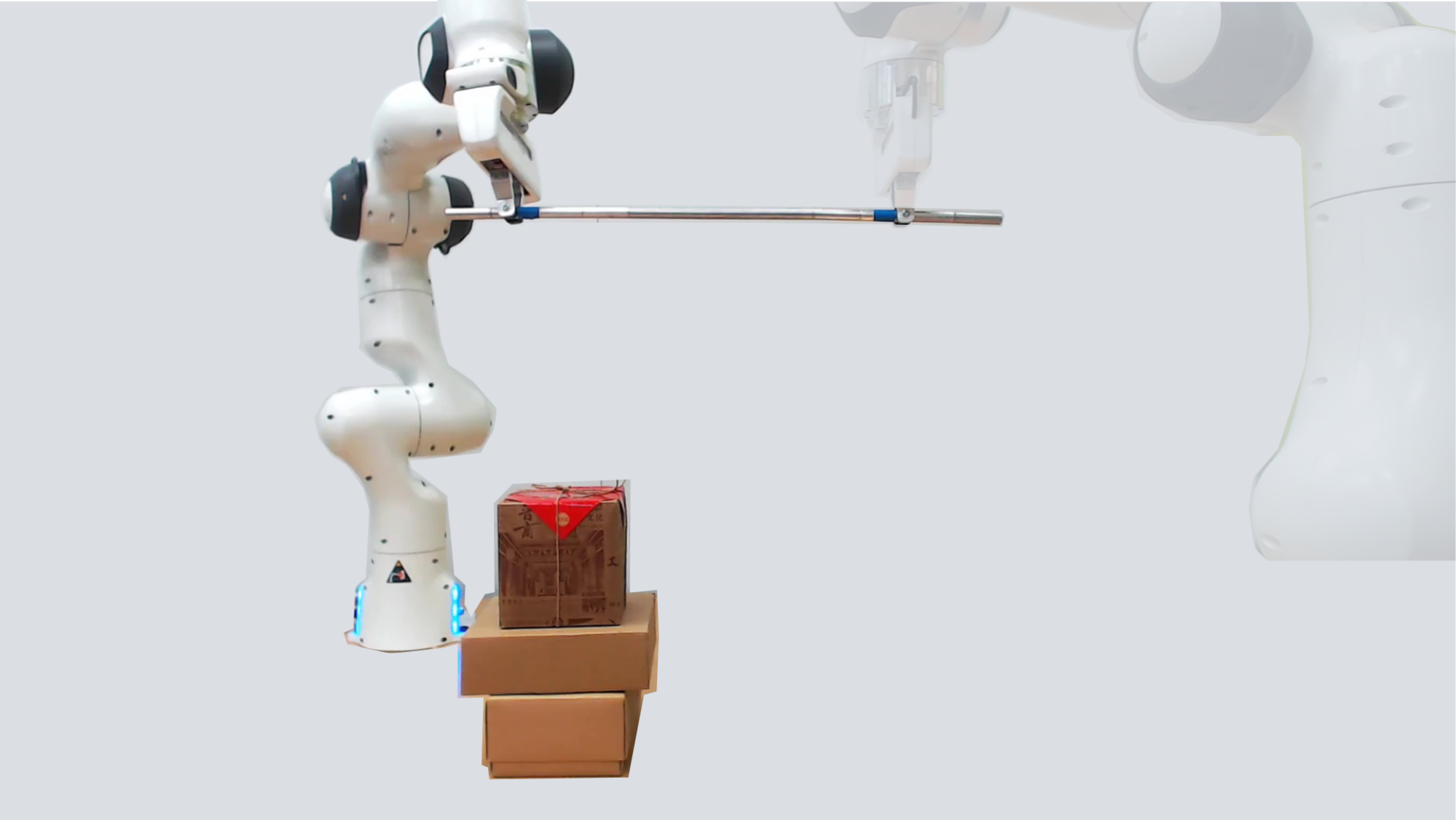

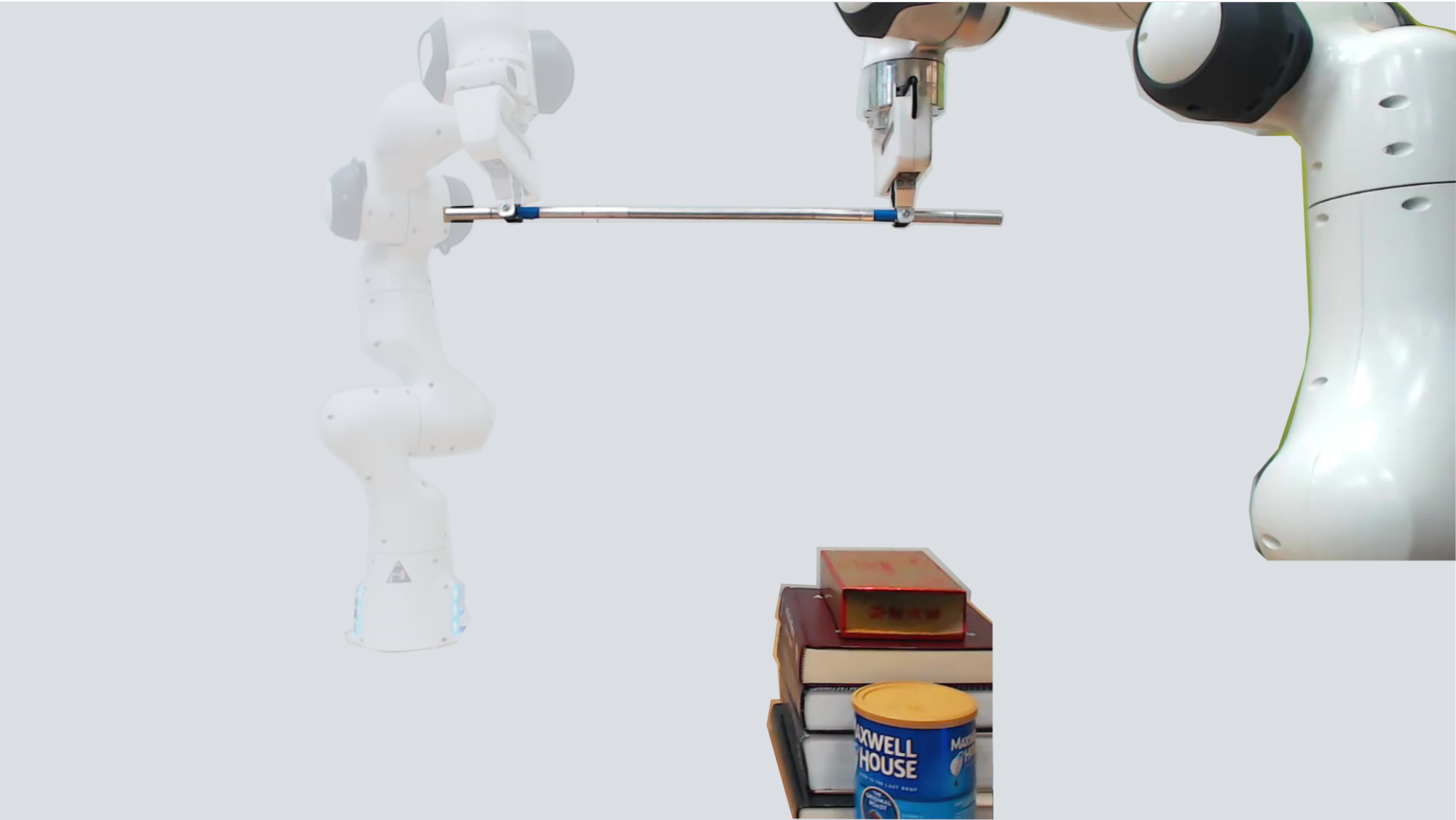

The robot on the right (we’ll refer to it as robot #2) doesn’t see these boxes. Instead, it observes a pile of books that robot #1 cannot detect:

Both agents have incomplete observations of the world—they see some, but not all, of the obstacles in their way. Without a common understanding of all of the obstacles, it is hard for the robots to collaborate!

What’s most important here is that the robots are decentralized: i.e., each robot has its own controller, and makes its decisions independent of its partner. Because the robots are independent, one naive strategy would simply be for each robot to simply try and avoid the obstacles that it can see. In other words, robot #1 will move to avoid the boxes, and robot #2 will move to avoid the books. Under this strategy, the two agents make no effort to communicate: instead, they solve the problem while ignoring the actions that their partner makes. But ignoring our partner’s actions means that we miss out on valuable information, which here causes the independently acting robots to collide with the boxes!

These robots are intelligent: they devise plans to optimally complete the task while accounting for what they can observe. But they aren’t collaborative: they fail to harness the information that is contained within their partner’s decisions. Striking the balance between actions that optimally solve the task and actions that communicate about the world is notoriously difficult (see Witsenhausen’s counterexample). The goal of our research is to develop robots that learn from their partner’s actions in order to successfully collaborate during tasks that require communication.

Insight and Contributions. Correctly interpreting the meaning behind our partner’s actions is hard. Take the video above, and assume you have no prior knowledge over what the robots are trying to do: at each given timestep, they could be exploiting what they know, actively giving information to their partner, or even actively gathering information from their teammate. Robots—like people—can take actions for many different reasons. So when we observe our partner applying a force, what (if anything) should we learn from that action? And how do we select actions that our partner can also interpret? Our insight is that we can use roles:

Collaborative teammates can learn from each other’s actions when the team is separated into roles, and each role provides a distinct reason for acting

In what follows, we formalize the concept of roles, and demonstrate that robots which alternate roles can accurately exchange information through their actions. Next, we implement roles in simulated and real robot teams, and explore how they facilitate learning. Although this research focuses on teams composed entirely of robots, we are excited about leveraging the insights gained from these settings to also enable implicit communication in human-robot teams.

Learning in Real-Time with Roles

Here we mathematically define our problem setting and show why roles are necessary. We also use our theoretical results to answer questions such as: What is the best way to change roles? When do we need to alternate roles? And how should I behave within each role?

For simplicity, we will focus on teams with two robots. However, the ideas which we discuss here can also be extended to teams with an arbitrary number of members!

Notation. Let \(s\) be the state of the world, which contains all the relevant information needed to represent the robots and environment. We break this state into two components: \(s = [s_1, s_2]\). Here \(s_1\) is the state of robot #1 (e.g., its arm configuration and the position of the boxes) and \(s_2\) is the state of robot #2 (e.g., its arm configuration and the position of the books). These states capture the different information available to each agent, and are shown in the thought bubbles below:

So the states \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) express what each agent knows. But how can the robots gain new information about what they don’t know? We assert that robots should leverage their partner’s actions. Returning to the image above, \(a_1\) is the action taken by robot #1 (and observed by robot #2), while \(a_2\) is the action taken by robot #2 (and observed by robot #1). In this example, actions are the physical forces and torques that the robots apply to the metal rod.

Under our approach, each robot utilizes these observed actions—in addition to their own state—to make decisions. More formally, each agent has a policy that defines the likelihood of taking a specific action as a function of their current state and their partner’s action. For instance, we write the policy of robot #1 as: \(\pi_1(a_1 \mid s_1,a_2)\). A key here is that these decision making policies depend on how the robot’s partner behaves!

Interpreting My Partner’s Actions. Let’s imagine that we are robot #1. If we know the full state \(s\), we can make optimal decisions. But we don’t; we only have access to \(s_1\), and we are relying on \(a_2\) to learn about the rest of the state that we cannot directly observe (i.e., \(s_2\)). Put another way, we need to interpret what our partner’s actions mean about the world. But this is hard: people and robots can choose actions for many different reasons.

Consider the example above. In each block, we observe the same robot action, but we interpret it in a different way based on what we think our partner is doing.

- Exploiting Information: our partner is moving to the right in order to avoid an obstacle we cannot see.

- Active Information Giving: our partner is purposely trying to convey information to us by exaggerating their behavior and moving towards the obstacle.

- Active Information Gathering: our partner is trying to elicit information from us by pulling us in a different direction and watching how we respond.

Based on what we think our partner is trying to do (exploit, give, or gather) we assign a different meaning to the same action (obstacle in center, obstacle on right, no obstacle at all). Put another way, we need to understand how our partner makes decisions in order to correctly interpret their actions.

Infinite Recursion. This intuition matches our mathematical findings. When deriving the optimal policy for robot #1, we discover that our policy depends on our partner’s policy:

\[\textcolor{blue}{\pi_1(a_1 ~|~ s_1, a_2)} = f_1(..., \textcolor{orange}{\pi_2(a_2 ~|~ s_2, a_1)}, …)\]And, similarly, our partner’s policy depends on our own policy:

\[\textcolor{orange}{\pi_2(a_2 ~|~ s_2, a_1)} = f_2(..., \textcolor{blue}{\pi_1(a_1 ~|~ s_1, a_2)}, …)\]This interdependence results in infinite recursion. Putting the above equations into words, when solving for my partner’s policy I need to solve for my partner’s understanding of my policy, which in turn relies on my partners understanding of my understanding of their policy, and so on. Expressed more simply: when robot teammates have no context for interpreting their partner’s actions, they fall down an infinite rabbithole of what do you think I think you think…1

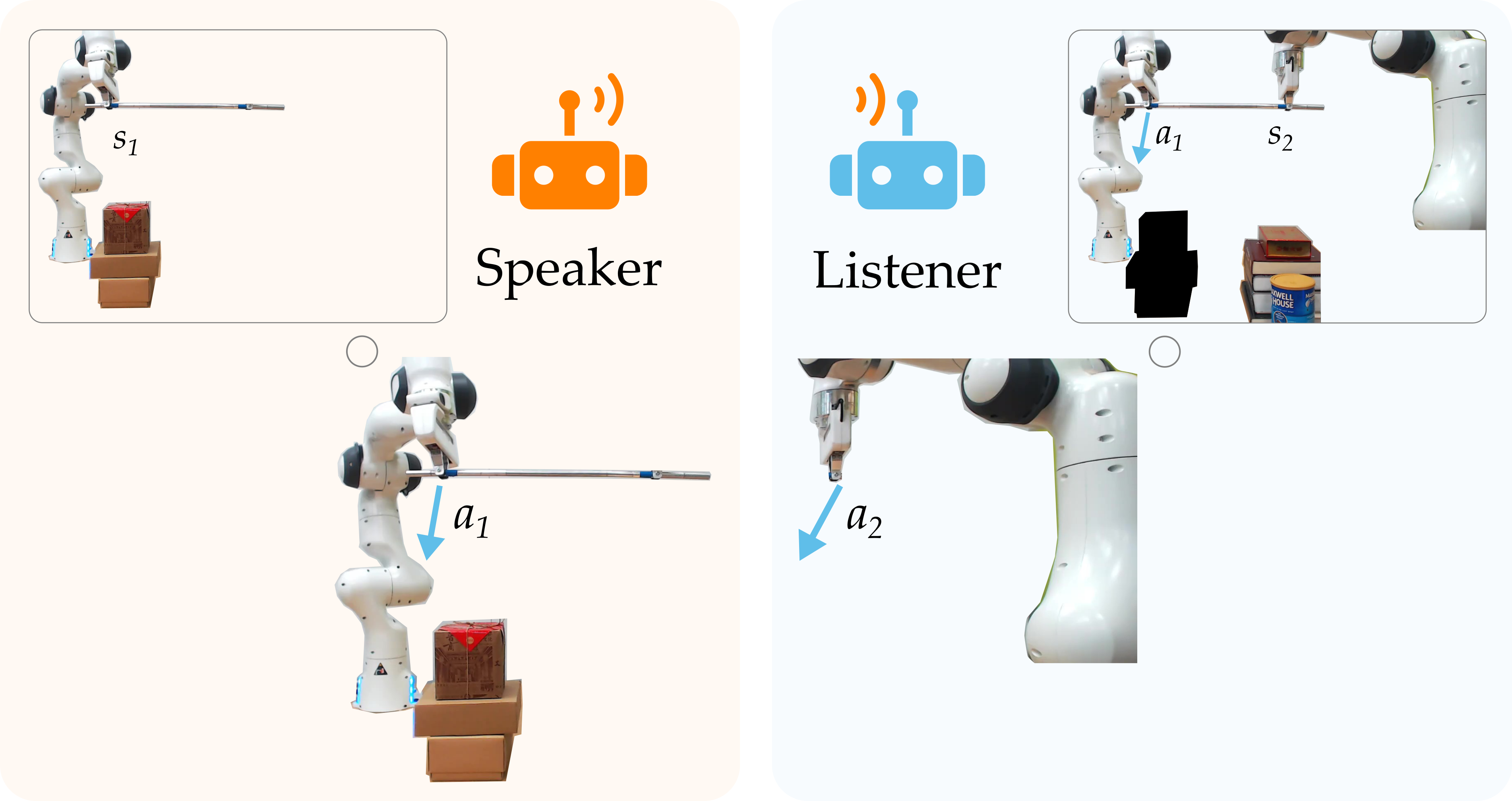

Introducing Roles. Roles provide the structure necessary for breaking this recursion and understanding what our partner is trying to do. We introduce two classes of roles: a speaker and a listener.

As shown above, speakers make decisions based only on their current state. Here robot #1 is the speaker, and it chooses an action to avoid the boxes. Because the listener knows that its partner is exploiting what it sees, it can correctly interpret what these actions mean. Returning to the diagram, robot #2 listens to robot #1, and realizes that \(a_1\) indicates that there is an obstacle next to the books. Equipped with this learned information, now robot #2 also moves left to avoid the books!

Understanding Roles. We explore how roles can help robot teams communicate and learn within simple contexts2. In these simplified settings, we derive theoretical answers to the following questions:

- Do robots need to alternate roles? Yes. If teammates never change speaker and listener roles, the closed-loop team can actually become unstable. Intuitively, imagine that you are always a speaker. You can use your actions to tell your partner about what you see, but you never get the chance to learn from their actions and update your own behavior!

- How should robots alternate roles? Changing roles at a predetermined frequency. We have a theorem that demonstrates that the team’s performance improves the faster that the agents change roles. One key advantage of this switching strategy is that it requires no common signals during the task (with the exception of a world clock that both agents can access).

- How effective are roles? In certain scenarios, decentralized robots that leverage roles can match the optimal behavior of centralized teams (in which both robots already know the entire state). Hence, when we use roles, we enable implicit communication to be just as expressive as explicit communication.

- What if I only have a noisy observation of my partner’s actions? As long as this noise is unbiased (i.e., zero mean), it’s fine to treat your noisy observations as if they are your partner’s true actions. Sensor noise is common, so it’s important that our approach is robust to this observation noise.

- When I’m the speaker, how should I behave? Usually the speaker should simply exploit what they observe; however, there are also cases where the speaker should actively give information and exaggerate its behavior3. We are excited that this exaggeration arises naturally as a result of optimizing our roles, without being preprogrammed.

Summarizing Roles. When teammates try to interpret their partner’s actions without any prior information they easily get confused. There are many different ways to explain any given action, which makes it hard to determine what—if anything—the robot should learn. We resolve this confusion by introducing speaker and listener roles for decentralized robot teams. These roles provide a clear reason for acting, and enable the listener to correctly interpret and learn from the speaker’s choices. We emphasize that the resulting learning is real-time: the robots don’t need access to offline training, simulations or additional demonstrations4. Instead, they learn during the current task by alternating roles.

Leveraging Roles in Robot Teams

We evaluate how robot teams can leverage roles in simulated and real environments. In the simulation experiments, we explore how different amounts of communication affect performance, and compare our role allocation strategy to teams that communicate via explicit messages. In the robot experiments, we revisit the motivation example from the beginning of this blog post, and demonstrate how roles enable real-time learning and collaboration. Our simulation and experimental settings involve nonlinear dynamics, and are more complex than the simple settings in which we theoretically analyzed roles.

Simulations: Understanding the Spectrum of Communication

Imagine that you are working with a partner to carry a table across the room. There are many objects within the room that you both need to avoid, but you can’t see all of these obstacles. Instead, you need to rely on your partner for information!

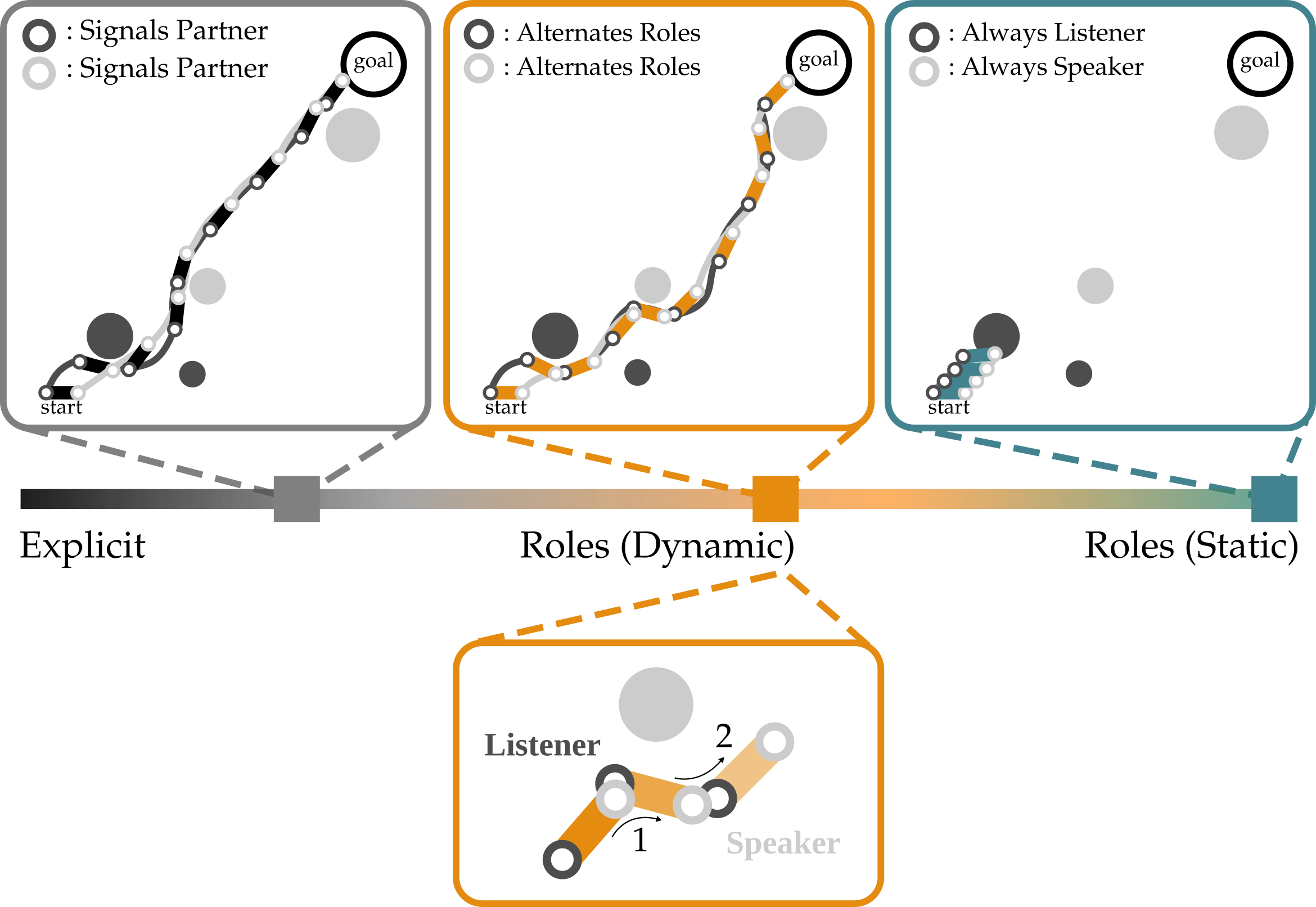

Spectrum. We explore how a team of robot agents can complete this table carrying task under different levels of communication.

- Centralized. Both agents know exactly what the full state is, and there is no need for communication.

- Explicit. Each agent sends a message containing the position and geometry of the nearest obstacle to its teammate.

- Roles (Dynamic). The team divides into speaker and listener roles, and the agents implicitly communicate through actions.

- Roles (Static). One agent is always a speaker, and the partner is always a listener. The agents do not change roles.

Viewed together, these different types of communication form a spectrum. Within this spectrum, we are interested in how using and alternating roles compares to the alternatives.

Experimental Overview. Above is one example of the table carrying task. The table starts in the bottom left corner, and the agents work together to collectively transport this table to the goal region (red circle, top right). Here the agents are the circles at the ends of the table—notice that one agent is colored a \(\mathbf{\textcolor{gray}{\text{light gray}}}\), and the other agent is a \(\mathbf{\textcolor{black}{\text{dark gray}}}\). The static circles are obstacles that the team is trying to avoid. Importantly, the color of these circles matches the color of the robot which can observe them: e.g., only the dark gray agent that starts on the right can see the bottom left obstacle. In our experiments, we vary the number of obstacles, and test how frequently each type of team successfully reaches the goal.

Results. We found that robots which implicitly communicate via roles approach the performance of teams that explicitly communicate by sending messages. See the example below:

On the top, we observe that Explicit and Roles (Dynamic) teams avoid the obstacles, while teams that maintain fixed roles fail. On the bottom, we visualize how implicit communication works in practice. (1) when the speaker approaches an obstacle it can observe, it abruptly moves to the right. (2) the listener realizes that the speaker must have changed directions for a reason, and similarly moves to avoid the obstacle which it cannot directly observe.

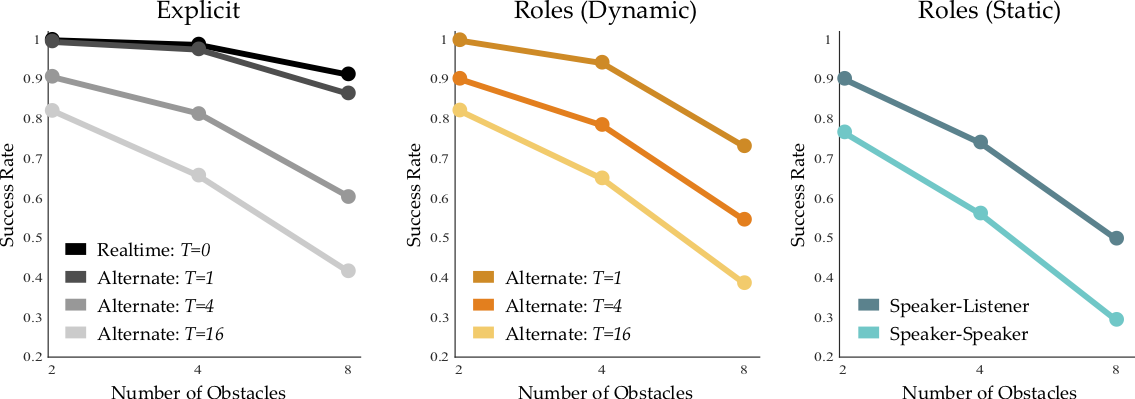

Aggregating our results over 1000 randomly generated environments, we find that Explicit and Roles (Dynamic) perform similarly across the board:

This plot shows the fraction of trials in which each team reached the goal: higher is better! Imagine that you could only talk to your partner about the obstacle locations every 4 timesteps: in this case, our simulated teams reach the goal around 80% of the time. But what if you never spoke, and instead changed roles every 4 timesteps? Interestingly, the simulated teams in this condition perform about the same, and still reach the goal about 80% of the time! Our results demonstrate the power of using roles to structure implicit communication. But—in order to be effective—these roles must change within the task. When the team does not change roles, their performance falls below the Explicit baseline.

Experiments: Using Roles to Learn and Collaborate

Now that we understand what roles are, and can use them to solve a simulated task, let’s return to the problem which originally motivated our research. We have two robots that are trying to place a rod down on the table. These robots are controlled on separate computers, and cannot send messages to one another; instead, they need to communicate information about the world through their actions.

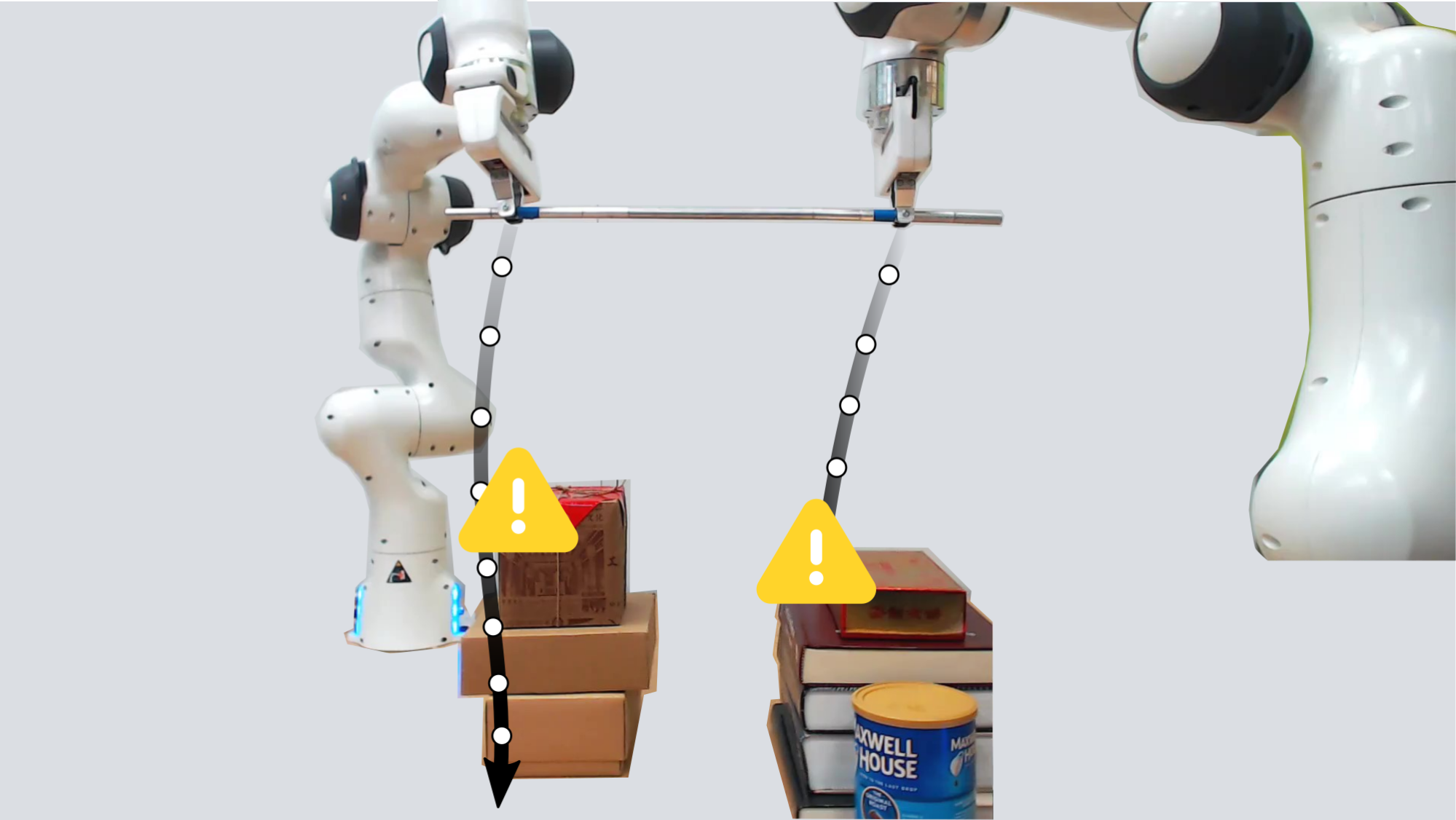

Independent vs. Roles. The robots attempt to complete the task in two different scenarios. We’ve already talked about the first, where each robot tries to independently solve the problem while ignoring their partner’s actions. Now let’s explore the second, where the robot follow and exchange roles during interaction.

Above we display the plans that independent robots (left) and robots using roles (right) come up with. When the robots plan to avoid what they can see, they end up moving in different directions: robot #1 wants to go in front of the boxes, while robot #2 moves behind the books. During implementation, these conflicting plans apply opposite forces along the rod and ultimately cancel each other out. Because the robots fail to collaborate, a collision occurs!

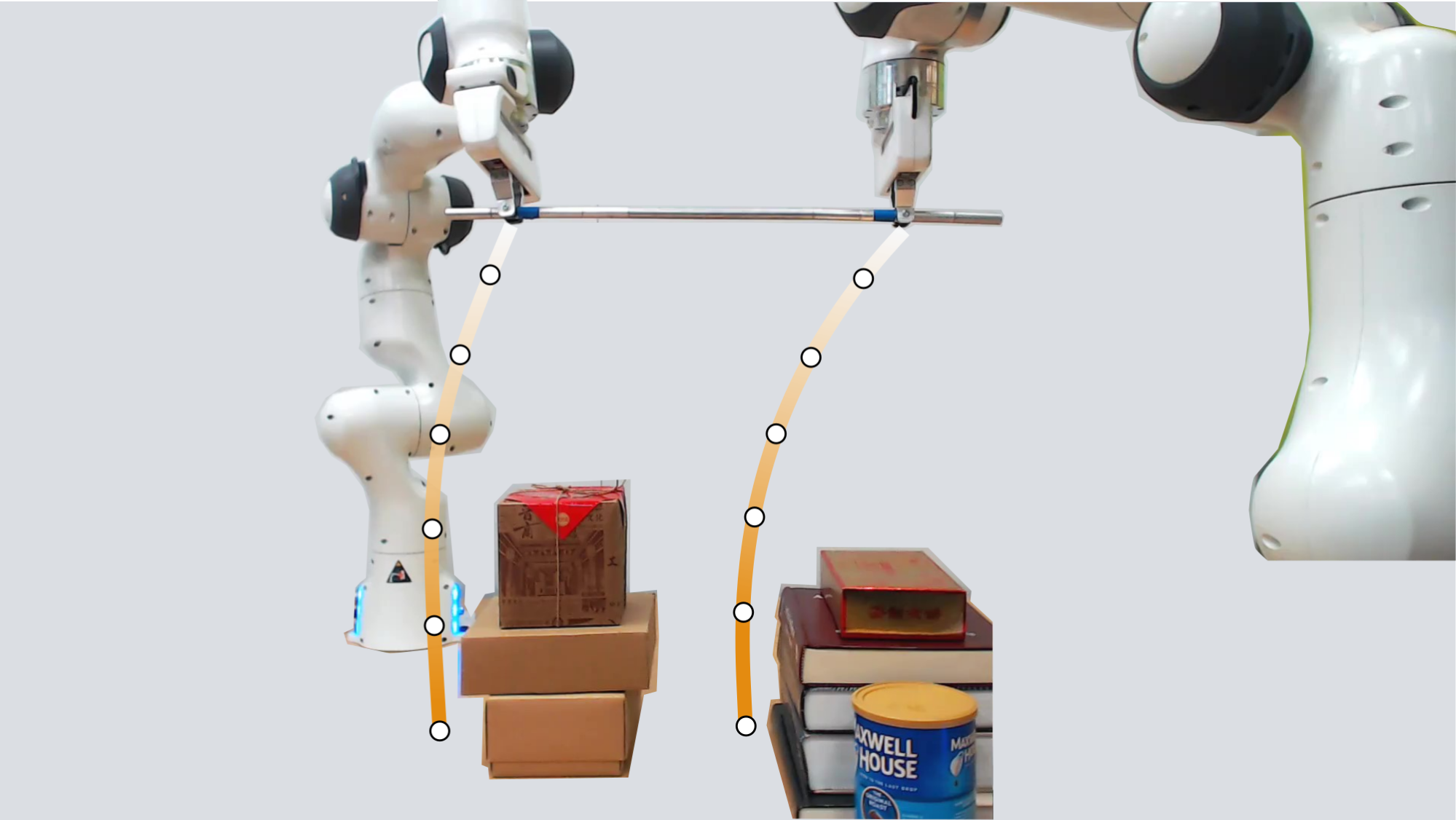

By contrast, robots that leverage roles to communicate about the world can coordinate their actions in real-time to avoid both the boxes and the books:

Breaking down this video, you’ll notice that at the start the robots are moving right down the middle (and look like they might fail again). But as robot #1 gets closer to the boxes, it starts to veer to the left—robot #2 learns from this action, updates its understanding of the world, and changes its behavior to avoid the boxes!

Collaboration. When we compare the performance of independent robots to robots that use roles, one key difference is how these teams coordinate their behavior. Since both robots have the same objective (putting the rod on the table) it makes sense that they should align their decisions and agree in their plans. But—because these robots are controlled independently—it’s not obvious how to coordinate.

These same problems arise when humans work with robots (or other humans). Because we have our own ideas, observations, and understanding of the world, we come up with plans that may not match our teammate! Our experiments, however, indicate that roles can help bridge this gap:

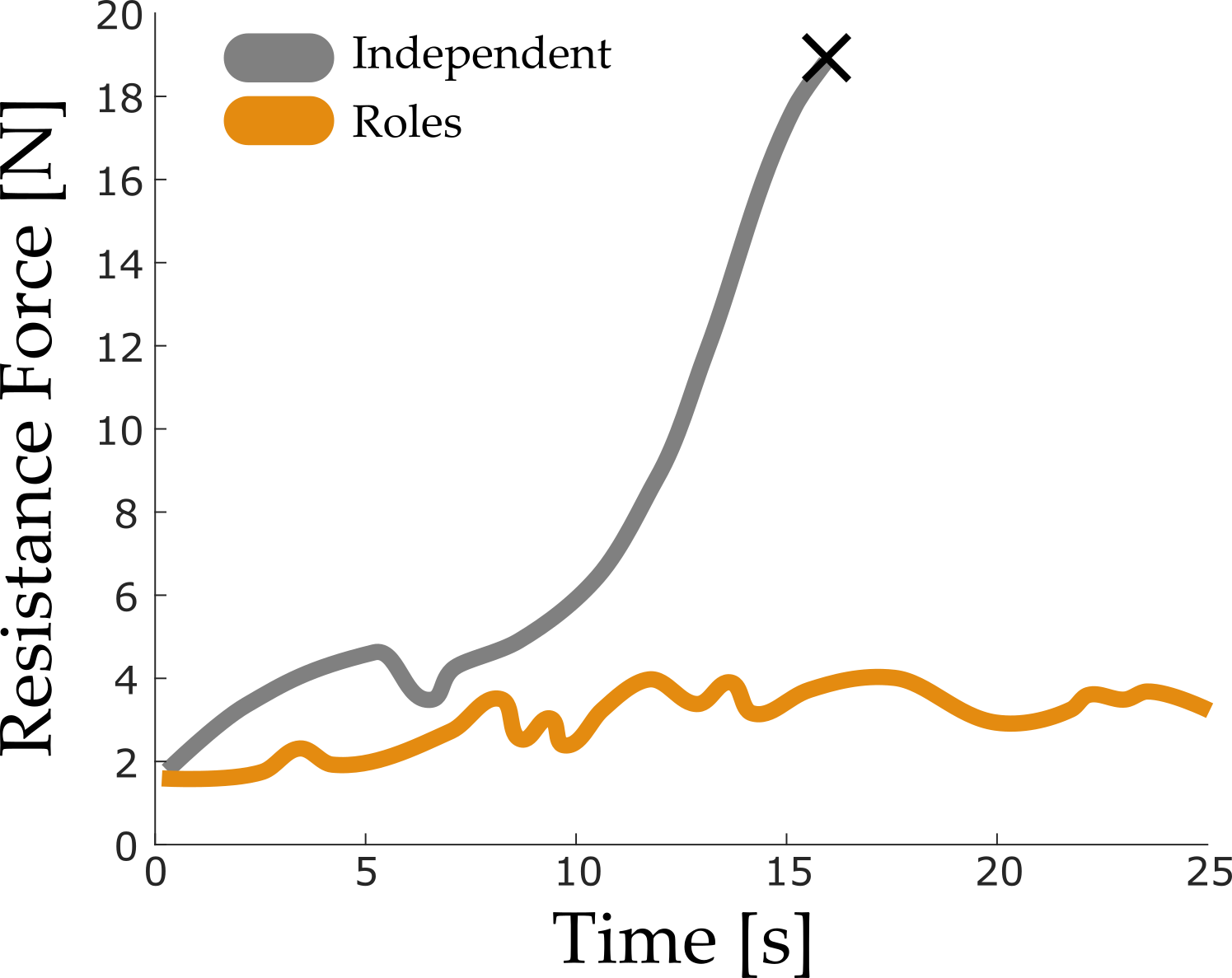

Above we plot the amount of resistance force that the robots are applying to each other when carrying the metal rod (lower is better). In \(\mathbf{\textcolor{gray}{\text{gray}}}\) we plot robots that act independently—these two agents resist one another, ultimately leading to the collision we marked with an “x”. The \(\mathbf{\textcolor{orange}{\text{orange}}}\) plots are much better; here the teammates use roles to implicitly communicate and recover a coordinated policy. What’s key here is that roles not only enable learning, but this learning is also useful for improving teamwork and increasing collaboration.

Key Takeaways

We explored how we can harness the implicit information contained within actions to learn about the world. Our main insight is that introducing roles enables teammates to correctly interpret the meaning behind their partner’s actions. Once these roles are defined, robots can learn in real-time and coordinate with their teammates. To summarize our findings:

- Without any imposed structure, learning from our partner’s actions leads to infinite recursion (what do you think I think you think…).

- Robots that alternate roles are able to implicitly communicate through their actions and learn in real-time, without offline training or demonstrations.

- This communication is informative: teams that learn from their partner’s actions via roles are able to understand as much about the world as teams that explicitly communicate by speaking or sending messages.

- This communication is useful: robots that learn via roles are more collaborative, and better align their actions with their partner.

Overall, this work is a step towards human-robot teams that can seamlessly communicate during interaction.

If you have any questions, please contact Dylan Losey at: dlosey@stanford.edu or Mengxi Li at: mengxili@stanford.edu. Dylan Losey and Mengxi Li contributed equally to this research.

Our team of collaborators is shown below!

This blog post is based on the CoRL 2019 paper Learning from My Partner’s Actions: Roles in Decentralized Robot Teams by Dylan P. Losey, Mengxi Li, Jeannette Bohg, and Dorsa Sadigh.

For further details on this work, check out the paper on Arxiv.

-

Hedden, Trey, and Jun Zhang. “What do you think I think you think?: Strategic reasoning in matrix games.” Cognition 85.1 (2002): 1-36. ↩

-

We consider controllable linear dynamical systems that use linear feedback control laws. ↩

-

Dragan, Anca D., Kenton CT Lee, and Siddhartha S. Srinivasa. “Legibility and predictability of robot motion.” ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 2013. ↩

-

This makes our problem setting different from multi-agent reinforcement learning, where the robots have access to training data and offline simulations. ↩