Every year, more people die from hospital-acquired infections than from car accidents. This means when you are admitted to a hospital, there is a 1 in 30 chance your health will get worse than had you not gone to the hospital at all.

This is a dire situation, but one hospitals can easily improve through better hygiene. Hand hygiene is the first line of defense in preventing the spread of infections not only in hospitals, but also in public spaces like airports and restaurants. This is already well known, so the issue is not one of ignorance but of vigilance; automated verification techniques are needed to check for hand washing. Among the many technological solutions to this problem, perhaps the simplest is to use the most common human strategy – visually confirm whether people are washing their hands or not – with computer vision.

Developing such a technological solution has been a multi-year project being done by the Stanford Partnership in AI-Assisted Care (PAC) and many collaborators around the world. Much remains to be done, but we hope this technology can help hospitals decrease infection rates and improve patients’ health.

Why Vision

Today, hospitals reinforce proper hand hygiene through educational tools such as medical school classes, flyers posted on bulletin boards, and weekly staff meetings. The World Health Organization has even proposed the Five Moments of hand hygiene, explicitly defining when a healthcare worker should wash their hands. To measure hand hygiene compliance, hospitals track hand hygiene using RFID cards or badges worn by employees. While this works to some extent, there are workflow disruptions such as swiping the RFID card by the soap dispenser when rushing into a new room. This stems from technical reasons: normal RFIDs have short range, and “active” RFIDs with longer range are constrained by their directional antenna and need batteries. Clearly, a new solution that does not have the drawbacks of RFID techniques is needed.

Computer Vision and Hospitals

We worked with Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford and developed a new and advanced way to track hand hygiene. It uses cutting-edge computer vision and does not require a clinician to change their daily routine. While computer vision has been used for medical imaging, there hasn’t been much use in the physical hospital space. Luckily, computer vision has been applied in physical spaces for another problem: self-driving cars. Self-driving cars use tons of sensors to understand their environment. Can we use some of these sensors inside hospitals to better understand the healthcare environment?

Depth Sensors

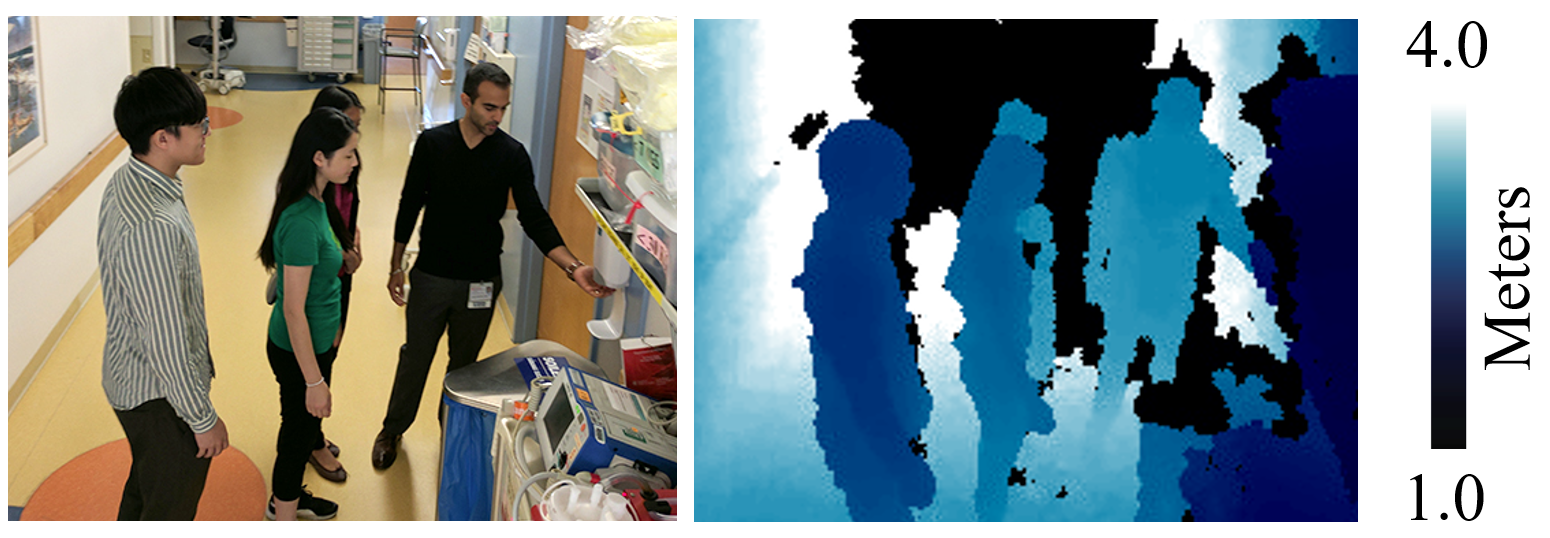

Depth sensors (e.g., Xbox Kinects) are like normal cameras but instead of recording color, they record distance. In a normal color image, each pixel denotes a color. In a depth image, each pixel denotes the “distance” to the pixel in real-world space. This is usually a floating point number such as 1.337 meters.

(Left) Color photo of the hospital, taken with a cell phone. (Right) Corresponding depth image taken by our sensor on the ceiling. Darker colors indicate objects closer to the depth sensor.

In the depth image above, notice how you can’t really see the people’s faces, but can still tell what they’re doing. This protects our users’ privacy, which is important in hospitals To develop and validate our computer vision technology, we installed depth sensors on the ceiling at two hospitals. One was a children’s cardiovascular unit and the other was an adult intensive care unit (ICU).

Our depth sensors installed on the ceiling of a children’s hospital.

With depth sensors installed at two different hospitals, we can then use 3D computer vision tools to automatically measure hand hygiene. This involves three steps:

- Detecting the healthcare staff.

- Tracking the staff as they walk around the unit.

- Classifying their hand hygiene behavior.

Pedestrian Detection

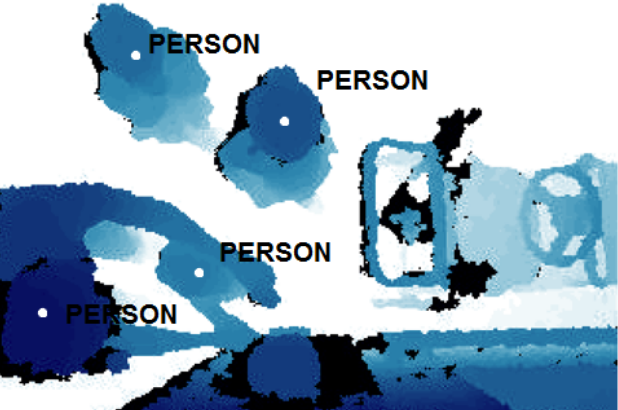

Continuing with our self-driving car analogy: to understand the environment we need to first detect people.While there exists many object detection methods, most of them are developed for color RGB images. Instead, we chose to use a previous approach that can run on any type of image by leveraging two aspects of the problem: that people typically occupy small amounts of space in a given image of a room, and that in depth images people typically look like ‘blobs’ that clearly stand out against the background of the floor.

Entries of the dictionary. Each dictionary entry contains a synthetic image, corresponding to how a person would look like, had they been standing at that position.

One way to detect people is to determine an occupancy grid over the ground, which is a binary matrix indicating whether a person is occupying a particular position in the ground plane. By converting the ground (i.e., floor of a room) into a discrete grid we can “imagine” a person at that position by rendering a blob, roughly the same height as a person, at every point in this grid. We can create a dictionary containing blobs at every single point on the ground plane (remember: because we synthetically created these blobs, we know their exact 2D and 3D position). For multiple people, we can render multiple blobs in the scene. During test-time, all we need is a “blob” image. This can be done with any foreground/background subtraction method or object segmentation algorithm. Now, given this test-time blob image, we can perform a k-nearest neighbor search into this dictionary to find the positions of each blob.

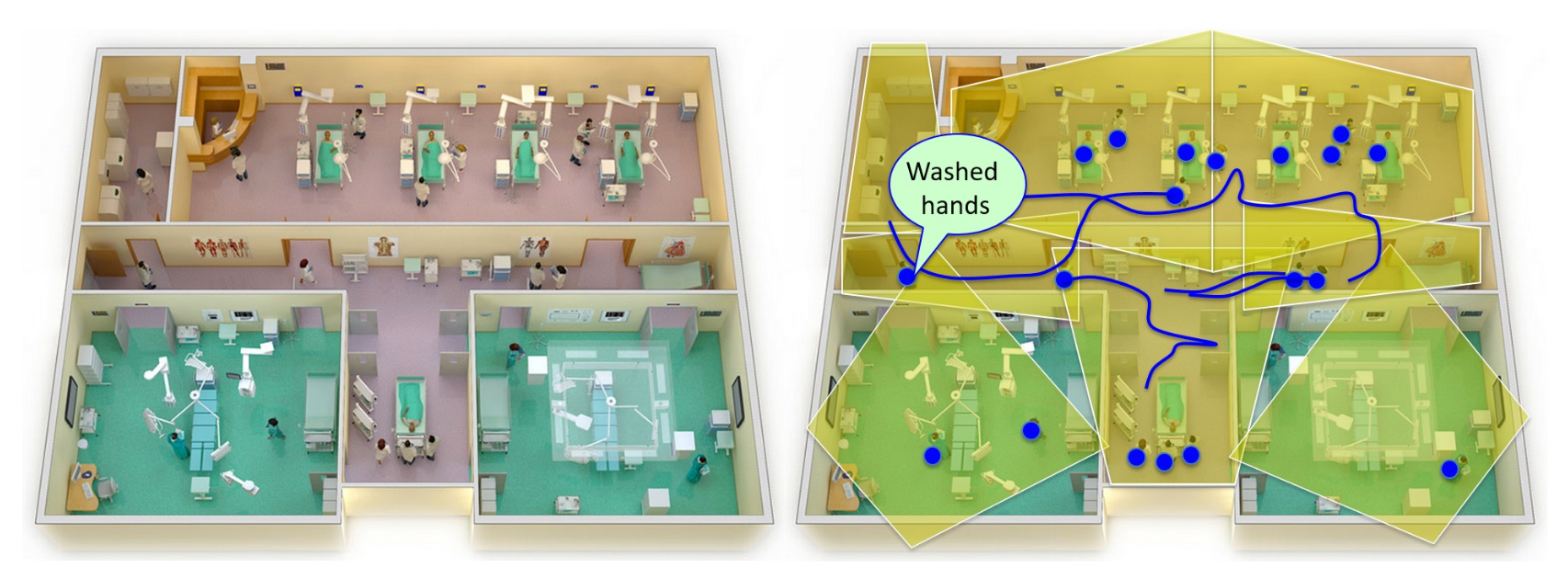

Tracking Across The Hospital Unit

In order to build a truly smart hospital, we need to use sensors spread out across the entire hospital unit. Since not everything happens in front of one sensor, we also need algorithms that can track people across sensors. Not only can this provide details for hand hygiene compliance, but it can also be used for workflow and spatial analytics. Formally, we want to find the set of trajectories \(X\), where each trajectory \(x \in X\) is represented as an ordered set of detections, \(L_x = (l_x^{(1)} ,...,l_x^{(n)} )\), representing the detected coordinates of pedestrians. The problem can be written as a maximum a-posteriori (MAP) estimation problem.

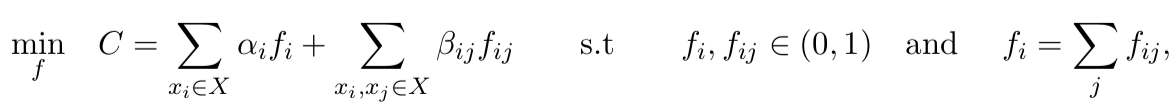

Next, we assume a Markov-chain model connecting every intermediate detection \(l_x^{(i)}\) in the trajectory \(X\), to the subsequent detection \(l_x^{(i+1)}\) with a probability given by \(P(l_x^{(i+1)} | l_x^{i})\). We can now formulate the MAP task as a linear integer program by finding the flow \(f\) that minimizes the cost \(C\):

where \(f_i\) is the flow variable indicating whether the corresponding detection is a true positive, and \(f_{ij}\) indicates if the corresponding detections are linked together. The variable \(\beta_{ij}\) denotes the transition cost given by \(\log P (l_i|l_j)\) for the detection \(l_i,l_j\in L\). The local cost \(\alpha_i\) is the log-likelihood of an intermediate detection being a true positive. For simplicity, we assume that all detections have the same likelihood. This is equivalent to the flow optimization problem, solvable in real-time with k-shortest paths.

Hand Hygiene Activity Classification

So far, we have identified the tracks (i.e., position on the global hospital-unit ground plane) of all pedestrians in the unit. The last step is to detect hand hygiene activity and link it to a specific track. Hand hygiene activity is defined as positive when a person uses a wall-mounted alcohol-based gel dispenser. We then label each pedestrian track as clean or not clean.

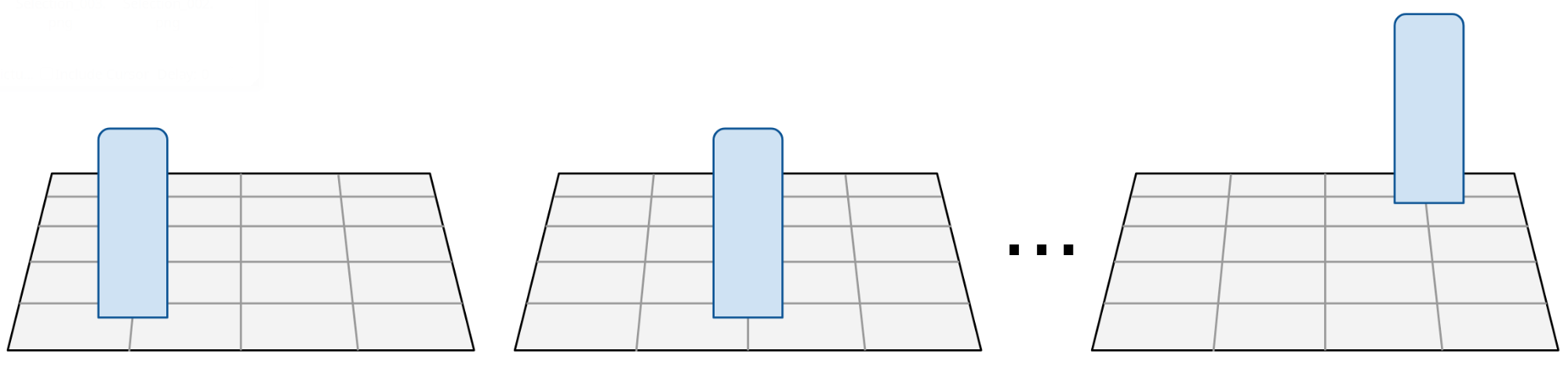

Deployment of sensors in real-world settings is often prone to installation constraints. Whether intentional or not, construction and maintenance technicians install sensors that vary in both angle and position, which meansour model must be robust to such variances so it can work with any sensor viewpoint. Since traditional convolutional neural network (CNNs) are generally not viewpoint invariant, we use a spatial transformer network (STN) instead.

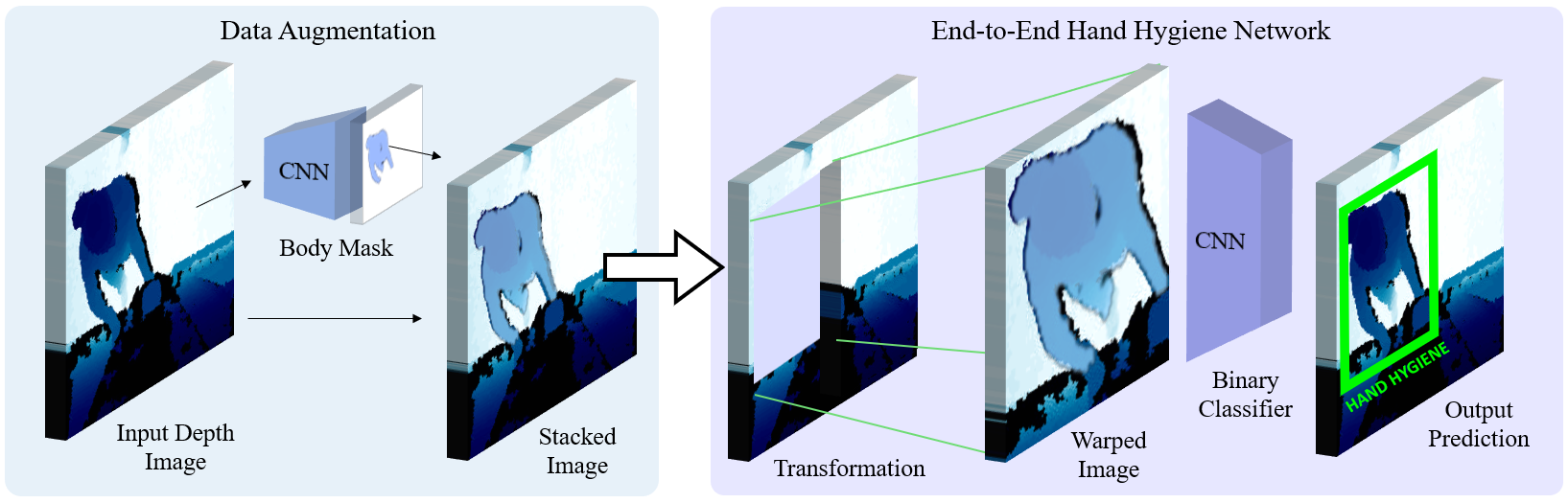

(Left) Data augmentation stage with a person segmentation. (Right) Hand hygiene activity classifier: a spatial transformer network plus a densely connected convolutional network.

The input to the STN is any arbitrary image and the output is a warped image. To help our model learn more quickly, we also provide a person segmentation (i.e., body mask) to the STN. This body mask can be extracted using classical foreground-background techniques or deep learning approaches. The STN warps the image into a learned, “viewpoint-invariant” form. From this warped image, we use a standard CNN (i.e., DenseNet) to perform binary classification of whether someone used the hand hygiene dispenser or not.

Spatio-Temporal Matching

At this point, we still need to combine our set of tracks and a separate set of hand hygiene detections, which introduces two new variables: space and time. For each hand hygiene classifier detection (i.e., dispenser is being used), we must match it to a single track. A match occurs between the classifier and tracker when a track \(\mathcal{T}\) satisfies two conditions:

- Track \(\mathcal{T}\) contains \((x,y)\) points \(\mathcal{P}\) which occur at the same time as the hand hygiene detection event \(\mathcal{E}\), within some temporal tolerance level.

- At least one point \(p \in \mathcal{P}\) is physically nearby the sensor responsible for the detection event \(\mathcal{E}\). This is defined by a proximity threshold around the patient’s door.

If there are multiple tracks that satisfy these requirements, we break ties by selecting the track with the closest \((x, y)\) position to the door. The final output of our model is a list \(T\) of tracks, where each track consists of an ordered list of \((t, x, y, a)\) tuples where \(t\) denotes the timestamp, \(x, y\) denote the 2D ground plane coordinate, and \(a\) denotes the latest action or event label. From \(T\), we can compute the compliance rate or compare with the ground truth for evaluation metrics.

Comparison to Human Auditors & RFID

Today, many hospitals measure hand hygiene compliance using secret shoppers , trained individuals who walk around hospital units and watch if staff wash their hands in secret. A secret shopper could be a nurse, doctor, or even a visitor. We refer to this as a covert observation, as opposed to an overt observation performed by someone openly disclosing their audit. The purpose of covert observations is to minimize the Hawthorne effect (i.e., you change your behavior because someone is watching you). We compared computer vision to multiple auditors standing in fixed locations in the unit and one auditor walking around the unit, and to the use of RFID tags, as discussed above.

Results

RFID produced a lot of false positives and had a low compliance accuracy. It predicted a clean or dirty track correctly only 18% of the time.

One human auditor did much better at 63%. Three people did better yet at 72%. However, our algorithm surpassed even human auditors with a 75% accuracy. This is not too surprising, since the auditors were competing with the “global view” computer vision system. Since the ground truth labels are also annotated by humans, how did the humans observers do worse than the algorithm? The reason is that our ground truth labels were labeled remotely and not in real-time. Remote annotators had access to all sensors and could play the video forward and backward in time to ensure their annotations are correct. In-person auditors did not have “access” to all sensors and they could not replay events in time.

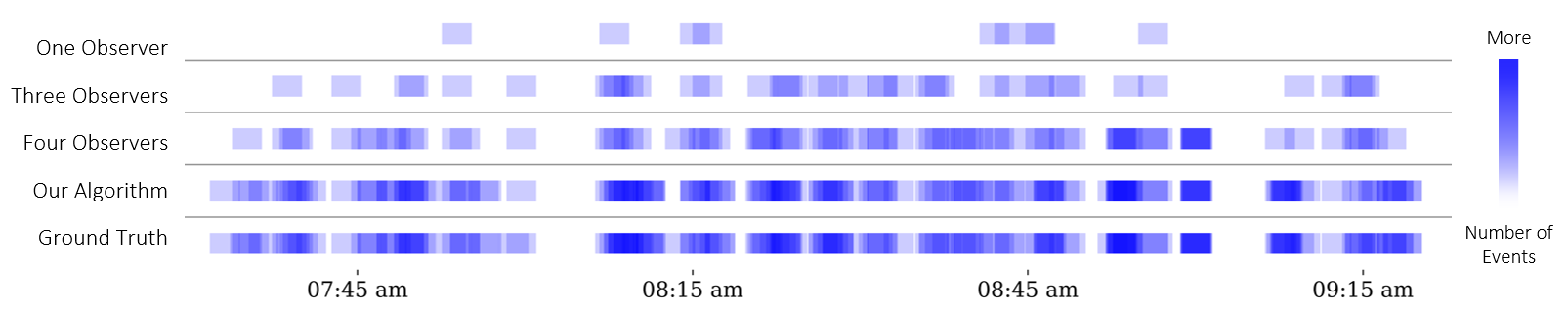

Hand hygiene detections over time. Blue squares indicate someone using a hand hygiene dispenser. Darker blue indicates more simultaneous events. The ground truth is shown at the bottom. In general, more white space is bad.

Numbers aside, a more interesting result is a visual one. The image above shows how infrequently the in-person auditors detect hand hygiene activity. Notice all the white space? If you look at the ground truth row, there is usually no white space. That means the observers are missing a lot of hand hygiene events. This is often due to observers getting distracted: they may doze off, look at unrelated activity elsewhere in the unit, or simply just not see hand hygiene events occuring.

Spatio-temporal heatmap of people walking in the intensive care unit. Yellow/red colors indicate more people standing/walking in that area.

We conclude with one final visualization. The animation above shows a top view of the hospital unit. Because we can track people across the entire unit, we know their specific (x,y,z) position pretty much all the time. We plotted each point and created a heatmap over time. This type of spatial analytics can be useful for identifying traffic patterns and potentially trace the spread of disease. Areas that are always yellow/red indicate crowded spaces. These spaces are usually at hallway intersections or immediately outside patient rooms. If you look carefully, you can spot our stationary auditors in red.

Future Directions

We’ve shown how computer vision and deep learning can be used to automatically monitor hand hygiene in hospitals. At the Stanford Partnership in AI-Assisted Care, hand hygiene is just one use case of computer vision in healthcare. We are also developing computer vision systems to monitor patient mobility levels, analyze the quality of surgical procedures, and check for anomalies in senior living. We hope this work sheds new light on the potential and impact of AI-assisted healthcare.

References

Viewpoint Invariant Convolutional Networks for Identifying Risky Hand Hygiene Scenarios. M. Guo, A. Haque, S. Yeung, J. Jopling, L. Downing, A. Alahi, B. Campbell, K. Deru, W. Beninati, A. Milstein, L. Fei-Fei. Workshop on Machine Learning for Health (ML4H), Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Long Beach, CA, December 2017.

Towards Vision-Based Smart Hospitals: A System for Tracking and Monitoring Hand Hygiene Compliance. A. Haque, M. Guo, A. Alahi, S. Yeung, Z. Luo, A. Rege, A. Singh, J. Jopling, L. Downing, W. Beninati, T. Platchek, A. Milstein, L. Fei-Fei. Machine Learning in Healthcare Conference (MLHC), Boston, MA, USA, August 2017.

Vision-Based Hand Hygiene Monitoring in Hospitals. S. Yeung, A. Alahi, Z. Luo, B. Peng, A. Haque, A. Singh, T. Platchek, A. Milstein, L. Fei-Fei. American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) Annual Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, November 2016.