My tennis coach often used to say that “the only opponent that returns all your shots is a wall” when encouraging me to practice against a tennis wall by myself. Learning complex skills requires repetition: try, correct, then try again. Regardless of the skill, from switching barre chords on a guitar, doing a backflip, or fixing your running gait, limited access to expert instruction is rarely sufficient to learn a complex skill. Augmenting expert instruction with practice is key to improvement. Could robots similarly benefit from practicing autonomously when learning complex skills?

Beyond the anthropomorphic motivation presented above, improving autonomy for robots addresses the long-standing challenge of lack of large robotic interaction datasets. While learning from data collected by experts (“demonstrations”) can be effective for learning complex skills, human-supervised robot data is very expensive to collect. One of the largest robotic interaction datasets used for SayCan / RT-1 contains 130,000 demonstrations of tasks such as “pick up the soda can”, collected over 17 months using 13 human-supervised robots. What if these robots were collecting data autonomously? A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that 13 robots interacting autonomously over 17 months would collect over 17 million trajectories1, as much as 100x more interaction data!

How can we build autonomous robots that can meaningfully interact with their environments and improve from such interaction? Reinforcement learning (RL) offers a natural framework to construct such systems, where agents can learn from trial-and-error. And indeed, RL has been used to develop proficient robotic systems, from manipulation to locomotion. Unfortunately, training robotic systems using RL still requires extensive human supervision during training, as shown in the figure below:

A human has to reset the environment before every trial of the task for current RL algorithms to successfully learn a task. Indeed such supervision is expensive, inhibiting robots from learning and improving autonomously. Scripted behaviors to automate resetting the environment are often brittle, as resetting the environment can be as hard as the task itself. For example, learning how to open the door requires closing the door to reset the environment which can be just as hard for the robot. Effectively minimizing the need for human supervision to reset environments after every trial is critical for collecting the massive data sets necessary for training robots.

This blog post discusses three works in this vein: (a) EARL demonstrates that current RL algorithms struggle without frequent human resets, and presents a possible explanation for this phenomenon, (b) MEDAL presents a RL algorithm that can learn efficiently while being autonomous and (c) Self-Improving Robots builds upon MEDAL to present a real-robot system that can improve itself from autonomous interaction with the environment.

EARL: RL algorithms fail without frequent resetting of the environment

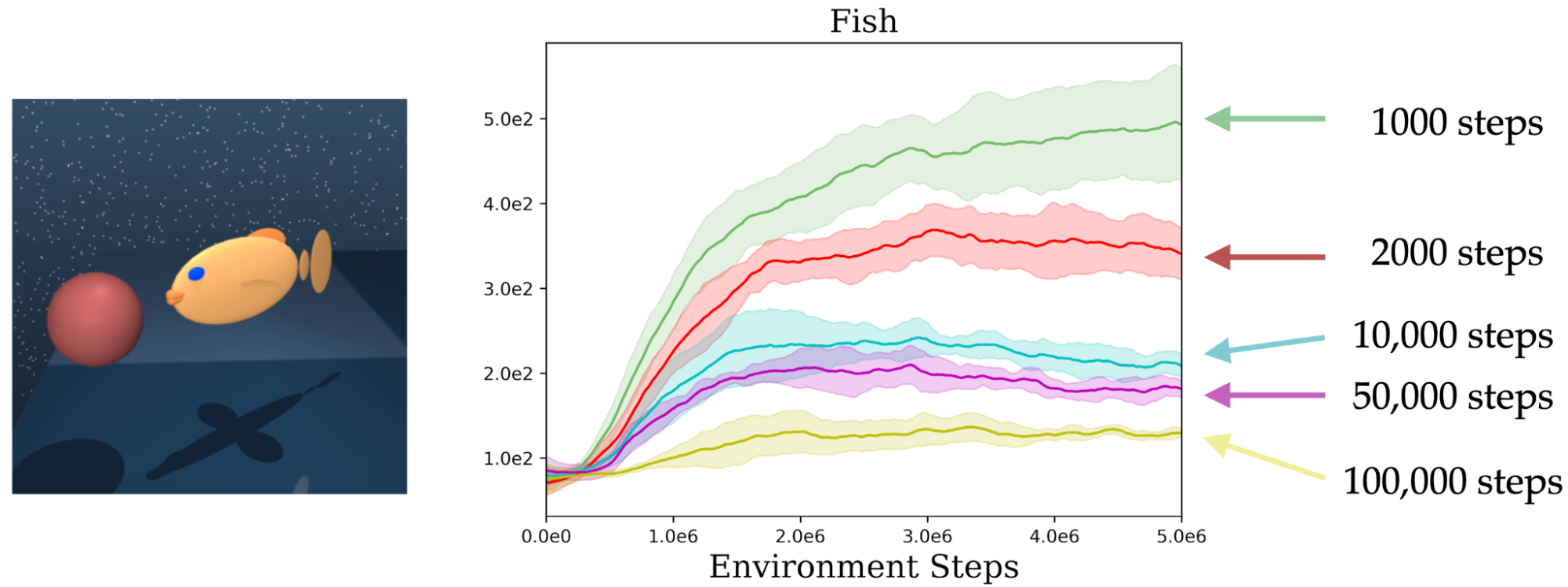

Consider the task of learning to navigate the yellow fish to the red goal in the figure above. A typical RL algorithm would approach this in an episodic manner, i.e., an agent attempts the task for a fixed number of steps before giving up if unsuccessful. Critically, between each episode, the environment needs to be reset before the agent can re-try the task. But what happens if, instead of resetting the environment, we simply allow the agent to continue acting? To test this, we set up an experiment measuring the performance of the agent as the length of the episode becomes longer. We observe that the learned policy gets substantially worse as the environment is reset less frequently. This presents the crux of our problem: a typical RL algorithm needs to retry the task repeatedly several times, and resetting the environment requires consistent human supervision throughout training (also noted in previous works).

Why does resetting the environment less frequently lead to worse policies? The answer is that when the environment is not reset frequently, the agent, which is trained to maximize a reward function, tends to loiter around high reward states. This results in insufficient exploration of the entire space and, consequently, less data for learning a competent policy. However, frequently resetting the environment is not feasible in the real world. To aid the design of algorithms suitable for learning in the real world, we proposed the autonomous reinforcement learning problem, wherein an agent is tasked with learning an effective policy in an environment with minimal repeated resetting. We introduced a benchmark of challenging simulated environments to evaluate performance without repeated interventions for environment resets. We find that existing RL algorithms struggle on these benchmarks, leaving a large room for improvement.

MEDAL: What if we learn a policy to undo the task?

So how do we train agents without repeated human interventions? The key idea is to learn to reset the environment such that humans do not need to repeatedly intervene. Specifically, the agent learns a forward policy to do the task and a backward policy to undo the task. The two policies are chained together one after the other, to enable the agent to train autonomously with minimal human interventions. What should the backward policy optimize for? It might seem natural to train a backward policy to reach the initial state distribution so that the forward policy can try the task from the initial state distribution repeatedly. Can we learn a backward policy that helps the forward policy learn more efficiently?

To successfully learn how to task-solving forward policy, robot learning often needs a small set of expert demonstrations on “how to solve the task”. Finding an initial path to the goal can be extremely time consuming (i.e. the “exploration problem”), and expert demonstrations can substantially speed up learning by counteracting this exploration challenge. Our key insight is that if such expert demonstrations are available, (a) it can be easier to learn a backward policy that reaches any of the states that the expert visited in the demonstrations, in contrast to just the initial state distribution and (b) expert states form a more effective distribution of starting states for learning a forward policy, as the agent to try the task from a variety of states ranging from easy to hard. The forward policy can learn to solve the task from states closer to the goal (“easy initial states”), and use the successes to learn from starting states farther away from the goal (“hard initial states”). This serves as the motivation for Matching Expert Distributions for Autonomous Learning (MEDAL), where the agent learns a forward policy to maximize the task rewards and a backward policy learns to uniformly cover the states visited by an expert, without any additional engineered reward functions to train the backward policy. And indeed, MEDAL substantially improves both the learning efficiency and the final performance of the learned policies.

Other works to check out: VaPRL, R3L, Leave No Trace

How do we put together a self-improving robotic system?

Now that we have an efficient learning algorithm without repeated human interventions, we can return to our objective of building self-improving robots! Real-world robot learning presents two additional challenges beyond the lack of supervision for resetting environments: first, low-dimensional states such as object coordinates are expensive to engineer for every task (requires object detectors, calibration etc) and robotic systems need to learn directly from raw sensory data such as image inputs and second, the real world does not provide reward labels and robots need to learn without engineered task-specific reward functions.

To address these issues, we propose MEDAL++ to adapt and improve MEDAL for self-improving robotic systems. To train our policies efficiently from pixel inputs, we use random crop and shift augmentations to regularize the learning. Importantly, how do we learn without task-rewards? Expert demonstrations come to the rescue again! We can use the terminal states in expert demonstrations as proxy for what goal states look like, and reward the forward policy to reach states “similar” to those states. The similarity is measured by an adversarially trained classifier, based on the idea that visual similarity increases as the robot gets closer to the goal. Thus, the expert demonstrations serve as supervision to train both the forward policy and the backward policy. We use MEDAL++ to train a Franka arm autonomously to perform several manipulation tasks, examples shown in the figure below. Starting with only ~50 expert demonstrations, the robot arm could improve the success rate between 30-70% through (mostly) autonomous practice over the course of ~20 hours (with less than 50 interventions to reset the environment!). More details can be found in the paper and on the website. Overall, MEDAL++ allows for a learning paradigm where an expert provides instruction through a small number of demonstrations, and the robot can practice autonomously thereafter.

Are we there yet?

These are quite exciting times for scaling robot learning, and collecting/training on large datasets is at the heart of it. Recent works have started leveraging internet-scale sources of data (such as YouTube) to augment robot learning. While these sources will be important to form representations of the world, embodied robot data is critical to learn complex skills as it carries information about robot-environment interaction without any domain shift. And, as this article discusses, it can be scaled a LOT more through our framework for autonomous RL.

However, our work only begins to tackle this challenging problem and there are several questions and avenues for improvement:

Shared Autonomy: While we emphasized autonomy and reducing the need for resetting environments in this article, human supervision is indeed extremely useful for robot learning. However, using it to reset the environment repeatedly does not seem to be the best use of this supervision. What is a scalable and effective allocation amongst different forms of human supervision, such as resetting environments, labeling rewards or expert demonstrations of the task?

Handling Irreversibility: Inevitably, robotic agents will encounter irreversible states where humans need to intervene, for example, pushing a mug out of reach of a robot arm. We made an initial attempt with PAINT as a framework to learn when to ask for help from a human, but lots of room to better use human supervision!

Autonomous Deployment: Robots deployed autonomously will inevitably encounter novel states not present in the training data. Can they recover autonomously if they get stuck (for example, a last mile delivery bot stuck in a pothole) and continue to optimize their objectives? We propose this problem setting in our work on single-life RL, along with some initial solutions (and large room for improvement!).

Better Benchmarks: EARL is a small benchmark with lots of challenges of autonomous RL still not covered (for example, irreversible states). Creating more diverse and expressive environments could better aid algorithmic development, and understanding the tradeoffs between forms and amounts of supervision.

Closing off: To achieve broadly capable robots that can operate autonomously in unstructured environments such as kitchens, homes and offices, it may be useful to learn autonomously in the real world directly. It is worthwhile to think about what it would take for robots to run 24x7, collecting data in diverse environments to truly fulfill the vision. I hope this post sheds some light on the challenges and solutions towards this goal, and we can soon move towards a world with greater robot uptime :)

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Chelsea Finn for feedback on this post, and support through the many projects. I would like to acknowledge valuable suggestions and proofreading from many friends: Rohan Taori, Annie Chen, Kaylee Burns, Rose Wang, Eric Mitchell, Sidd Karamcheti, Kanishk Gandhi, Allan Zhou. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the editorial feedback from Megha Srivastava and Jacob Schreiber in making the post user-friendly.

-

13 (robots) * 17 (months) * 30 (days / month) * 24 (hrs / day) * 60 (min / hr) * 60 (seconds / min) * 3 (control frequency) / 100 (steps / trajectory) = 17,184,960 trajectories ↩