In recent years, the real-world impact of machine learning (ML) has grown in leaps and bounds. In large part, this is due to the advent of deep learning models, which allow practitioners to get state-of-the-art scores on benchmark datasets without any hand-engineered features. Given the availability of multiple open-source ML frameworks like TensorFlow and PyTorch, and an abundance of available state-of-the-art models, it can be argued that high-quality ML models are almost a commoditized resource now. There is a hidden catch, however: the reliance of these models on massive sets of hand-labeled training data.

These hand-labeled training sets are expensive and time-consuming to create — often requiring person-months or years to assemble, clean, and debug — especially when domain expertise is required. On top of this, tasks often change and evolve in the real world. For example, labeling guidelines, granularities, or downstream use cases often change, necessitating re-labeling (e.g., instead of classifying reviews only as positive or negative, introducing a neutral category). For all these reasons, practitioners have increasingly been turning to weaker forms of supervision, such as heuristically generating training data with external knowledge bases, patterns/rules, or other classifiers. Essentially, these are all ways of programmatically generating training data—or, more succinctly, programming training data.

We begin by reviewing areas of ML that are motivated by the problem of labeling training data, and then describe our research on modeling and integrating a diverse set of supervision sources. We also discuss our vision for building data management systems for the massively multi-task regime with tens or hundreds of weakly supervised dynamic tasks interacting in complex and varied ways. Check out the our research blog for detailed discussions of these topics and more!

How to Get More Labeled Training Data? A Review

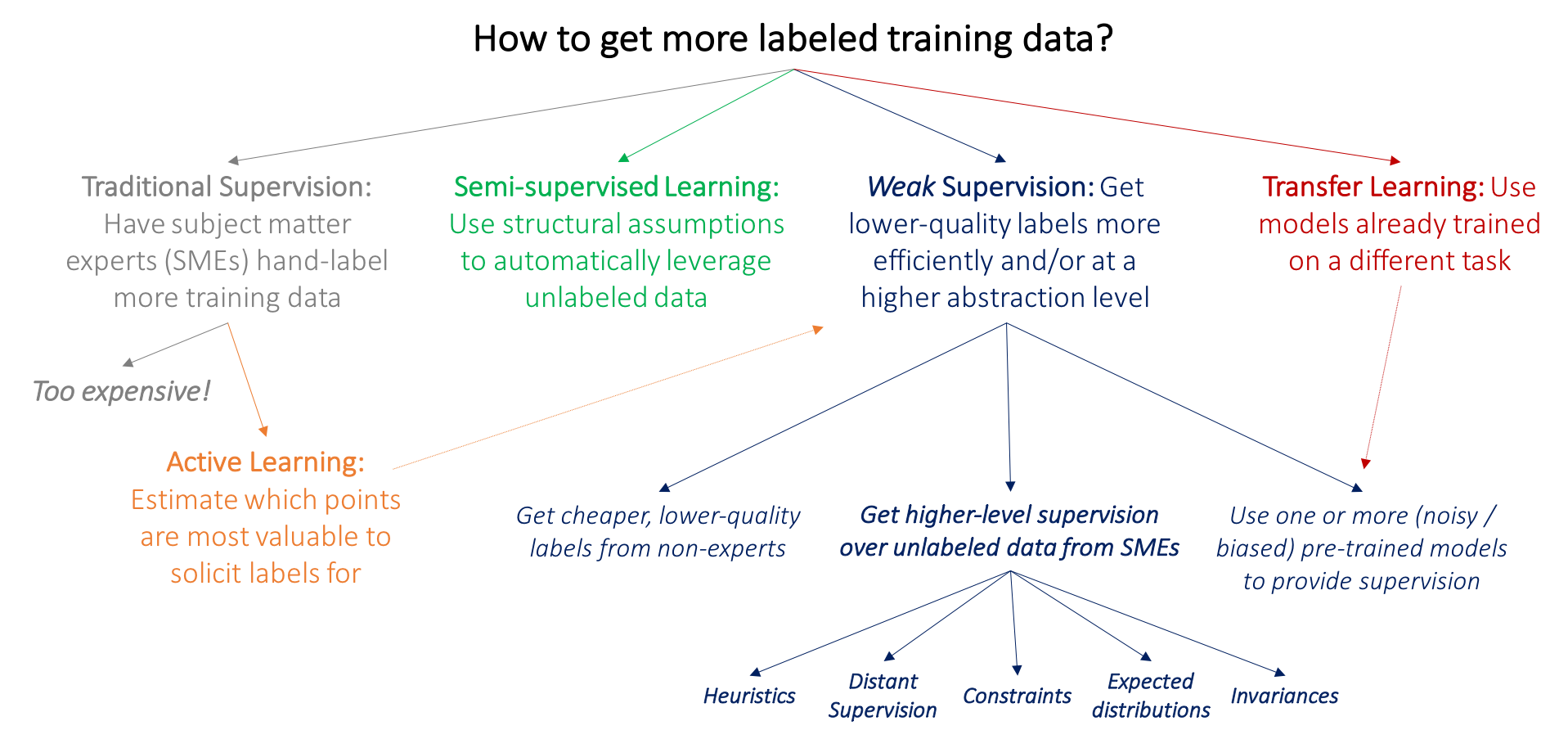

Many traditional lines of research in ML are similarly motivated by the insatiable appetite of deep learning models for labeled training data. We start by drawing the core distinction between these other approaches and weak supervision at a high-level: weak supervision is about leveraging higher-level and/or noisier input from subject matter experts (SMEs).

The key problem with the currently predominant approach of just having SMEs directly label a large amount of data is that it is expensive: for example, it is much harder to get large datasets for research in medical imaging — unlike grad students, radiologists don’t generally accept payment in burritos and free T-shirts! Thus, many well-studied lines of work in ML are motivated by the bottleneck of getting labeled training data:

- In active learning, the goal is to make use of SMEs more efficiently by having them label data points which are estimated to be most valuable to the model (for a good survey, see (Settles 2012)). In the standard supervised learning setting, this means selecting new data points to be labeled. For example, we might select mammograms that lie close to the current model decision boundary, and ask radiologists to label only these. However, we could also just ask for weaker supervision pertinent to these data points, in which case active learning is perfectly complementary with weak supervision; as one example of this, see (Druck, Settles, and McCallum 2009).

- In the semi-supervised learning setting, the goal is to use both a small labeled training set and a much larger unlabeled data set. At a high level, we then use assumptions about smoothness, low dimensional structure, or distance metrics to leverage the unlabeled data (either as part of a generative model, as a regularizer for a discriminative model, or to learn a compact data representation); for a good survey see (Chapelle, Scholkopf, and Zien 2009). Broadly, rather than soliciting more input from SMEs, the idea in semi-supervised learning is to leverage domain and task-agnostic assumptions to exploit the unlabeled data that is often cheaply available in large quantities. More recent methods use generative adversarial networks (Salimans et al. 2016), heuristic transformation models (Laine and Aila 2016), and other generative approaches to effectively help regularize decision boundaries.

- In a typical transfer learning setting, the goal is to take one or more models already trained on a different dataset and apply them to our dataset and task; for a good overview see (Pan and Yang 2010). For example, we might have a large training set for tumors in another part of the body and classifiers trained on this set and wish to apply these to our mammography task. A common transfer learning approach in the deep learning community today is to “pre-train” a model on one large dataset, and then “fine-tune” it on the task of interest. Another related line of work is multi-task learning, where several tasks are learned jointly (Caruna 1993; Augenstein, Vlachos, and Maynard 2015).

The above paradigms potentially allow us to avoid asking our SME collaborators for additional training labels. However, the need for labeling some data is unavoidable. What if we could ask them for various types of higher-level, or otherwise less precise, forms of supervision, which would be faster and easier to provide? For example, what if our radiologists could spend an afternoon specifying a set of heuristics or other resources, that, if handled properly, could effectively replace thousands of training labels?

Injecting Domain Knowledge into AI

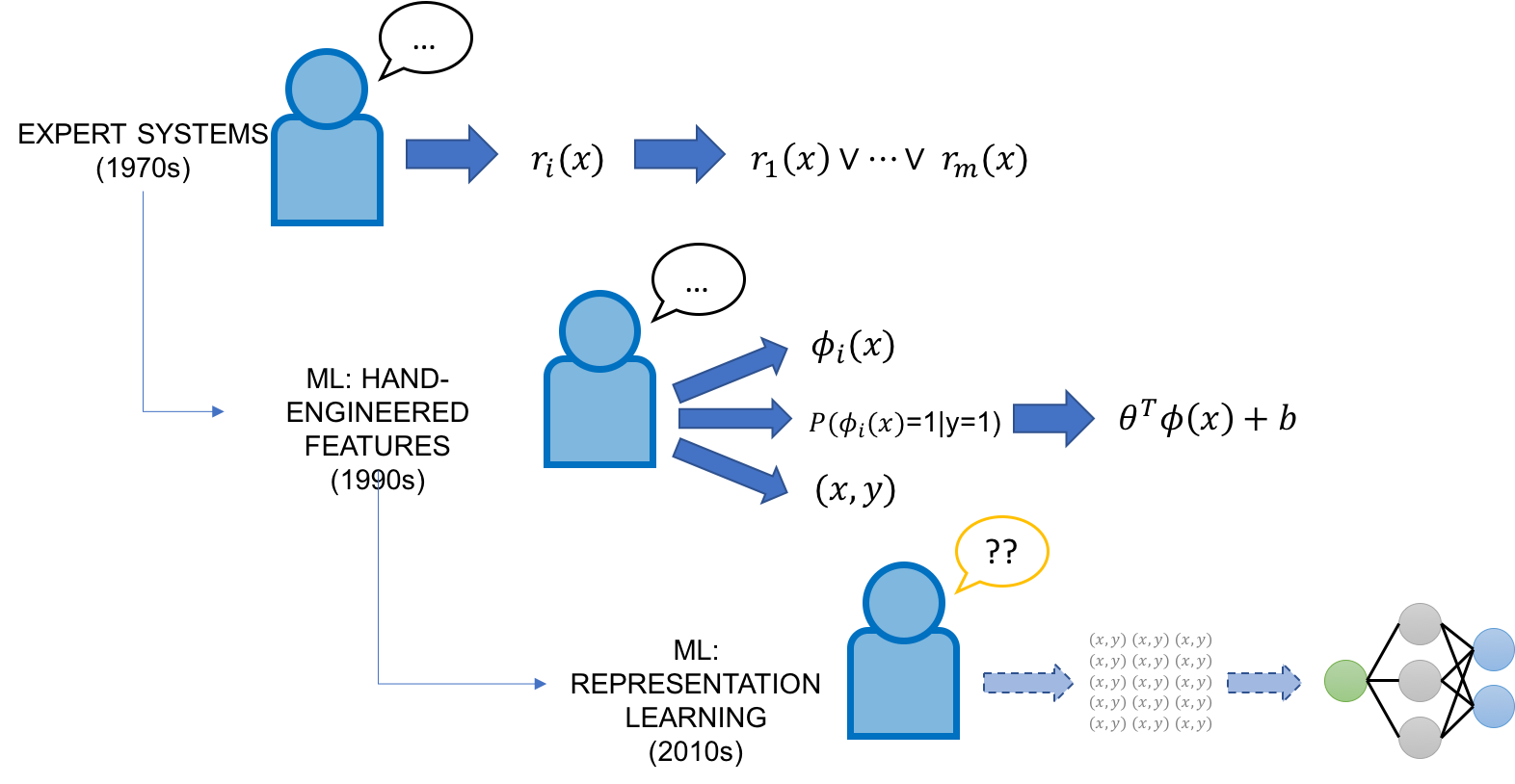

From a historical perspective, trying to “program” AI (i.e., inject domain knowledge) is nothing new — the main novelty in asking this questions now is that AI has never before been so powerful while also being such a “black box” in terms of interpretability and control.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, the focus in AI was on expert systems, which combined manually-curated knowledge bases of facts and rules from domain experts with inference engines to apply them. In the 1990’s, ML began to take off as the vehicle for integrating knowledge into AI systems, promising to do so automatically from labeled training data in powerful and flexible ways. Classical (non-representation-learning) ML approaches generally had two ports of domain expert input. First, these models were generally of much lower complexity than modern ones, meaning that smaller amounts of hand-labeled data could be used. Second, these models relied on hand-engineered features, which provided a direct way to encode, modify, and interact with the model’s base representation of the data. However, feature engineering was and still is generally considered a task for ML experts, who often would spend entire PhDs crafting features for a particular task.

Enter deep learning models: due to their impressive ability to automatically learn representations across many domains and tasks, they have largely obviated the task of feature engineering. However, they are for the most part complete black boxes, with little control for the average developer other than labeling massive training sets and tweaking the network architecture. In many senses, they represent the opposite extreme of the brittle but easily-controllable rules of old expert systems — they are flexible but hard to control. This leads us back to our original question from a slightly different angle: How do we leverage our domain knowledge or task expertise to program modern deep learning models? Is there any way to combine the directness of the old rules-based expert systems with the flexibility and power of these modern ML methods?

Code as Supervision: Training ML by Programming

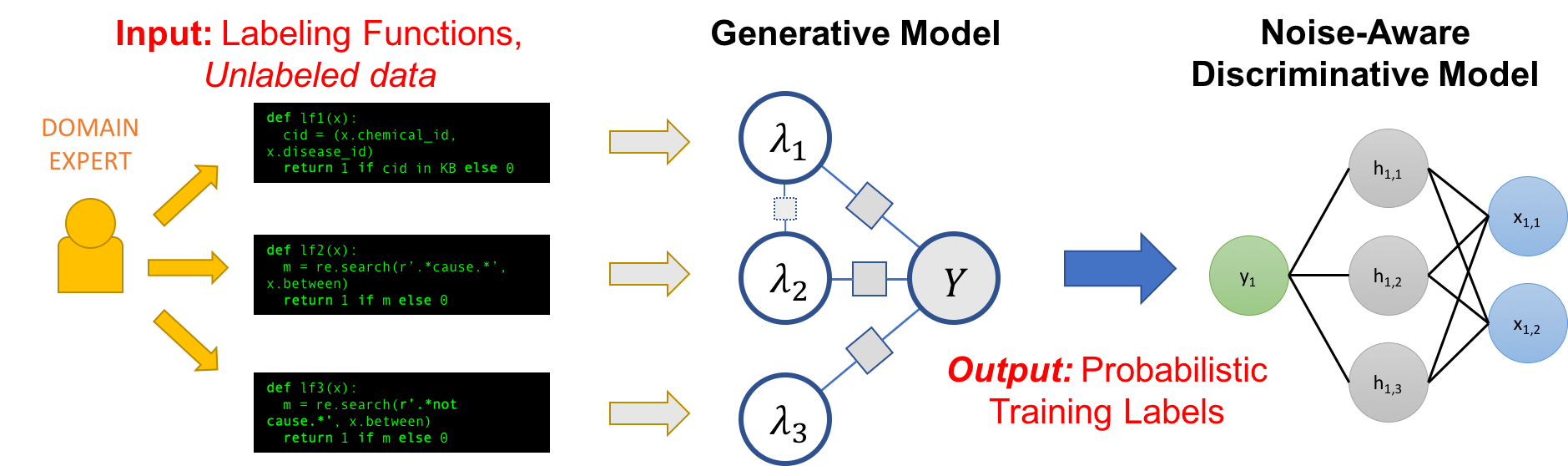

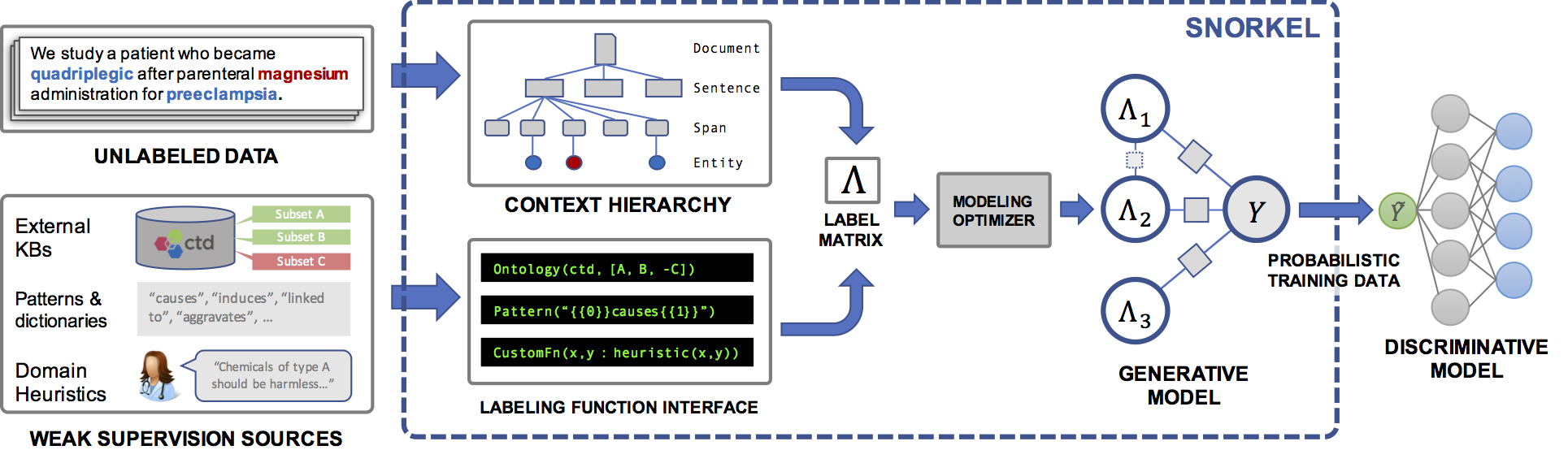

Snorkel is a system we have built to support and explore this new type of interaction with ML. In Snorkel, we use no hand-labeled training data, but instead ask users to write labeling functions (LFs), black-box snippets of code which label subsets of unlabeled data.

We could then use a set of such LFs to label training data for our ML model. Since labeling functions are just arbitrary snippets of code, they can encode arbitrary signals: patterns, heuristics, external data resources, noisy labels from crowd workers, weak classifiers, and more. And, as code, we can reap all the other associated benefits like modularity, reusability, debuggability. If our modeling goals change, for example, we can just tweak our labeling functions to quickly adapt!

One problem, of course, is that the labeling functions will produce noisy outputs which may overlap and conflict, producing less-than-ideal training labels. In Snorkel, we de-noise these labels using our data programming approach, which comprises three steps:

- We apply the labeling functions to unlabeled data.

- We use a generative model to learn the accuracies of the labeling functions without any labeled data, and weight their outputs accordingly. We can even learn the structure of their correlations automatically.

- The generative model outputs a set of probabilistic training labels, which we can use to train a powerful, flexible discriminative model (such as a deep neural network) that will generalize beyond the signal expressed in our labeling functions.

This whole pipeline can be seen as providing a simple, robust, and model-agnostic approach to “programming” an ML model!

Labeling Functions

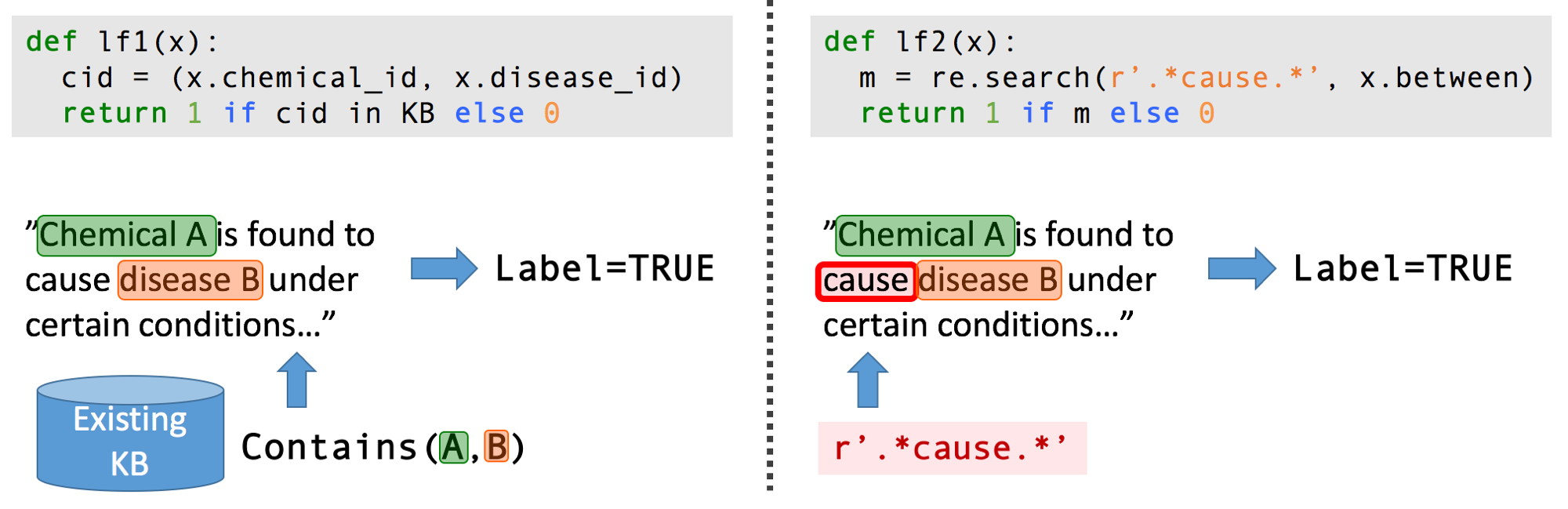

Extracting structured information from the biomedical literature is one of the applications that motivates us most: volumes of useful information are effectively locked away in the dense unstructured text of millions of scientific articles. We’d like to extract it all using machine learning, so that our bio-collaborators could use it to do things like diagnose genetic diseases.

Consider the task of extracting mentions of a certain chemical-disease relationship from the scientific literature. We may not have a large enough (or any) labeled training dataset for this task. However, in the biomedical space there is a profusion of curated ontologies, lexicons, and other resources, which include various ontologies of chemical and disease names, databases of known chemical-disease relations of various types, etc., which we can use to provide weak supervision for our task. In addition, we can come up with a range of task-specific heuristics, regular expression patterns, rules-of-thumb, and negative label generation strategies with our bio-collaborators.

Generative Model as an Expressive Vehicle

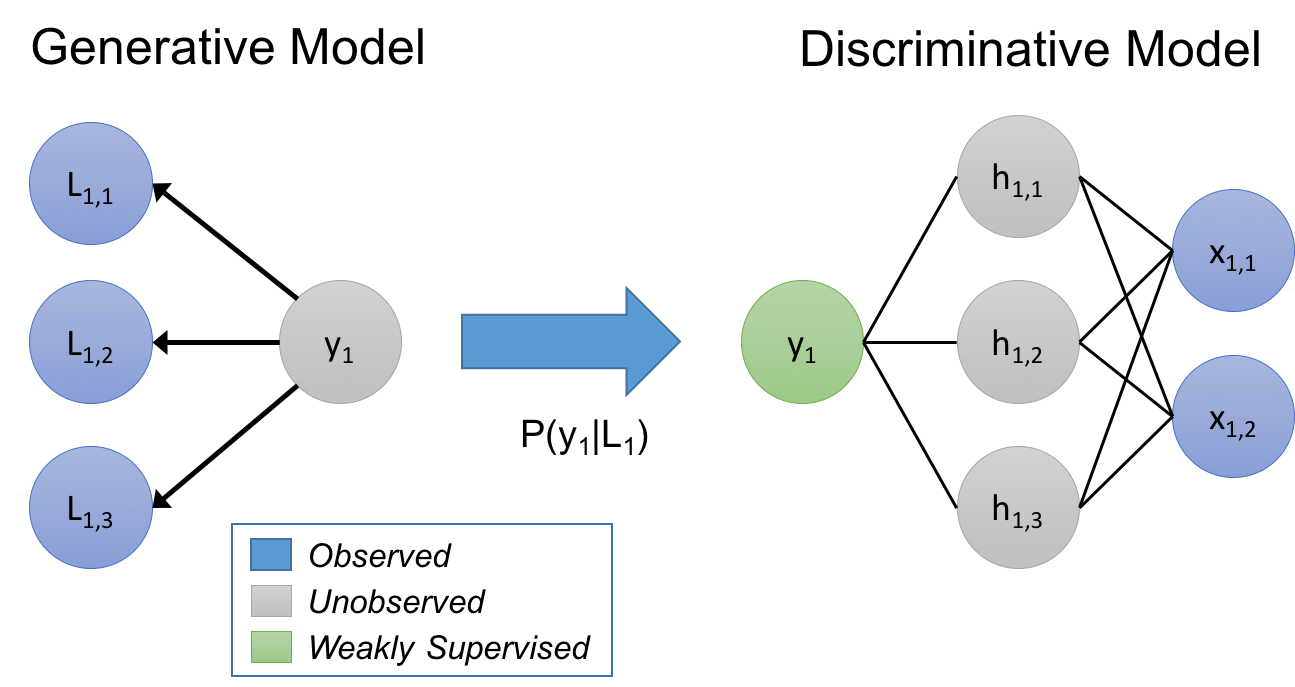

In our approach, we consider the labeling functions as implicitly describing a generative model. To give a quick refresher: given data points x, having unknown labels y that we want to predict, in a discriminative approach we model P(y|x) directly, while in a generative approach we model P(x,y) = P(x|y)P(y). In our case, we’re modeling a process of training set labeling, P(L,y), where L are the labels generated by the labeling functions for objects x, and y are the corresponding (unknown) true labels. By learning a generative model, and directly estimating P(L|y), we are essentially learning the relative accuracies of the labeling functions based on how they overlap and conflict (note, we don’t need to know y!)

We use this estimated generative model over the labeling functions to train a noise-aware version of our end discriminative model. To do so, the generative model infers probabilities over the unknown labels of the training data, and we then minimize the expected loss of the discriminative model with respect to these probabilities.

Estimating the parameters of these generative models can be quite tricky, especially when there are statistical dependencies between the labeling functions used (either user-expressed or inferred). In our work, we show that given enough labeling functions, we can get the same asymptotic scaling as with supervised methods (except in our case, of course, with respect to unlabeled data). We also study how we can learn correlations among the labeling functions without using labeled data and how it can improve performance significantly.

Notes from Snorkel in the Wild!

In our recent paper on Snorkel, we find that in a variety of real-world applications, this new approach to interacting with modern ML models works very well! Some highlights include:

-

In a user study, conducted as part of a two-day workshop on Snorkel hosted by the Mobilize Center, we compared the productivity of teaching SMEs to use Snorkel, versus spending the equivalent time just hand-labeling data. We found that they were able to build models not only 2.8x faster but also with 45.5% better predictive performance on average.

-

On two real-world text relation extraction tasks—in collaboration with researchers from Stanford, the U.S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration—and four other benchmark text and image tasks, we found that Snorkel leads to an average 132% improvement over baseline techniques.

-

We explored the novel tradeoff space of how to model the user-provided labeling functions, leading to a rule-based optimizer for accelerating iterative development cycles.

Next Steps: Massively Multi-Task Weak Supervision

Various efforts in our lab are already underway to extend the weak supervision interaction model envisioned in Snorkel to other modalities such as richly-formatted data and images, supervising tasks with natural language and generating labeling functions automatically! On the technical front, we’re interested in both extending the core data programming model at the heart of Snorkel, making it easier to specify labeling functions with higher-level interfaces such as natural language, as well as combining with other types of weak supervision such as data augmentation.

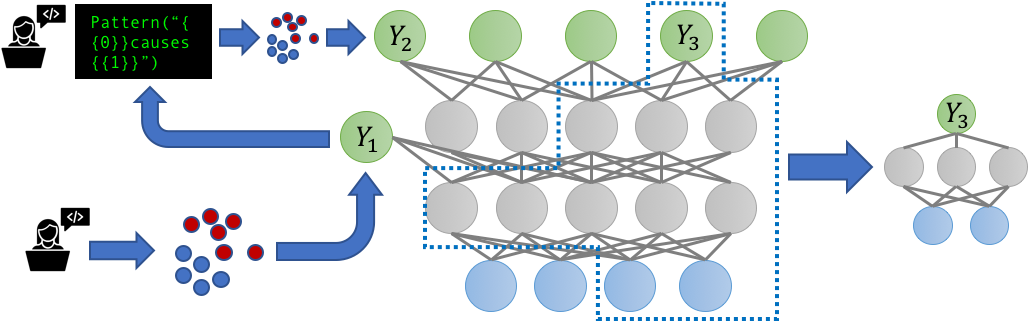

The increasing prevalence of multi-task learning (MTL) scenarios also invites the question: what happens when our noisy, possibly correlated label sources now label multiple related tasks? Can we benefit by modeling the supervision for these tasks jointly? We tackle these questions in a new multitask-aware version of Snorkel, Snorkel MeTaL, which can support multi-task weak supervision sources that provide noisy labels for one or more related tasks.

One example we consider is the setting of label sources with different granularities. For example, suppose we are aiming to train a fine-grained named entity recognition (NER) model to tag mentions of specific types of people and locations, and we have some noisy labels that are fine-grained—e.g. Labeling “Lawyer” vs. “Doctor” or “Bank” vs. “Hospital”—and some that are coarse-grained, e.g. labeling “Person” vs. “Location”. By representing these sources as labeling different hierarchically-related tasks, we can jointly model their accuracies, and reweight and combine their multi-task labels to create much cleaner, intelligently aggregated multi-task training data that improves the end MTL model performance.

We believe that the most exciting aspects of building data management systems for MTL will revolve around handling what we refer to as the massively multi-task regime, where tens to hundreds of weakly-supervised (and thus highly dynamic) tasks interact in complex and varied ways. While most MTL work to date has considered tackling at most a handful of tasks, defined by static hand-labeled training sets, the world is quickly advancing to a state where organizations — whether large companies, academic labs, or online communities—maintain tens to hundreds of weakly-supervised, rapidly changing, and interdependent modeling tasks. Moreover, because these tasks are weakly supervised, developers can add, remove, or change tasks (i.e. training sets) in hours or days, rather than months or years, potentially necessitating retraining the entire model.

In a recent paper, we outlined some initial thoughts in response to the above questions, envisioning a massively multi-task setting where MTL models effectively function as a central repository for training data that is weakly labeled by different developers, and then combined in a central “mother” multi-task model. Regardless of exact form factor, it is clear that there is lots of exciting progress for MTL techniques ahead—not just new model architectures, but also increasing unification with transfer learning approaches, new weakly-supervised approaches, and new software development and systems paradigms.

We’ll be continuing to post our thoughts and code at snorkel.stanford.edu — feedback is always welcome!