A team of aerial and terrestrial robots is sent to analyze previously unexplored terrain by taking photographs and soil samples. Only the aerial robots — drones — can obtain high quality images of tall structures. Imagine that, instead of flying directly from the mission hub to their respective destinations, the drones docked on the ground vehicles for segments of their routes and flew off for a short time to capture some data before swiftly docking back on to a (potentially different) vehicle. Drones are more energy-constrained and sensitive to atmospheric disturbances than their terrestrial counterparts. With such coordination, we could improve energy-efficiency and allow for broader coverage and longer missions.

We are interested in the planning and real-time execution of routes for autonomous vehicles, in settings where the vehicle can use multiple modes of transportation (through other vehicles in the area). The transportation options are updated dynamically and not known in advance. We design a planning and control framework for judiciously choosing transit options and making the corresponding connections in time. The GIF above shows a qualitative example using real GPS data from north San Francisco, in which drones can land on certain cars. A longer, annotated video is available on YouTube.

Dynamic Real-time Multimodal Routing (DREAMR)

The same methodology used for the coordinated exploration problem above can also be applied to package delivery. Alphabet’s Wing has already rolled out in Australia, and diverse companies like Ford and UPS have been interested in augmenting delivery drones through ground vehicles. By piggybacking on ground vehicles like cars or trucks in addition to flying en route to their own destination, drones can significantly extend their effective ranges. There is a whole host of relevant multi-robot applications like search-and-rescue and wildlife monitoring that could benefit from such coordination during routing.

To formalize our use cases of interest, we introduce the problem class of Dynamic Real-time Multimodal Routing (DREAMR). Ultimately, we are interested in routing the autonomous agent, and in doing so in real-time rather than on request. The agent has access to a dynamic or rapidly-changing set of transit options, in which it can use multiple modes of transportation (we refer to this as multimodal), in addition to moving by itself. In this post, we will explain how DREAMR problems are difficult and propose an algorithmic framework to solve them. For simplicity, we will continue to use the example of drones planning over car routes, as in figure 1.

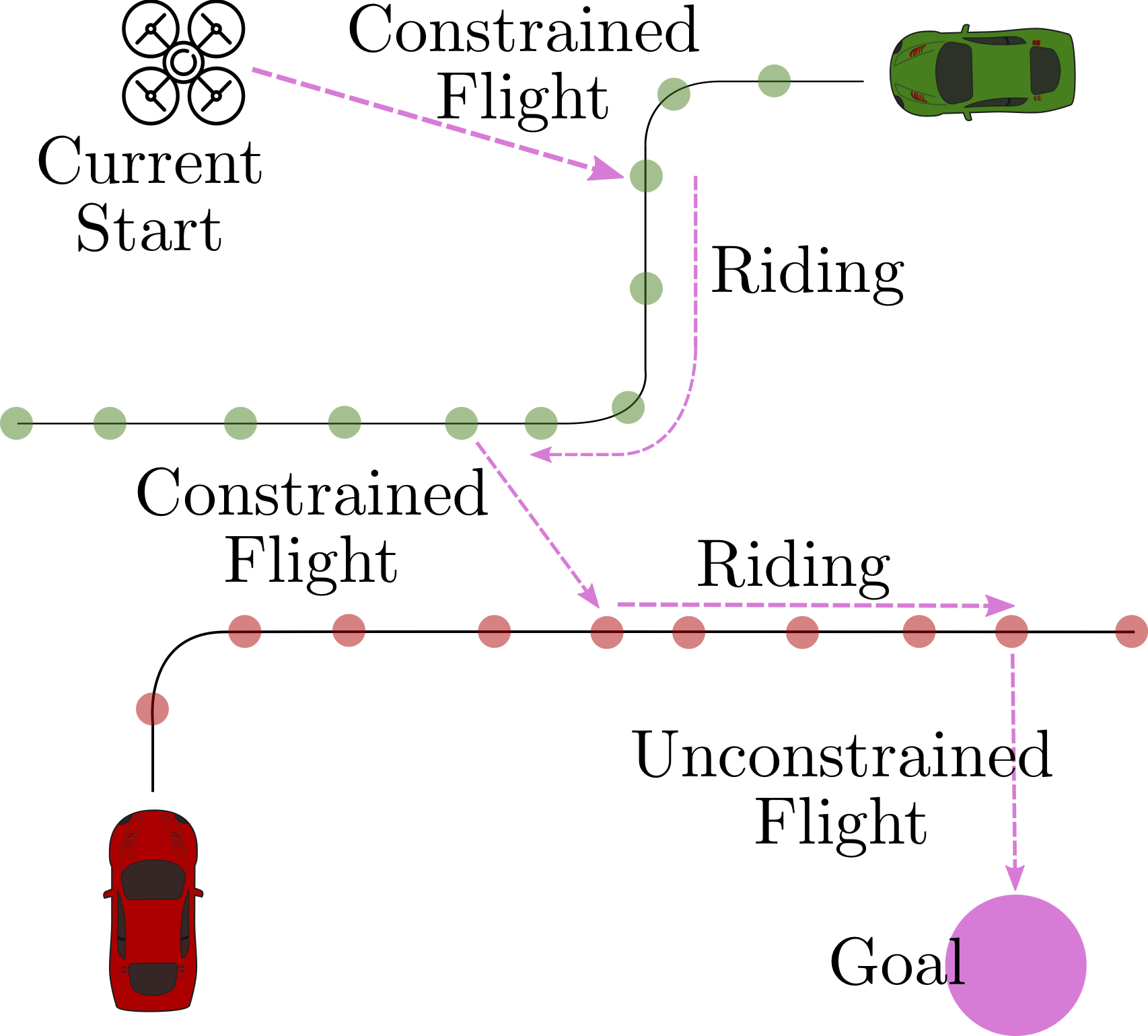

Fig. 1: The DREAMR problem requires real-time decisions for an agent to traverse a network of dynamic transit routes. The example of drones riding on cars is purely illustrative; our framework permits other agent dynamics and transit route properties.

Understanding DREAMR

Problems like DREAMR are quite ubiquitous in everyday life. One example is that of public transit planning with, say, Google Maps. In areas with many and varied transit options, Maps provides numerous solutions for commuting between two locations, which involve walking to some stop, using a mode of transportation for some distance, and then either walking the rest of the way or transferring to a potentially different mode of transportation, and so on. Indeed, there has been extensive work on such multimodal route planning for humans with public transit (this master’s thesis is a decade old but provides a summary of the research in the area and this survey provides a more recent review).

Compared to the well-studied multimodal route planning problem, the DREAMR setting has two major differences, which primarily contribute to its difficulty. First, the transit networks of DREAMR have much more variability. Public transit has a specific timetable with well-defined stops. In our case, the ‘stops’ depend upon the current vehicles, and the route network changes from one problem instance to another (think of an Uber or Lyft server of currently active cars and their routes). Second, we need real-time control, not one-time solutions. The uncertainty in the drone control and the car route traversal may have downstream effects on making timed connections, and we have to account for this during planning. We concretely capture these challenges by formulating DREAMR as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which is a mathematical framework for modeling sequential decision-making under uncertainty.

Fig. 2: Every DREAMR route is composed of three kinds of sub-routes: Constrained Flight (time-constrained), Riding, and Unconstrained Flight.

Existing off-the-shelf methods for multimodal route planning or Markov Decision Processes cannot be applied naively to solve DREAMR problems. However, two forms of underlying structure will help us cut them down to size — the DREAMR solution routes can be decomposed into simpler sub-routes, as illustrated in figure 2, and there is partial controllability in the system, i.e. drones can be controlled but not cars. We look to exploit this structure intelligently and efficiently in our decision-making framework.

Solving DREAMR with Hierarchical Hybrid Planning

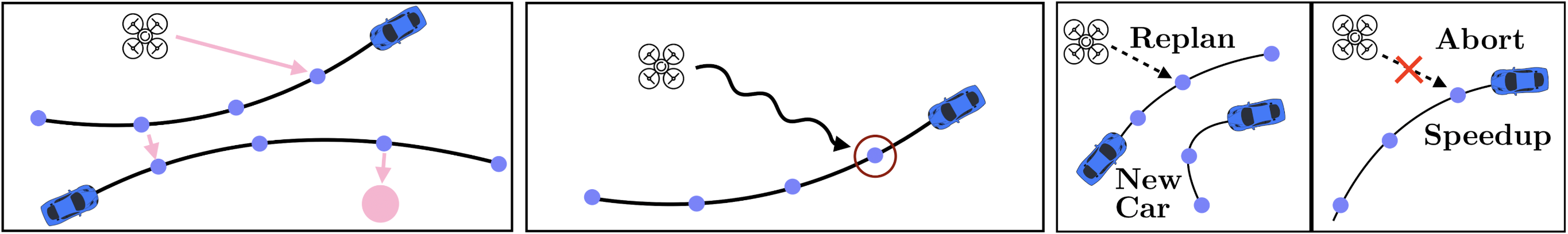

Fig. 3: Our approach exploits the sequential dependency structure for the decisions to be made in DREAMR problems. The choice of transit option defines possible connection points, i.e. where the drone can board a car and alight from it. The chosen connection point determines the appropriate control strategy, i.e. accelerate, decelerate, maintain.

Our planning algorithm relies on analyzing the sequential structure between the decisions that need to be made for DREAMR problems, as illustrated in figure 3. The algorithm is hierarchical, i.e. there is a global layer that repeatedly computes a good nominal route from the drone’s current location to the destination, and a local layer that controls the drone to make the next transit connection for the chosen route. The nature of the decisions is hybrid — the transit choices and connection points are discrete (e.g. choosing a specific metro station) while the control actions are continuous (e.g. velocity or acceleration). Interleaving planning and execution allows adapting to changes such as switching to a new car route that is more helpful, or abandoning a timed connection that is likely to fail when the target car abruptly speeds up.

Fig. 4: The global layer (left) decides which transit options and connection points to aim for; the local layer (middle) controls the agent under uncertainty to make the timed connections; the interleaving (right) responds to better transit options and abrupt speedups/delays.

In our work, we solve large and complex DREAMR problems by introducing carefully chosen representations and abstractions. These choices allow us to combine, in a principled manner, ideas and techniques from diverse decision-making topics. Concepts from heuristic graph search (over routes), planning under uncertainty (to robustly make timed connections), and hierarchical planning (for interleaving) are all necessary to address the various challenges of DREAMR problems and obtain a balance between scalable and good quality solutions. The various technical details are discussed in the paper.

Peeking at some Results

For the experiments, we designed a large-scale simulation setup with hundreds of car routes and thousands of route waypoints on a 10 km x 10 km grid (roughly the size of north San Francisco). The routes are highly variable; new routes can be added after the episode begins and the expected arrival times at current route waypoints are continuously updated. Each time we run the simulation, we give our drones a different start and goal location. For evaluation, we care about two aspects of our approach — scalability to large network sizes and performance of the solution trajectories with respect to the given criteria (energy and time).

Scalability. To evaluate scalability, we examine the search query time for the global route planning layer as the size of the route network, i.e. the number of route waypoints, increases. Even for networks of up to 10000 waypoints and potentially 108 connections, the search query time for a route is 0.6 seconds for the first search (usually the hardest search problem) and 30 - 75 milliseconds for the subsequent updates. These results are competitive with state-of-the-art work on multimodal route planning for humans over public transit networks. Specifically, on public transit networks of 4 x 106 edges (connections), our average query time of 8.19 ms is comparable to theirs of 14.97 ms. The comparison is not exactly apples-to-apples, however, as they have slightly different technical specifications.

Performance. We also examine the tradeoff between energy expended and elapsed time for the solution trajectories obtained by our method, over a wide range of DREAMR scenarios. Our key observation here is that our trajectories have a significantly better tradeoff compared to a deterministic replanning-based method. In particular, the performance gap increases as energy saving is prioritized; more timed connections are attempted , and our approach is much more robust and adaptive in making those timed connections than the baseline. Furthermore, the routes executed by our method save up to 60% energy by judiciously choosing transit options. Some qualitative behavior is demonstrated below (with the longer annotated version here)

The Bottom Line

There are several challenges for multimodal routing in dynamic transit networks, whether it be for delivering packages in cities or mapping unknown terrain. Robots must be able to make complex decisions about where to go and how quickly to get there. Our work is a first step towards framing, understanding, and solving such decision-making problems.

For hierarchical approaches to large and difficult decision-making problems, a smart decomposition into subproblems and recombination of sub-solutions is crucial. The choices of representation and abstraction we use efficiently unite various planning techniques while retaining the generality of the Markov Decision Process formulation and being able to accommodate various different algorithms for each module.

The intelligent abstractions we propose enable us to plan over long horizons while still being computationally efficient. In particular, we achieve better agent behavior by planning under uncertainty. The consideration of uncertainty at the planning stage comes at an increased computational cost because the algorithm has to reason about potentially infinite future scenarios. For complex domains like DREAMR, with space and time constraints for switching between different transit options, explicitly accounting for the downstream effects of uncertainty appears to be worth the extra computational cost.

There are a few interesting directions in which to take this work. We are currently looking at the extension to controlling multiple drones (or autonomous vehicles in general) which brings with it several fascinating challenges in multi-agent planning and scheduling. We’re also examining the underlying Markov Decision Process model for DREAMR and thinking about other robotics decision-making problems that it can represent. And of course, one day soon this technology might come to a delivery drone near you.

N.B. A performant implementation is crucial for real-time decision-making applications,. We used the Julia programming language for fast numerical computations; in particular, we relied heavily on the POMDPs.jl library for modeling and solving Markov Decision Processes.

Our work is presented in the IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium 2019 paper:

Dynamic Real-time Multimodal Routing with Hierarchical Hybrid Planning.

Shushman Choudhury, Jacob P. Knickerbocker, and Mykel J. Kochenderfer

Paper Code

Shushman Choudhury is supported by the Ford Motor Company.