TLDR: How do we finely control the fairness of machine learning systems? In our AISTATS 2019 paper, we introduce a theoretically grounded method for learning controllable fair representations. Using our method, a party who is concerned with fairness (like a data collector, community organizer, or regulatory body) can convert data to representations with controllable limits on unfairness, then release only the representations. This controls how much downstream machine learning models can discriminate.

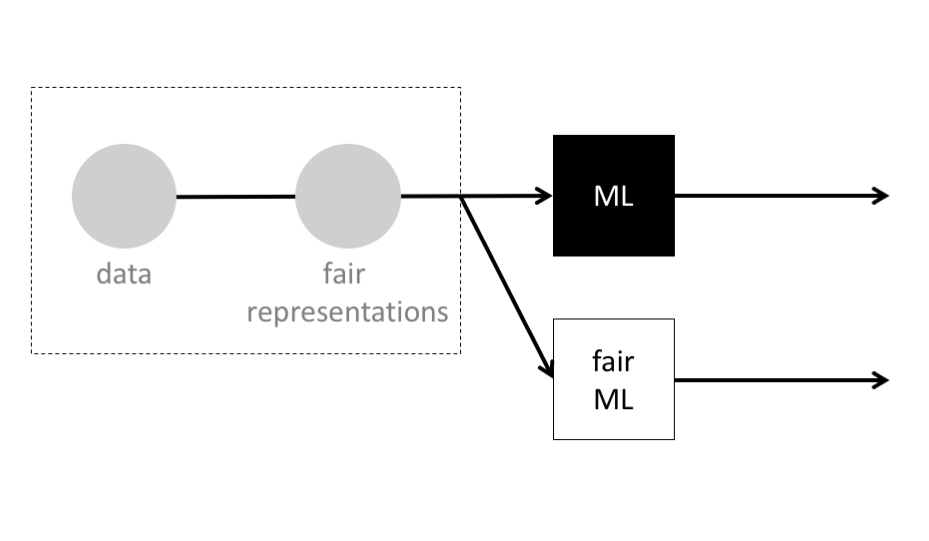

Machine learning systems are increasingly used during high-stakes decisions, influencing credit scores, criminal sentences, and more. This raises an urgent question: how do we ensure these systems do not discriminate based on race, gender, disability, or other minority status? Many researchers have responded by introducing fair machine learning models that balance accuracy and fairness; but this leaves it up to institutions — corporations, governments, etc. — to choose to use these fair models, when some of these instutitions may be agnostic or even adversarial to fairness.

Interestingly, some researchers have introduced methods for learning fair representations 1. Using such methods, a party who is concerned with fairness (like a data collector, community organizer, or regulatory body) can convert data to fair representations, then release only the representations, making it much more difficult for any downstream machine learning models to discriminate.

In this post, we introduce a theoretically grounded approach to learning fair representations, and we discover that a range of existing methods are special cases of our approach. Additionally, we note that all existing methods for learning fair representations can be said to balance usefulness and fairness, producing somewhat-useful-and-somewhat-fair representations. The concerned party must then run the learning process many times until they find representations they find satisfying. Based on our theoretical approach, we introduce a new method where the concerned party can control the fairness of representations by requesting specific limits on unfairness. Compared to earlier fair representations, ours can be learned more quickly, are able to satisfy requests for many notions of fairness simultaneously, and contain more useful information.

A theoretical approach to fair representations

We assume we are given a set of data points (\(x\)), typically representing people, and their sensitive attributes (\(u\)), typically their race, gender, or other minority status. We must learn a model (\(q_\phi\)) mapping any data point to a new representation (\(z\)). Our goal is two-fold: our representations should be expressive — containing plenty of useful information about the data point; and our representations should be fair — containing limited information about the sensititve attributes, so it is difficult to discriminate downstream 2. Note that merely removing sensitive attributes (e.g. race) from the data would not satisfy this notion of fairness, as downstream machine learning models could then discriminate based on correlated features (e.g. zipcode) — a practice called “redlining”.

First, we translate our goal into the information theoretical concept of mutual information. The mutual information between two variables is formally defined as the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the joint probability of the variables and the product of the marginal probabilities of the variables: \(I(u;v) = D_{KL}(P_{(u,v)}\mid\mid P_u \otimes P_v)\); intuitively, it’s the amount of information that is shared. Our goals can be made concrete as follows:

- To achieve expressiveness, we want to maximize the mutual information between the data point \(x\) and the representation \(z\) conditioned on the sensitive attributes \(u\): \(\max I(x;z \mid u)\). (By conditioning on the sensitive attributes, we make sure we do not encourage information in the data point that is correlated with the sensitive attributes to appear in our representation.)

- To achieve fairness, we want to limit the mutual information between the representation \(z\) and the sensitive attributes \(u\): \(I(z;u)<\epsilon\), where \(\epsilon\) has been set by the concerned party.

Next, because both mutual information terms are difficult to optimize, we need to find approximations:

- Instead of maximizing \(I(x;z \mid u)\), we maximize a lower bound \(-L_r \leq I(x;z \mid u)\), which relies on us introducing a new model \(p_\theta(x \mid z,u)\). Intuitively, maximizing \(-L_r\) encourages a mapping such that the new model \(p_\theta\) that takes the representation \(z\) plus the sensitive attributes \(u\) can successfully reconstruct the data point \(x\).

- Instead of constraining \(I(z;u)\), we can constrain an upper bound \(C_1 \geq I(z;u)\). Intuitively, constraining \(C_1\) discourages complex representations.

Or, we can alternatively constrain \(C_2\), a tighter approximation of \(I(z;u)\), which relies on us introducing a new model \(p_\psi(u \mid z)\). Intuitively, constraining \(C_2\) discourages a mapping where the new model \(p_\psi\) that takes the representation \(z\) is able to reconstruct the sensitive attributes \(u\).

Putting it all together, our final objective is to find the models \(q_\phi\), \(p_\theta\), and \(p_\psi\) that encourage the successful reconstruction of the data points, while constraining the complexity of the representations, and constraining the reconstruction of the sensitive attributes:

| Our “hard-constrained” objective for learning fair representations |

|---|

| \(\min_{\theta,\phi}\max_{\psi}\) \(L_r\) \(\text{s.t. }\) \(C_1< \epsilon_1\), \(C_2< \epsilon_2\) |

where \(\epsilon_1\) and \(\epsilon_2\) are limits that have been set by the concerned party.

This gives us a principled approach to learning fair representations. And we are rewarded with a neat discovery: it turns out that a range of existing methods for learning fair representations optimize the dual — a “soft-regularized” version — of our objective!

| The “soft-regularized” loss function for learning fair representations |

|---|

| \(\min_{\theta,\phi}\max_{\psi}\) \(L_r\)\(+\)\(\lambda_1 C_1\)\(+\)\(\lambda_2 C_2\) |

| Existing methods | The \(\lambda_1\) they use | The \(\lambda_2\) they use |

|---|---|---|

| Zemel et al. 20133 | \(0\) | \(A_z/A_x\) |

| Edwards and Storkey 20154 | \(0\) | \(\alpha/\beta\) |

| Madras et al. 20185 | \(0\) | \(\gamma/\beta\) |

| Louizos et al. 20156 | \(1\) | \(\beta\) |

We see that our framework generalizes a range of existing methods!

Learning controllable fair representations

Let’s now take a closer look at the “soft-regularized” loss function. It should feel intuitive that existing methods for learning fair representations produce somewhat-useful-and-somewhat-fair representations, with the balance between expressiveness and fairness controlled by the choice of \(\lambda\)s. If only we could optimize our “hard-constrained” objective instead; then the concerned party could instead set \(\epsilon\) to request specific limits on unfairness . . .

Luckily, there’s a way! We introduce:

| Our loss function for learning controllable fair representations |

|---|

| \(\max_{\lambda \geq 0}\min_{\theta,\phi}\max_{\psi}\)\(L_r\)\(+\)\(\lambda_1 (C_1-\epsilon_1)\)\(+\)\(\lambda_2 (C_2-\epsilon_2)\) |

Intuitively, this loss function dictates that whenever we should be concerned about unfairness because \(C_1 > \epsilon_1\) or \(C_2 > \epsilon_2\), the \(\lambda\)s will place additional emphasis on the unsatisfied constraint; this additional emphasis will persist until \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) return to satisfying the limits \(\epsilon\) set by the concerned party. The rest of the time, when \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) are safely within the limits, minimizing \(L_r\) will be prioritized, encouraging expressive representations.

Results

With this last piece of the puzzle in place, all that’s left to do is evaluate whether our theory leads to learning controllable fair representations in practice. To evaluate, we learn representations of three real-world datasets:

- the UCI German credit dataset of 1,000 individuals, where the binary sensitive attribute

age<50/age>50was to be protected - the UCI Adult dataset of 40,000 adults from the US Census, where the binary sensitive attribute

Man/Womanwas to be protected7 - and the Heritage Health dataset of 60,000 patients, where the sensitive attribute to be protected was the intersection of age and gender: the age-group (of 9 possible age-groups) \(\times\) the gender (

Man/Woman)8

Sure enough, our results confirm that, in all three sets of learned representations, the concerned party’s choices for \(\epsilon_1\) and \(\epsilon_2\) control the approximations of unfairness \(C_1\)and \(C_2\).

Our results also demonstrate that, compared to existing methods, our method can produce more expressive representations.

And our method is able to take care of many notions of fairness simultaneously.

| \(I(x;z \mid u)\) | \(C_1\) | \(C_2\) | \(I_{EO}\) | \(I_{EOpp}\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (higher is expressive) | (lower is fairer) | (lower is fairer) | (lower is fairer) | (lower is fairer) | |

| constraints | < 10 | < .1 | < .1 | < .1 | |

| our method | 9.94 | 9.95 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| existing methods | 9.34 | 9.39 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

While these last two results may seem surprising, they occur because existing methods require the concerned party to run the learning process many times until they find representations they find roughly satisfying, while our method directly optimizes for the representations that are as expressive as possible while equally satisfying all of the concerned party’s limits on unfairness of the representations.

Takeaways

To complement fair machine learning models that corporations and governments can choose to use, this work takes a step towards putting control of fair machine learning in the hands of a party concerned with fairness, such as a data collector, community organizer, or regulatory body. We contribute a theoretical approach to learning fair representations that make it much more difficult for downstream machine learning models to discriminate, and we contribute a new method that allows the concerned party to control the fairness of the representations by requesting specific limits on unfairness, \(\epsilon\).

When working on fair machine learning, it is particularly important to acknowledge limitations and blind-spots; or we risk building toy solutions, while overshadowing others’ work towards equity. A major limitation of our work is that the concerned party’s \(\epsilon\) limits an appoximation of unfairness, and we hope that future work can go further and map \(\epsilon\) to formal guarantees about the fairness of downstream machine learning. Another potential limitation of this work is that we, like much of the fair machine learning community, center demographic parity, equality of odds, and equality of opportunity notions of fairness. We believe that future work will need to develop deeper connections to social-justice-informed notions of equity if it is to avoid shallow technosolutionism and build more equitable machine learning9.

This post is based on our AISTATS 2019 paper:

Learning Controllable Fair Representations

Jiaming Song*, Pratyusha Kalluri*, Aditya Grover, Shengjia Zhao, Stefano Ermon

-

Madras, David, Elliot Creager, Toniann Pitassi, and Richard Zemel. “Learning Adversarially Fair and Transferable Representations.” In ICML, 2018. ↩

-

For conciseness, we focus on demographic parity, a pretty intuitive and strict notion of fairness, but our approach works with many notions of fairness, as shown in our results. ↩

-

Zemel, Rich, Yu Wu, Kevin Swersky, Toni Pitassi, and Cynthia Dwork. “Learning Fair Representations.” In ICML, 2013. ↩

-

Edwards, Harrison, and Amos Storkey. “Censoring Representations with an Adversary.” In ICLR, 2015. ↩

-

Madras, David, Elliot Creager, Toniann Pitassi, and Richard Zemel. “Learning Adversarially Fair and Transferable Representations.” In ICML, 2018. ↩

-

Louizos, Christos, Kevin Swersky, Yujia Li, Max Welling, and Richard Zemel. “The Variational Fair Autoencoder.” In ICLR, 2016. ↩

-

Gender is not binary, and the treatment of gender as binary when using these datasets is problematic and a limitation of this work. ↩

-

Gender is not binary, and the treatment of gender as binary when using these datasets is problematic and a limitation of this work. ↩

-

For more on this, we strongly recommend reading “A People’s Guide to AI” by Mimi Onuoha and Mother Cyborg. Allied Media Projects. 2018. ↩