So much of our lives centers around coordinating in groups. For instance, we are able to coordinate with and influence groups of people both implicitly (e.g. when sharing lanes on the highway) and explicitly (e.g. when cooking a meal together). As robots become increasingly integrated into society, they should be able to similarly coordinate well with human groups.

Examples of group coordination include collaborative cooking, protesting, and navigating crowded spaces.

However, influencing groups of people is challenging. For example, imagine a volunteer search and rescue mission where a drone learns new information about the location of a target (depicted as the blue checkmark below). Assuming that there is no direct mode of communication available, how should the drone lead a team of volunteers toward that location?

The blue arrow represents the desired path and the red arrow represents the current sub-optimal path of the human volunteers.

One way a drone could lead the team would be to model and influence each individual separately. By modeling, we mean understanding and predicting a person’s behavior. However, modeling and influencing people independently of one another does not scale well with larger numbers of individuals and is something that we cannot compute quickly online.

A drone modeling each volunteer individually. This approach doesn't scale well with larger numbers of agents.

Another way to influence a team of humans would be to forgo any modeling and directly learn a policy, or an action plan, from observations of the team. This method provides a plausible solution for teams of a constant size. However, adding or subtracting a team member can change the model’s input size and will require you to re-train your model.

Thus our goal is to develop a framework that enables robots to model and influence human groups and is scalable with the number of human agents.

Our contributions are as follows:

- We introduce a way we can model group interactions in a scalable way.

- We describe how a robot can use this knowledge to influence human teams.

Latent structures in human groups

Instead of modeling each individual in a group, our key idea is to focus on modeling relations among individuals. When we interact in groups, we no longer act in isolation but instead act conditionally based on others’ actions. These dependencies provide structure which we can then use to form expectations of others and behave accordingly. On a larger scale, this allows us to develop norms, conventions, and even cultures. These dependencies are useful for robots because they provide a rich source of information that can help robots model and predict human behavior. We call these dependencies latent structures.

Different driving cultures that have been developed in Japan (left) and India (right).

An important example of latent structures is leading and following behavior. We can easily form teams and decide if we should follow or lead to efficiently complete a task as a group. For instance, in a search and rescue mission, humans can spontaneously become leaders once they discover new information about a target. We also implicitly coordinate leading and following strategies. For example, drivers follow each other across lanes when driving through traffic. We focus on modeling latent leading and following structures as a running example in our work.

Examples of latent leading and following structures among volunteers in a search and rescue mission (left), and cars following each other through traffic (right).

So how do we actually go about modeling these latent structures? And what properties should our ideal model have? Before we get into how we can model latent structures, let’s establish some desiderata:

- Complexity: Since these structures are often implicitly formed, our model should be complex enough to capture complicated relationships among individuals.

- Scalability: We should be able to use our model with changing numbers of agents.

Modeling latent structures

The simplest case

We use a supervised learning approach to estimate relationships between two human agents. Going back to our desiderata, this addresses the issue of complexity because using a learning-based approach allows us to capture complex relationships the pair might have. Using a simulator, we can ask participants to demonstrate the desired relationship we want to measure, such as leading and following.

We abstract the search and rescue mission into a game where goals represent potential survivor locations. In the example below, participants were asked to lead and follow each other in order to collectively decide on a goal to arrive at. Human data is often noisy and difficult to collect in bulk. To make up for these factors, we augmented our dataset with simulated human data. We can then feed this data into neural network modules that are trained to predict leading and following relationships. This gives us a model that can score how likely each agent and goal is to be an agent’s leader.

The network predicts that player 2's leader is player 1.

Scaling up

Now, how can we model a much larger team? Using our model from above, we can represent relationships among multiple humans as a graph by computing scores for pairwise relationships between all agents and goals. Each edge depicted has a probability assigned to it by our trained neural network (probabilities are abstracted away in the graphic below).

We compute pairwise weights of leader-follower relationships between all possible pairs of leaders and followers.

We can then solve for a maximum likelihood graph by pruning the original graph using graph-theoretic algorithms. For instance, we can greedily select the outgoing edge with the highest weight for each agent.

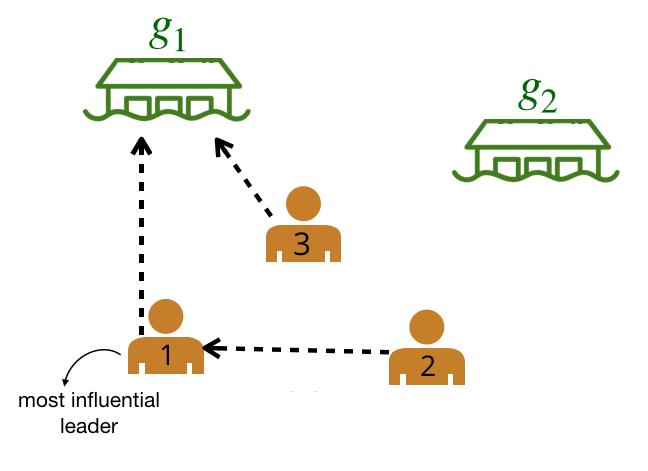

We are left with a graph where the bold edges represent the most likely edges. We call this graph the leader-follower graph (LFG).

Leader-follower graph (LFG). We can use the LFG to identify the most influential leader, the agent with the greatest number of followers.

The graph structure is scalable with the number of agents since we can easily model changing numbers of agents in real-time. For instance, adding an agent in the next $kth$ timestep takes linear time with respect to the number of agents $n$ and the number of goals $m$. In practice, this takes on the order of milliseconds to compute.

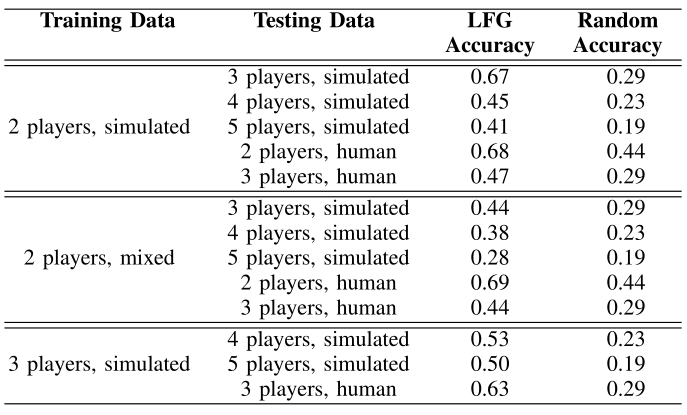

How accurately does our model generalize?

We evaluated how accurately our model generalizes by comparing the predictions made by our leader-follower graph against ground truth predictions. We experimented with training with simulated data and data that contains both simulated and real human data (mixed data). We find that training with larger numbers of players helps with generalization. This suggests that there is a tradeoff between training with smaller numbers of humans and larger numbers (which requires you to collect more data).

How are latent structures useful for robots?

Robots can use latent structures to infer useful information about a team. For instance, in the leading and following example, we can identify information such as agents’ goals or who the most influential leader is. These pieces of information allow the robot to identify key goals or agents that are critical to the task. With this in mind, the robot can then take actions to achieve a desired outcome. Here are two tasks where the robot uses the graph structure to influence human teams:

A. Collaborative task

Being able to lead a team of humans to a goal is useful in many real-life scenarios. For instance, in search-and-rescue missions, robots with more information about the location of survivors should be able to lead the team. We’ve created a similar scenario where there are two goals, or potential locations of survivors, and a robot that knows which location the survivors are at. The robot tries to maximize joint utility by leading all of its teammates to reach the target location. To influence the team, the robot uses the leader-follower graph to infer who the current most influential leader is. The robot then selects actions that maximize the probability of the most influential leader reaching the optimal goal.

In the graphics below, the green circles represent locations (or goals), orange circles are simulated human agents and black circle is the robot. The robot is trying to lead the team towards the more optimal bottom location. We contrast a robot using our graph structure (left) with a robot that greedily targets the optimal goal (right).

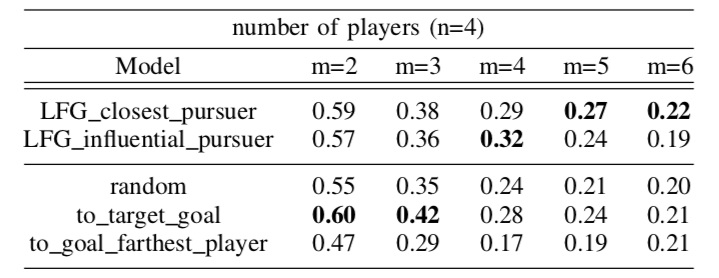

The robot succeeds if the majority of humans collide with the bottom goal first, and fails if the majority collide with the sub-optimal goal. Here is a chart documenting the success rate of a robot using the graph representation compared to a robot using other baseline policies.

Success rate over 100 collaborative games with n=4 players and varying number of goals

We find that our graphical representation is helpful in more difficult scenarios with larger numbers of potential goals.

B. Adversarial task

A robot might also want to prevent a team of humans from reaching a collective goal. For instance, imagine a capture-the-flag game where a robot teammate is trying to prevent the opposing team from capturing any flags.

We’ve created a similar task where a robot wants to prevent a team of humans from reaching a goal. In order to stall the team, the adversarial robot uses the leader-follower graph to identify who the current most influential leader is. The robot then selects actions that maximize the probability of the robot leading the inferred most influential leader away from the goals. An example of the robot’s actions are shown below on the left. On the right, we show an example of a simple policy where a robot randomly chooses one player and unsuccessfully tries to block it.

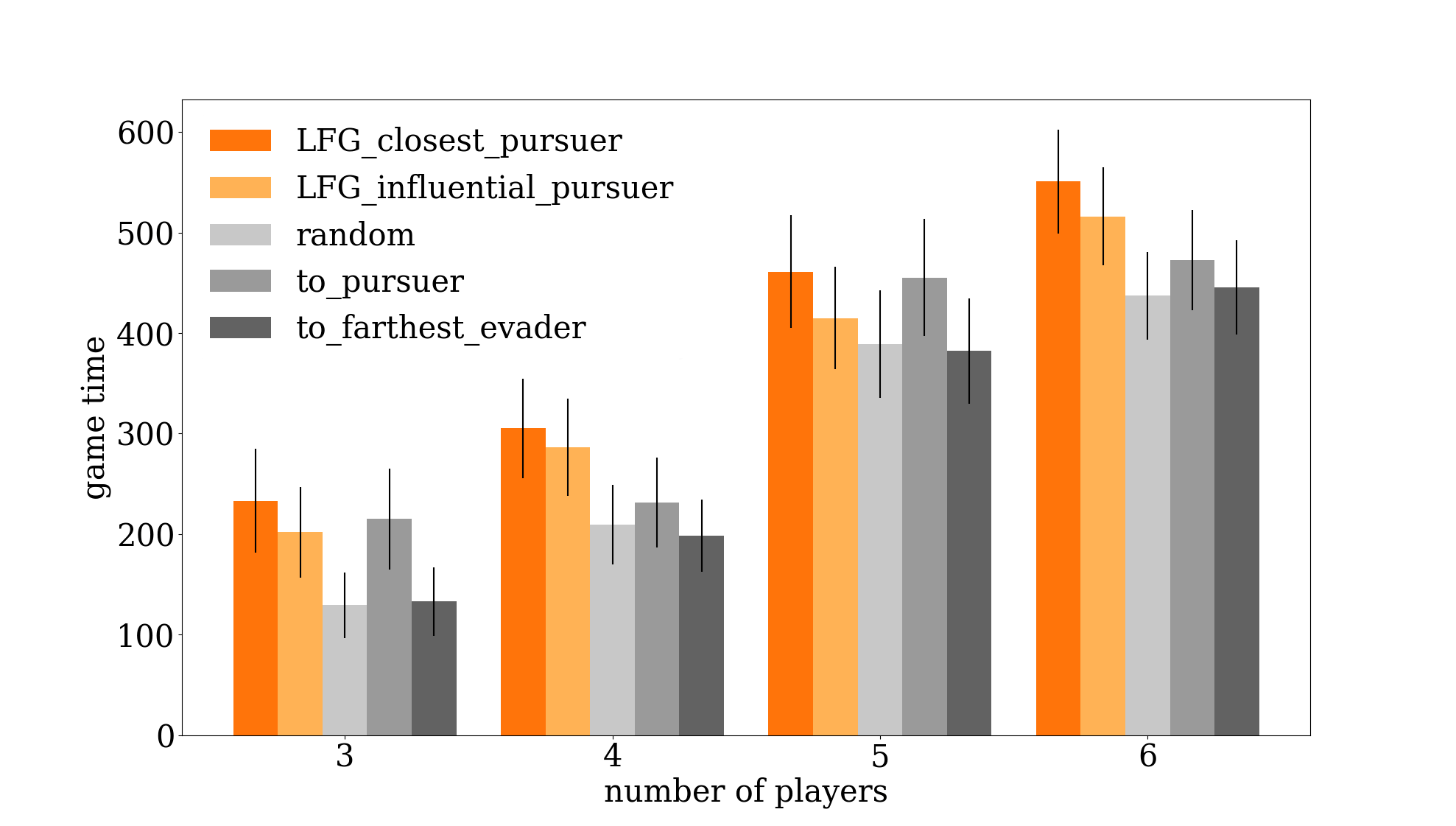

By preventing players from reaching a goal, the robot is trying to extend game time as much as possible. Here is a graph of a robot using our graph representation compared to other baseline policies.

Two policies using the leader-follower graph (LFG) successfully extend game time better than other baseline approaches.

We find that a robot using our graphical representation is the most successful at extending game time compared to other baseline policies.

What’s next?

We’ve introduced a scalable way we can represent inherent structures in human teams. We then demonstrated how we can use this structure to design intelligent influencing behaviors. For future work, we’re interested in a couple of things:

- Real-world experiments. We’re implementing our algorithms on miniature swarm robots so we can conduct human-robot teaming experiments with real robots and humans.

- Varying domains and structures. It would be nice to test our framework on more types of latent structures (e.g., how teammates trust one another) and in different domains (e.g., driving, partially observable settings).

To learn more, please check out the following paper this post was based on:

Influencing Leading and Following in Human-Robot Teams (pdf) Minae Kwon*, Mengxi Li*, Alexandre Bucquet, Dorsa Sadigh Proceedings of Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), June 2019

* denotes equal contribution, and the order of the authors was chosen randomly