The Need for a Benchmark

For a child, learning to communicate is one of life’s biggest adventures. But for millions of kids, this journey has extra hurdles. In the United States alone, over 3.4 million children have speech disorders that need professional help. The problem? There just aren’t enough experts to go around. For every 20 children who need help, there’s only one speech-language pathologist (SLP). This staggering gap means many children wait too long for a diagnosis and miss out on crucial early intervention.

Could multi-modal LLMs like GPT-4 and Gemini help close this gap? Imagine an AI tool that could help an SLP figure out if a child has an articulation disorder (a physical struggle to make a sound, like a lisp) or a phonological disorder (a pattern of errors, like always dropping the last sound of a word, saying “ca” instead of “cat”). The potential is huge, but so are the risks. Using these models without understanding their capabilities and limits could lead to wrong diagnoses and real harm.

The two biggest roadblocks have been a lack of good, clean datasets of children’s speech and no standard way to “grade” these AI models on tasks that actually matter to clinicians.

That’s where our work comes in. We set out to build the first-ever comprehensive “driver’s test” for AI in speech-language pathology. We teamed up with clinical experts to design five key diagnostic tasks, created new datasets to test them, and put 15 of today’s top AI models through their paces. We also tinkered with the models to see if we could make them smarter for this specific job. Our evaluation revealed that there’s no silver bullet; no single model consistently outperformed the others nor did they meet clinical standards. We also uncovered systematic disparities; with models performing better on male children, and found that popular prompting techniques like asking the model to “think step-by-step” can actually hurt performance on nuanced diagnostic tasks. But there’s good news: by fine-tuning the models on domain-specific data, we achieved improvements of over 10%. We’re making all of our datasets, models, and our testing framework public to help everyone build safer and more helpful AI for SLPs and the kids they support

SLPHelm: An SLP ‘Drivers Test’

Note: This section contains details on our evaluation framework; you can skip it if you want to focus on the evaluation results.

To build an AI tool that an SLP would actually find useful, you have to test it on real-world problems. We quickly realized that existing research datasets were a major bottleneck. Most of them could only do one thing: label a speech sample as either “disordered” or “typical”. That’s like a doctor only being able to tell you if you’re “sick” or “healthy”—it’s not nearly specific enough to be helpful. “Disordered” could mean anything from a lisp to a pattern of omitting sounds, like saying ‘ca’ for ‘cat’.

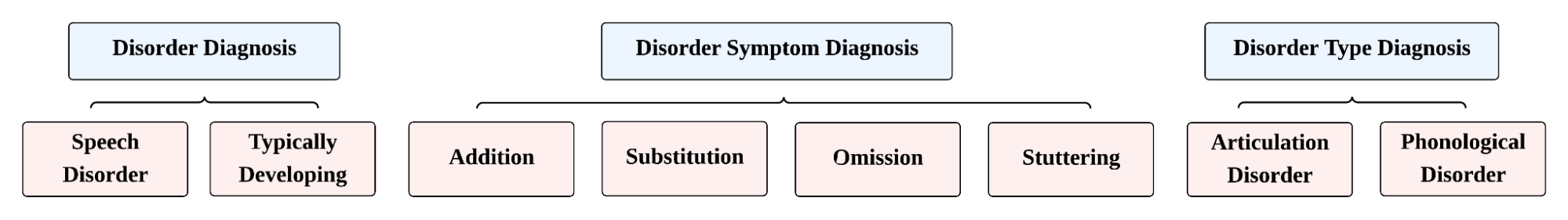

To fix this, we worked side-by-side with a certified SLP to create a much more detailed system for labeling speech. Our new taxonomy (Figure 1) organizes diagnosis into three levels:

- At the highest level, it makes the primary distinction between speech that is Typically Developing and speech that exhibits a Speech Disorder. A pediatric speech disorder is a clinical deviation from expected speech development patterns that requires intervention. This initial classification is the most critical early triage step for prioritizing clinical resources.

-

For speech identified as disordered, the taxonomy allows for two different, more granular levels of classification:

- By Disorder Type: This level distinguishes between an Articulation Disorder, which involves motor-based difficulty in physically producing specific sounds (like a lisp), and a Phonological Disorder, which involves pattern-based errors in understanding and using the sound system of a language (e.g., consistently saying “ca” for “cat”).

- By Disorder Symptom: This level pinpoints the specific clinical symptoms present. These include Substitution (replacing one sound with another), Omission (dropping a sound), Addition (inserting an extra sound), and Stuttering (disruptions in speech fluency).

With this detailed map in place, we created our evaluation framework, SLPHelm. We challenged the AI models with five key tasks:

- Disorder Diagnosis: The foundational task of distinguishing between typical and disordered speech is a critical first step in clinical triage.

- Transcription-Based Diagnosis: A baseline task that checks for mismatches between a model’s transcription and the expected text, providing a simple, interpretation-free diagnostic heuristic.

- Transcription: A measure of automatic speech recognition (ASR) accuracy on disordered child speech, which is essential for many downstream tasks.

- Disorder Type Classification: A more advanced task where models must differentiate between articulation disorders (motor-based errors) and phonological disorders (pattern-based errors).

- Symptom Classification: The most granular task, requiring models to identify specific error types like substitutions (e.g., “gape” for “gate”), omissions (“gore” for “gorge”), additions, or stuttering.

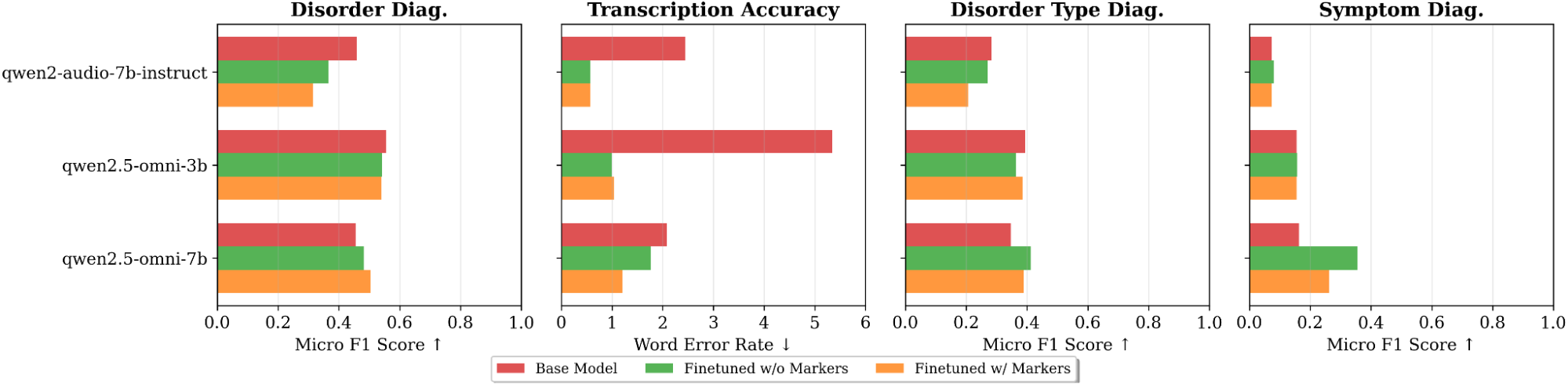

We evaluated 15 closed and open-source models, including families like GPT-4, Gemini, Qwen, and IBM Granite. Additionally, we investigated whether domain-specific fine-tuning could improve performance on SLP scenarios. We explored two primary strategies:

- Standard ASR Fine-tuning: Training a model on a speech recognition task using both typical and disordered speech samples with their correct transcriptions.

- Marked ASR Fine-tuning: To help the model better distinguish between typical and disordered speech, we used a simple but effective trick: we appended an asterisk (*) to each word in the transcription of a disordered speech sample. This gives the model an explicit signal to learn disorder-specific patterns without changing the core task.

The Results: Biases, Blind Spots, and Bright Spots

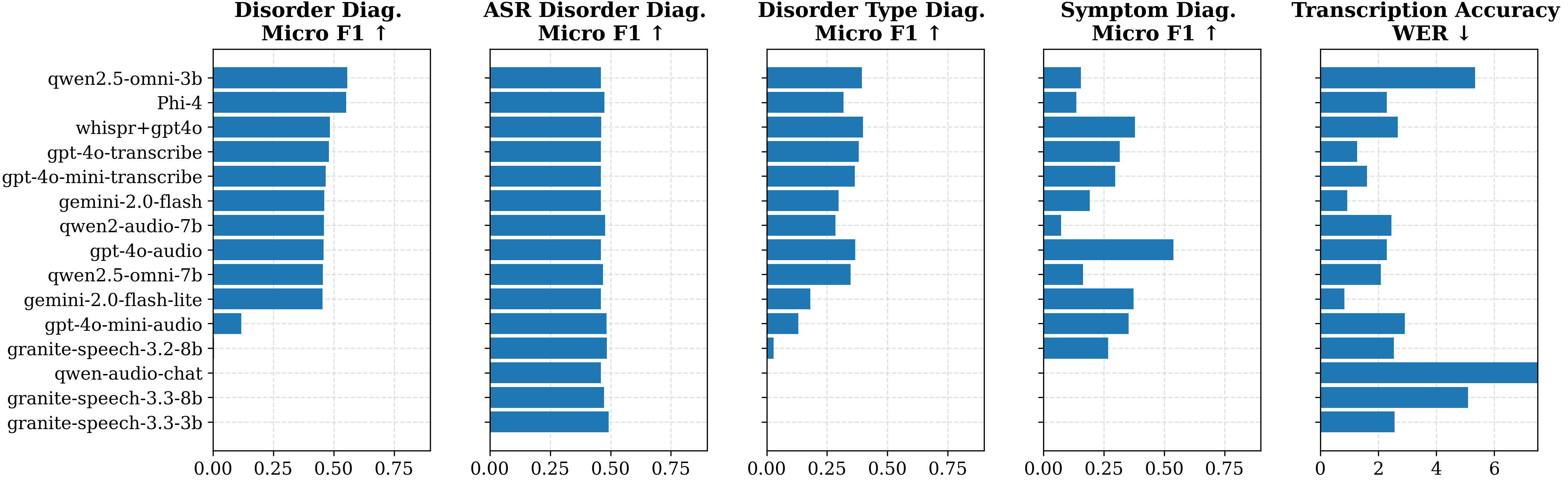

Our comprehensive evaluation reveals that no single model excels across all tasks, and most current models fall short of the reliability needed for clinical use. Existing FDA-approved AI diagnostic systems typically achieve F1 scores between 0.80 and 0.85; none of our evaluated models reached this standard for classification tasks.

Here are the most interesting takeaways:

-

Today’s AI Isn’t Ready for the Clinic. In the most fundamental task—simply telling disordered from typical speech—the best model (Qwen 2.5-Omni-3B) has an F1 score of 0.56, which is below the bar for being clinically useful. This is a significant warning sign that simply deploying a powerful AI off the shelf to tackle a clinical problem is a risky idea.

-

ASR Fine-tuning Can Be Effective: Fine-tuning large models can boost their performance on specific downstream tasks. We observed consistent gains in ASR-based tasks (Scenarios 2 and 3) when fine-tuning solely on ASR data, regardless of whether disordered speech was explicitly marked. However, improvements beyond these scenarios were not uniform across models; Qwen2.5-Omni-7b showed gains in Scenarios 4 and 5, whereas others did not. While the performance advantage from finetuning did not extend to all scenarios across all models, it highlights a promising direction for building more specialized models for SLP.

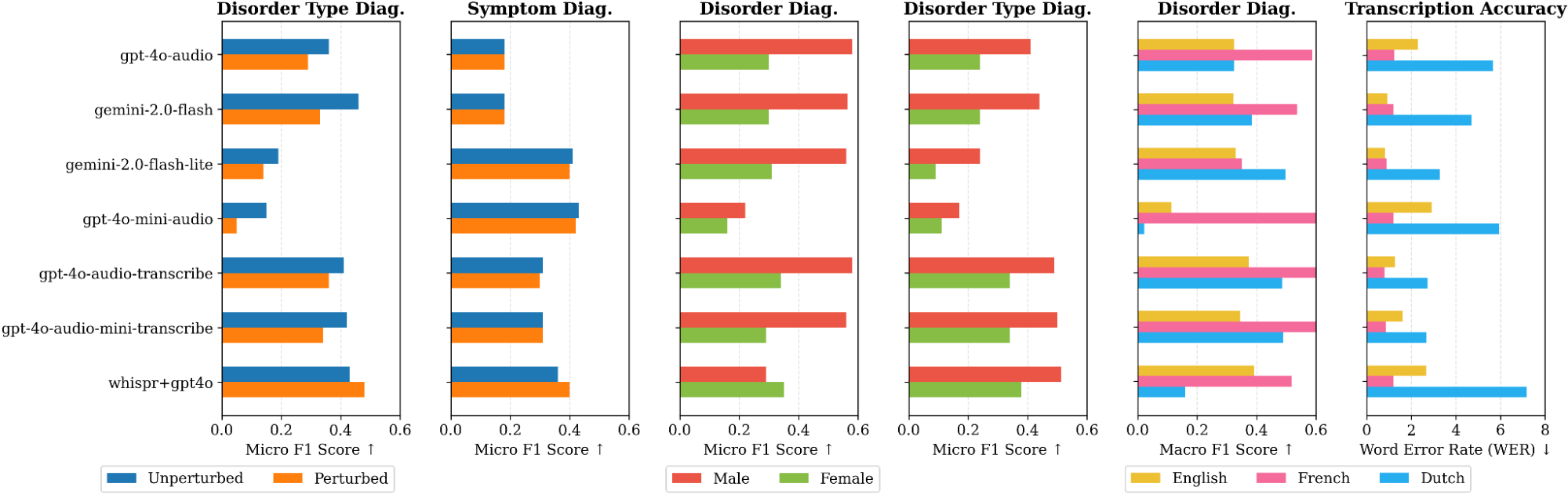

- A Systematic Bias Towards Male Speakers: Our analysis revealed a consistent and concerning performance gap, where nearly every model performed better on speech from male children compared to female children. This disparity appeared in both audio-native and transcription-based models. A potential cause is an imbalance in training data, as persistent speech disorders are more commonly documented in boys. This finding highlights a critical need for gender-balanced auditing and fine-tuning to ensure equitable care.

-

Transcription ≠ Diagnosis: We found that high-quality transcription is neither necessary nor sufficient for accurate diagnosis. Some models with mediocre transcription accuracy were still strong classifiers, likely because they leverage higher-level acoustic cues (like prosody and articulation) that are lost in a pure text transcript. This suggests that end-to-end, audio-native models may hold an advantage for complex diagnostic reasoning.

-

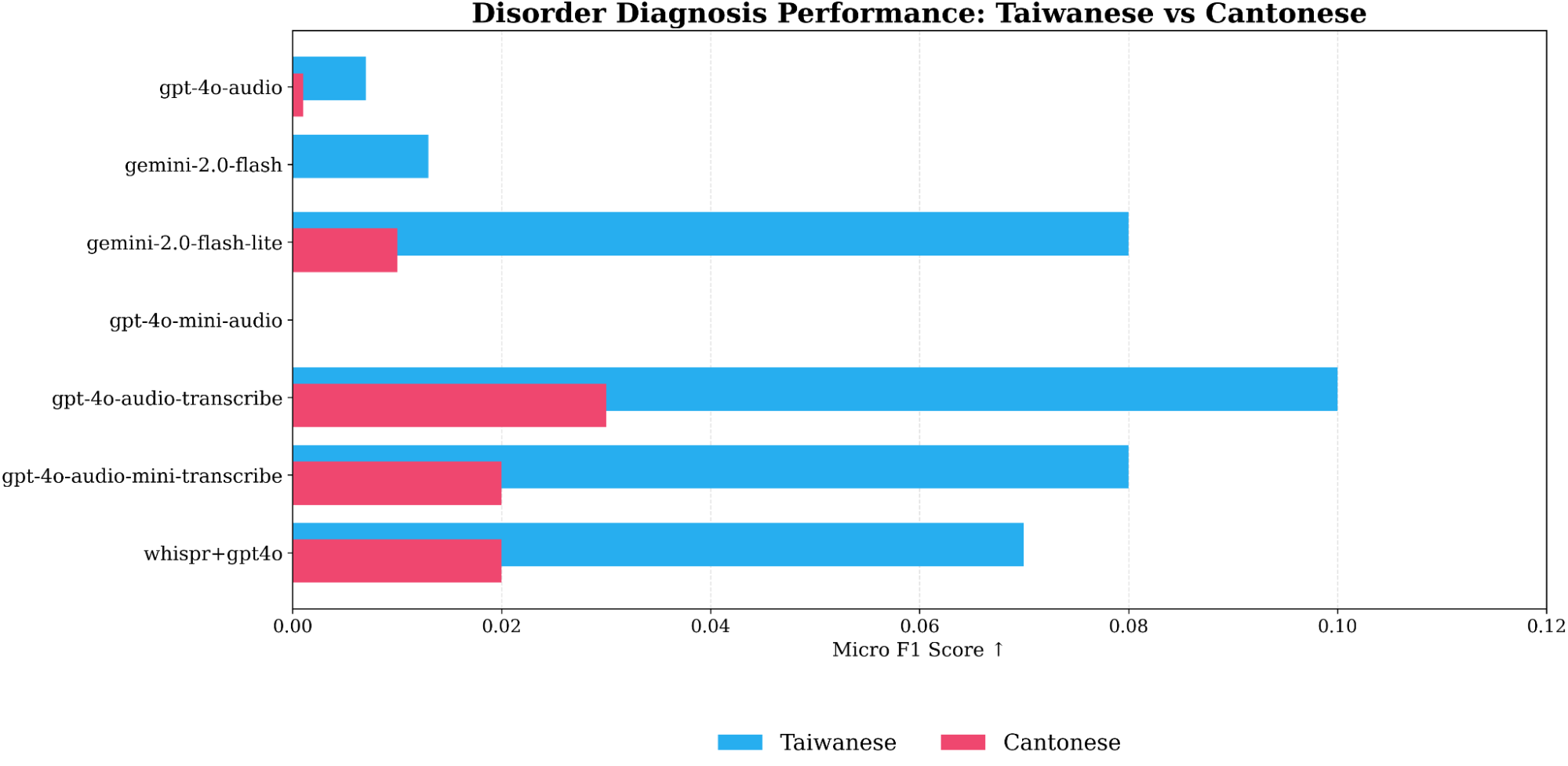

Models Fail on Tonal Languages: In a preliminary analysis, we found that current models completely fail to generalize to tonal languages like Taiwanese and Cantonese. The models systematically misclassified typical speech as disordered, suggesting they confuse the natural tonal variations in these languages with pathological speech patterns. This is a critical limitation for global applications.

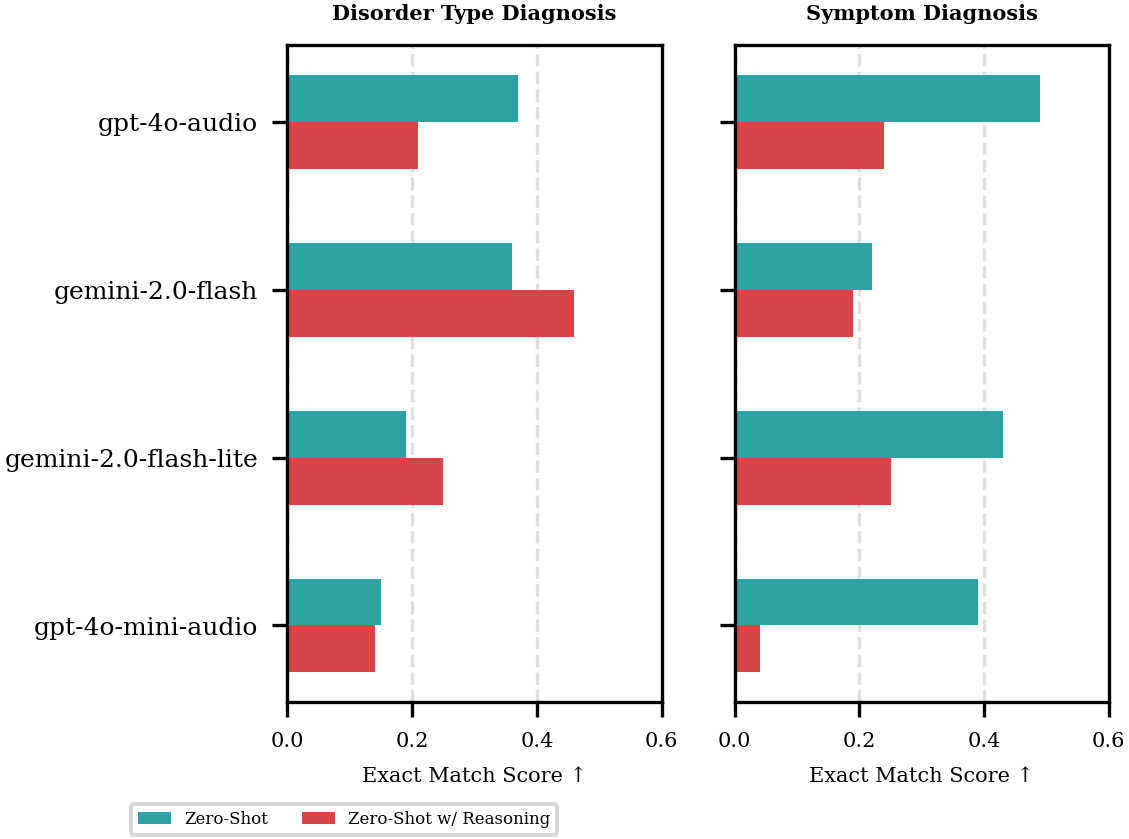

Chain-of-Thought Can Backfire: When ‘Thinking’ Hurts Performance

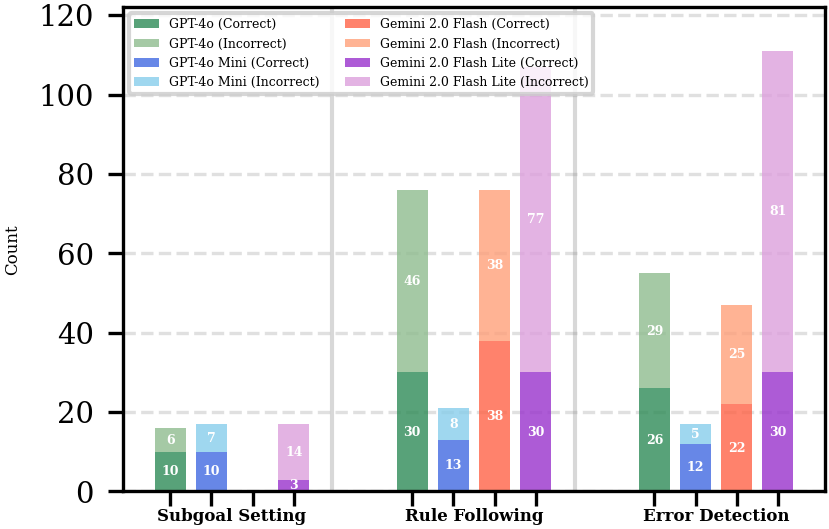

Contrary to the common wisdom that Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting improves reasoning, we found it systematically degraded performance on some of our complex classification tasks. This aligns with recent evidence suggesting CoT can hamper tasks where the decision boundary is narrow or the answer format is strict, as the additional reasoning tokens can introduce “distraction” or bleed into the final predicted label. However, the explicit step-by-step rationale gives crucial insight into why a model failed. To gain a deeper understanding, we analyzed 200 reasoning traces from four different models, focusing on the following behaviours:

- Error Detection: Recognizing individual, raw errors in speech. This is an observation step. For instance, identifying that a child said “tai” for “kai” and “dow” for “cow” involves detecting two specific sound substitutions.

- Rule Following: Applying a broader clinical or taxonomical rule to the detected errors to reach a conclusion. This is an inference step. Using the same example, the model would apply the rule that a consistent pattern of substituting back-of-the-mouth sounds (/k/) for front-of-the-mouth sounds (/t/, /d/) indicates a phonological disorder.

- Subgoal Setting: breaking down a complex problem into manageable steps (e.g., ``To solve this, we first need to…’’).

Our analysis revealed key differences in how effectively the models reasoned. For example, GPT-4o frequently attempted to follow rules and detect errors, but its application of these strategies was often flawed, leading to an incorrect final answer in the majority of cases. This “high rate of flawed application” likely explains its drop in performance with CoT. Conversely, Gemini 2.0 Flash’s performance improved, correlating with more reliable reasoning; its application of “Rule Following” was correct in 50% of instances, compared to just 39.5% for GPT-4o. This suggests that for these specialized SLP tasks, CoT only helps when the model can reliably apply reasoning strategies within a well-defined problem space.

Conclusion: Where Do We Go From Here?

Our work is the first major benchmark for AI in pediatric speech pathology, and our findings are a mix of good news and bad news.

The bad news is that today’s off-the-shelf AI models are not ready or reliable enough to be used in a clinic. We also found that popular AI tricks don’t always work in this specialized medical field, and we uncovered serious biases related to gender and language that must be fixed. But the good news is that we have a path forward. We showed that smart, targeted finetuning—like our marked ASR method—can dramatically improve performance.

This research is a crucial first step. The goal is not to replace clinicians but to develop ethical, reliable, and clinically valuable tools that can augment their capabilities. Future research should prioritize the expansion of this framework to include more low-resource and tonal languages, the development of privacy-preserving fine-tuning methods suitable for sensitive pediatric data, and the creation of AI-generated explanations that are clinically faithful and genuinely useful to SLPs. By pursuing this trajectory, we can work toward bridging the significant gap in care and providing timely support to the millions of children who require it.