A key aspect of human learning is imitation: the capability to mimic and learn behavior from a teacher or an expert. This is an important ability for acquiring new skills, such as walking, biking, or speaking a new language. Although current Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems are capable of complex decision-making, such as mastering Go, playing complex strategic games like Starcraft, or manipulating a Rubik’s cube, these systems often require over 100 million interactions with an environment to train — equivalent of more than 100 years of human experience — to reach human-level performance. In contrast, a human can acquire new skills in relatively short amounts of time by observing an expert. How can we enable our artificial agents to similarly acquire such fast learning ability?

Another challenge with current AI systems is that they require explicit programming or hand-designing of reward functions in-order to make correct decisions. These methodologies are frequently brittle, or otherwise imperfect, and can lead to these systems struggling to work well in complex situations — with self-driving cars blockading roads, or robots failing to coordinate with humans. Developing new methods that can instead interactively learn from human or expert data can be a key stepping stone towards sample-efficient agents and learning human-like behavior.

In this post, I’ll discuss several techniques being developed in a field called “Imitation Learning” (IL) to solve these sorts of problems and present a recent method from our lab, called Inverse Q-Learning — which was used to create the best AI agent for playing Minecraft using few expert demos1. You can check out the project page here, and the code for the underlying method here.

So, what is imitation learning, and what has it been used for?

In imitation learning (IL), an agent is given access to samples of expert behavior (e.g. videos of humans playing online games or cars driving on the road) and it tries to learn a policy that mimics this behavior. This objective is in contrast to reinforcement learning (RL), where the goal is to learn a policy that maximizes a specified reward function. A major advantage of imitation learning is that it does not require careful hand-design of a reward function because it relies solely on expert behavior data, making it easier to scale to real-world tasks where one is able to gather expert behavior (like video games or driving). This approach of enabling the development of AI systems by data-driven learning, rather than specification through code or heuristic rewards, is consistent with the key principles behind Software 2.0.

Imitation learning has been a key component in developing AI methods for decades, with early approaches dating back to the 1990s and early 2000s, including work by work by Andrew Ng and Stuart Russel, and the creation of the first self-driving car systems. Recently, imitation learning has become an important topic with increasing real-world utility, with papers using the technique for driving autonomous cars, enabling robotic locomotion, playing video games, manipulating objects, and even robotic surgery.

Imitation Learning as Supervision

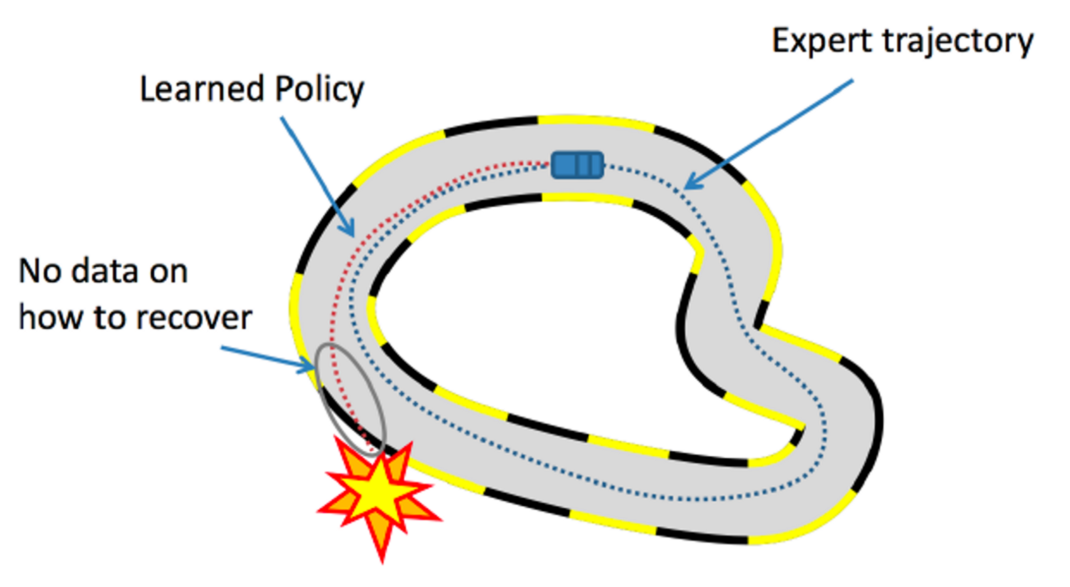

Early approaches to imitation learning seek to learn a policy as a machine learning model that maps environment observations to (optimal) actions taken by the expert using supervised learning. The method is called Behavioral Cloning (BC), but it has a drawback: BC has loose, or no, guarantees that the model will generalize to unseen environmental observations. A key issue is that when the agent ends up in an situation that is unlike any of the expert trajectories, BC is prone to failures. For example, in the figure above, the car agent doesn’t know what to do if it goes away from the expert trajectory and it crashes. To avoid making a mistake, BC requires expert data on all possible trajectories in the environment, making it a heavily data-inefficient approach.

A simple fix, Dataset Aggregation (DAGGER), was proposed to interactively collect more expert data to recover from mistakes and was used to create the first autonomous drone that could navigate forests. Nevertheless, this requires a human in the loop and such interactive access to an expert is usually infeasible. Instead, we want to emulate the trial-and-error process that humans use to fix mistakes. For the above example, if the car agent can interact with the environment to learn “if I do this then I crash,” then it could correct itself to avoid that behavior.

This insight led to the formulation of imitation learning as a problem to learn a reward function from the expert data, such that a policy that optimizes the reward through environment interaction matches the expert, thus inverting the reinforcement learning problem; this approach is termed Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL).

How do recent Imitation Approaches using IRL work?

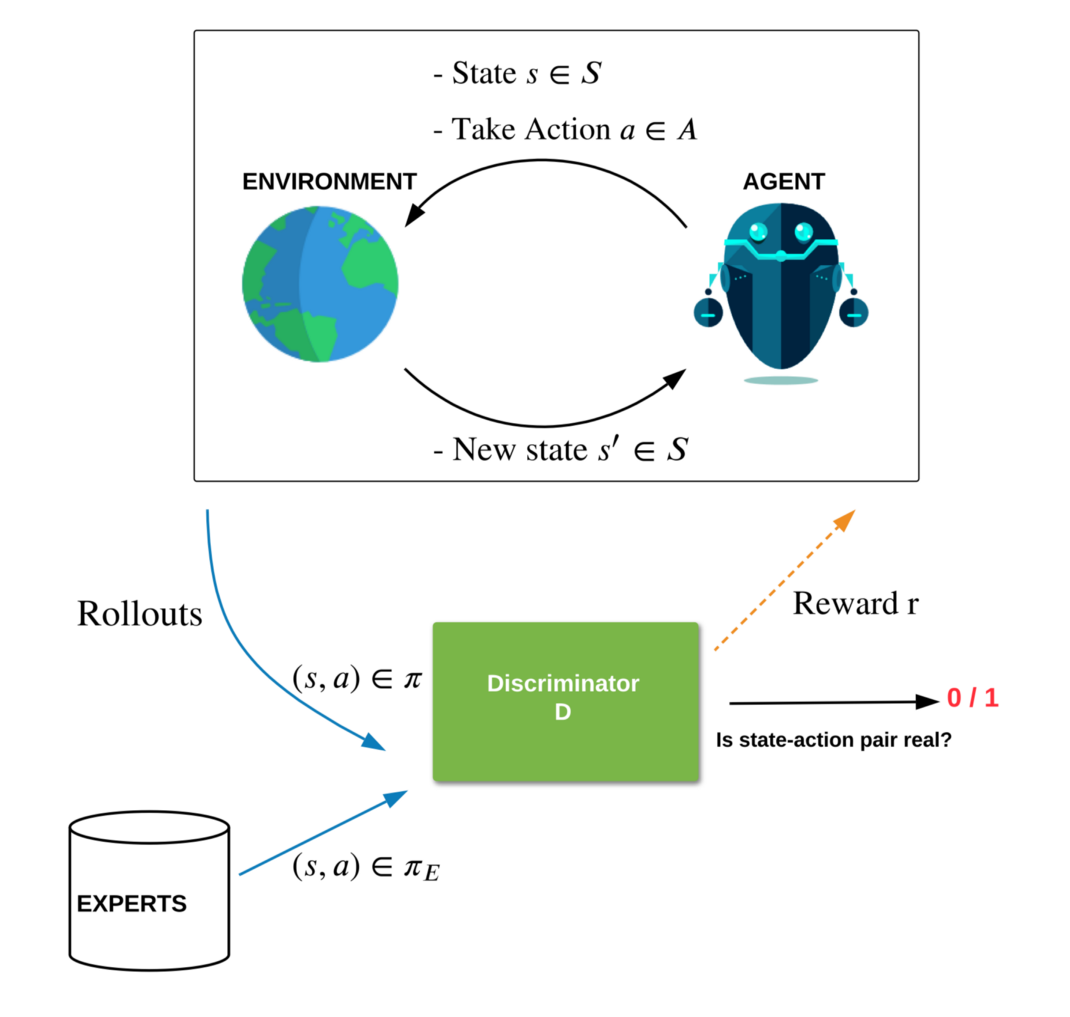

In 2016, Ho and Ermon posed Inverse Reinforcement Learning as a minimax game between two AI models with simple parallels to GANs — a class of generative models. In this formulation, the agent policy model (the “generator”) produces actions interacting with an environment to attain the highest rewards from a reward model using RL, while the reward model (the “discriminator”) attempts to distinguish the agent policy behavior from expert behavior. Similar to GANs, the discriminator acts as a reward model that indicates how expert-like an action is.

Thus, if the policy does something that is not expert-like, it gets a low reward from the discriminator and learns to correct this behavior. This minimax game has a unique equilibrium solution called the saddle point solution (due to the geometrical saddle shape of the optimization). At the equilibrium, the discriminator learns a reward such that the policy behavior based on it is indistinguishable from the expert. With this adversarial learning of a policy and a discriminator, it is possible to reach expert performance using few demonstrations. Techniques inspired by such are referred to as Adversarial Imitation. (see the figure below for an illustration of the method)

Unfortunately, as adversarial imitation is based on GANs, it suffers from the same limitations, such as mode collapse and training instability, and so training requires careful hyperparameter tuning and tricks like gradient penalization. Furthermore, the process of reinforcement learning complicates training because it is not possible to train the generator here through simple gradient descent. This amalgamation of GANs and RL makes for a very brittle combination, which does not work well in complex image-based environments like Atari. Because of these challenges, Behavioral Cloning remains the most prevalent method of imitation.

Learning Q-functions for Imitation

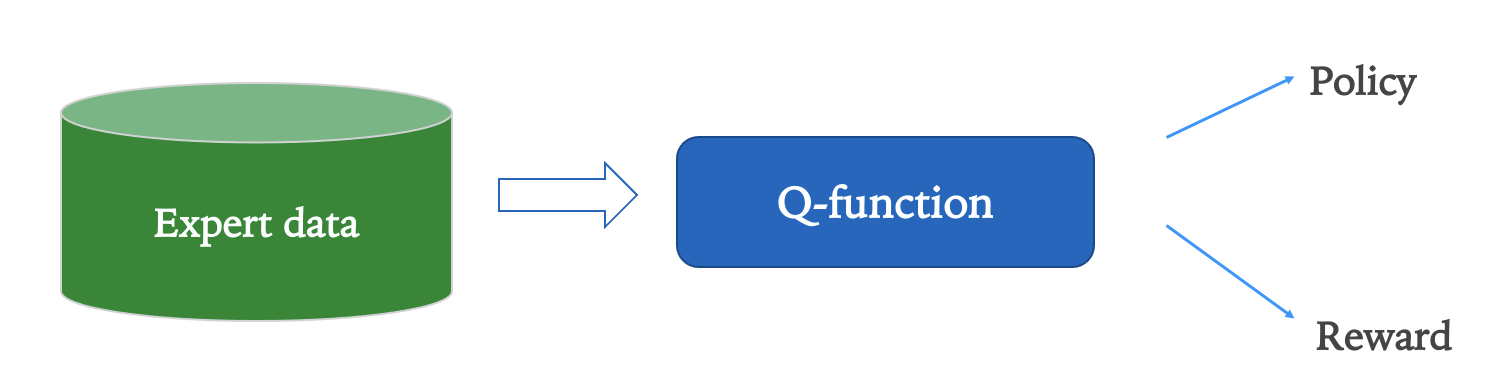

These issues, recently, have led to a new non-adversarial approach for imitation: learning Q-functions to recover expert behavior.

In RL, Q-functions measure the expected sum of future rewards an agent can obtain starting from the current state and choosing a particular action. By learning Q-functions using a neural network that takes in the current state and a potential action of the agent as input, one can predict the overall expected future reward obtained by the agent. Because the prediction is of the overall reward, as opposed to only the reward for taking that one step, determining the optimal policy is as simple as sequentially taking actions with the highest predicted Q-function values in the current state. This optimal policy can be represented as the argmax over all possible actions for a Q-function in a given state. Thus, the Q-function is a very useful quantity, providing a connection between the reward function and the optimal behavior policy in an environment.

In IL, a simple, stable, and data-efficient approach has always been out of reach because of the above-mentioned issues with previous approaches. Additionally, the instability of adversarial methods makes the Inverse RL formulation hard to solve. A non-adversarial approach to IL could likely resolve many of the challenges the field faces. Is there something to learn for IL from the remarkable success of Q-functions in RL to determine the optimal behavior policy from a reward function?

Inverse Q-Learning (IQ-Learn)

To determine reward functions, what if we directly learn a Q-function from expert behavior data? This is exactly the idea behind our recently proposed algorithm, Inverse Q-Learning (IQ-Learn). Our key insight is that not only can the Q-function represent the optimal behavior policy but it can also represent the reward function, as the mapping from single-step rewards to Q-functions is bijective for a given policy2. This can be used to avoid the difficult minimax game over the policy and reward functions seen in the Adversarial Imitation formulation, by expressing both using a single variable: the Q-function. Plugging this change of variables into the original Inverse RL objective leads to a much simpler minimization problem over just the single Q-function; which we refer to as the Inverse Q-learning problem. Our Inverse Q-learning problem shares a one-to-one correspondence with the minimax game of adversarial IL in that each potential Q-function can be mapped to a pair of discriminator and generator networks. This means that we maintain the generality and unique equilibrium properties of IRL while resulting in a simple non-adversarial algorithm that may be used for imitation.

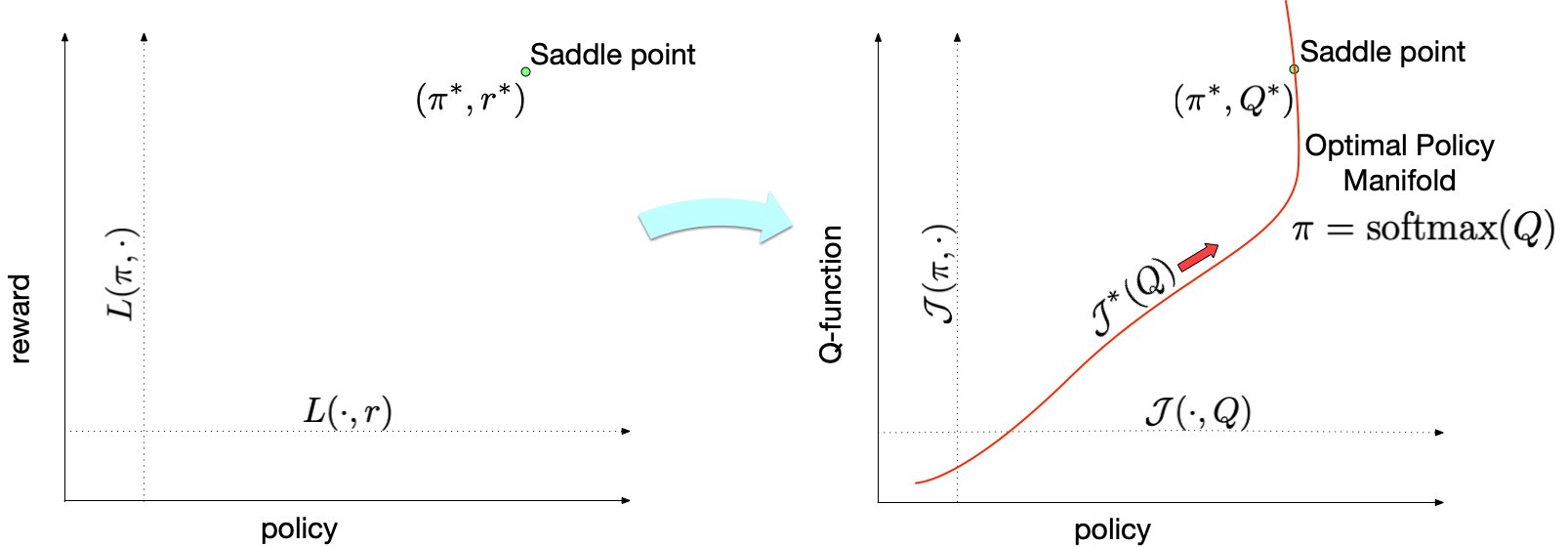

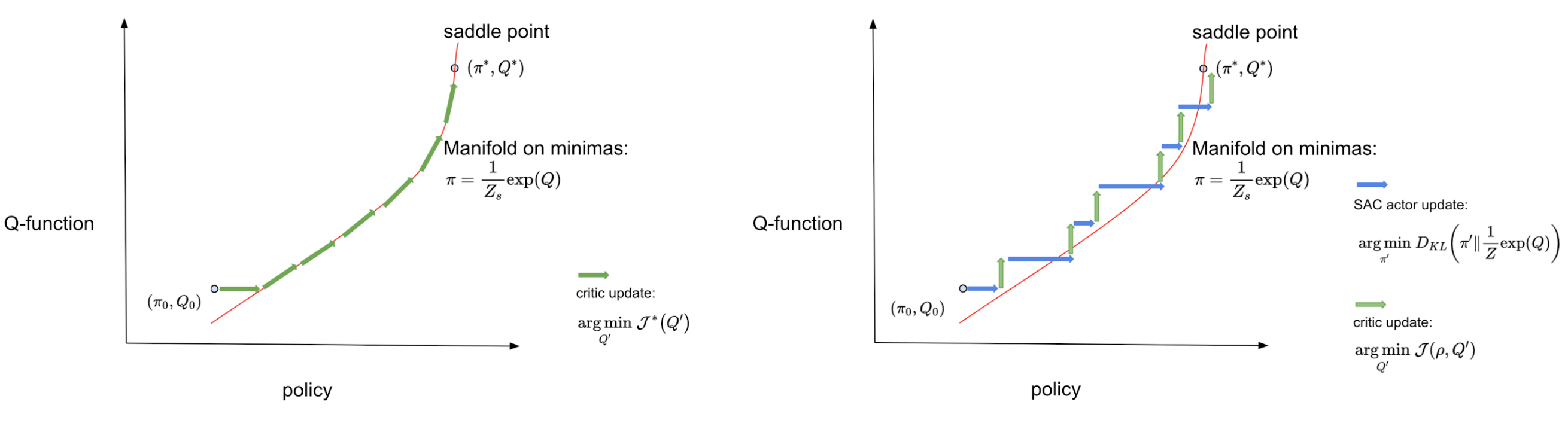

Below is a visualization to intuitively understand our approach – existing IRL methods solve an involved minimax game over policy (\(\pi\)) and rewards (\(r\)), finding a policy that matches expert behavior at the unique saddle point solution (\(\pi^*\), \(r^*\)) by utilizing RL (shown in left). IQ-Learn proposes a simple transformation from rewards to Q-functions to instead solve this problem over the policy (\(\pi\)) and the Q-function (\(Q\)) to find the corresponding solution (\(\pi^*\), \(Q^*\)) (shown in right). Now crucially, if we know the Q-function then we explicitly know the optimal policy for it: this optimal policy is to simply choose the (softmax) action that maximizes the Q-function in the given state 3. Thus, IQ-Learn removes the need for RL to find the policy!

Now, instead of optimizing over the space of all possible rewards and policies, we only need to optimize along a manifold in this space corresponding to the choice of a Q-function and the optimal policy for it (the red line). The new objective along the manifold \(\mathcal{J}^*\) is concave and dependent only on the Q-function variable, allowing the use of simple gradient descent methods to find the unique optima.

During the course of learning, for discrete action spaces, IQ-Learn optimizes the objective \(\mathcal{J}^*\), taking gradient steps on the manifold with respect to the Q-function (the green lines) converging to the globally optimal saddle point. For continuous action spaces calculating the exact gradients is often intractable and IQ-Learn additionally learns a policy network. It updates the Q-function (the green lines) and the policy (the blue lines) separately to remain close to the manifold. You can read the technical proofs and implementation details in our paper.

This approach is quite simple and needs only a modified update rule to train a Q-network using expert demonstrations and, optionally, environment interactions. The IQ-Learn update is a form of contrastive learning, where expert behavior is assigned a large reward, and the policy behavior a low reward; with rewards parametrized using Q-functions. It can be easily implemented in less than 15 lines on top of existing Q-learning algorithms in discrete action spaces, and soft actor-critic (SAC) methods for continuous action spaces.

IQ-Learn has a number of advantages:

- It optimizes a single training objective using gradient descent and learns a single model for the Q-function.

- It is performant with very sparse data — even single expert demonstrations.

- It is simple to implement and can work in both settings: with access to an environment (online IL) or without (offline IL).

- It scales to complex image-based environments and has proven theoretical convergence to a unique global optimum.

- Lastly, it can be used to recover rewards and add interpretability to the policy’s behavior.

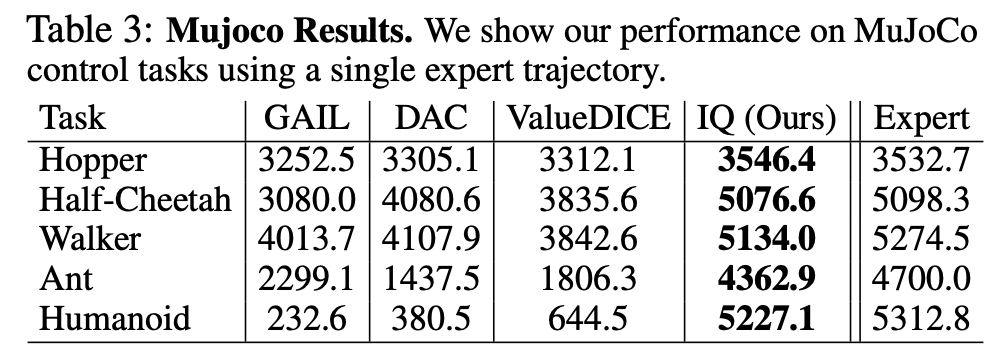

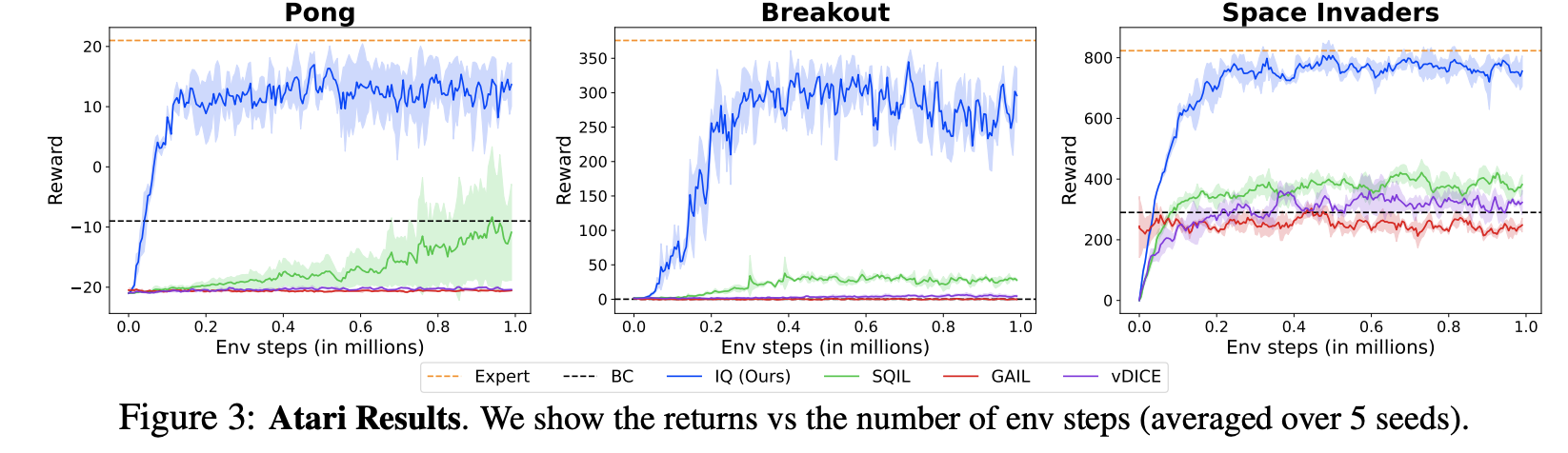

Despite the simplicity of the approach, we were surprised to find that it substantially outperformed a number of existing approaches on popular imitation learning benchmarks such as OpenAI Gym, MujoCo, and Atari, including approaches that were much more complex or domain-specific. In all these benchmarks, IQ-Learn was the only method to successfully reach expert performance by relying on a few expert demonstrations (less than 10). IQ-Learn with a simple LSTM policy also works surprisingly well in the complex open-world setting of Minecraft and is able to learn from videos of human players to solve various tasks like building a house, creating a waterfall, caging animals, and finding caves4.

Beyond simple imitation, we also tried to imitate experts where only partial expert data is available or the expert has changes in its environment or goals compared to the agent — more akin to the real world. We were able to show that IQ-Learn can be used for imitation without expert actions, and relying solely on expert observations, enabling learning from videos. Moreover, IQ-Learn was surprisingly robust to distribution shifts in the expert behavior and goals in an environment, showing great generalization to new unseen settings and an ability to act as a meta-learner.

See videos of IQ-Learn below (trained with Image observations):

Performance Comparisions (from the paper):

The performance is measured as the environment reward attained by the agent trained using different methods.

The performance is measured as the environment reward attained by the agent trained using different methods.

The generality of our method — it can be combined with any existing Q-learning or actor-critic implementations — makes IQ-Learn applicable to a wide range of domains and learning objectives in imitation and reinforcement learning beyond those explored in the paper.

We hope that IQ-Learn’s simple approach to learning policies via imitation of a few experts will bring us one step closer to developing sample-efficient general AI agents that can learn a variety of behavior from humans in real-world settings.

I would like to thank Stefano Ermon, Mo Tiwari and Kuno Kim for valuable suggestions and proofreading. Also thanks to Jacob Schreiber, Megha Srivastava and Sidd Karamcheti for their helpful and extensive comments. Finally, acknowledging Skanda Vaidyanath, Susan R. Qi and Brad Porter for their feedback

This last part of this post was based on the following research paper:

- IQ-Learn: Inverse soft-Q Learning for Imitation. D. Garg, S. Chakraborty, C. Cundy, J. Song, S. Ermon. In NeurIPS, 2021 (Spotlight). (pdf, code)

-

IQ-Learn won the #1 place in NeurIPS ‘21 MineRL challenge to create an AI to play Minecraft trained using imitation on only 20-40 expert demos (< 5 hrs demo data). Recently, OpenAI released VPT which is the current best in playing Minecraft but in comparison utilizes 70,000 hours of demo data. ↩

-

As the Q-function estimates the cumulative reward attained by an agent, the idea is to subtract the next-step Q-function from the current state Q-function to get the single-step reward. This relationship is captured by the Bellman equation. ↩

-

We prefer choosing the softmax action over the argmax action as it introduces stochasticity, leading to improved exploration and better generalization, a technique often referred to as soft Q-learning. ↩

-

Our trained AI agent is adept at finding caves and creating waterfalls. It is also good at building pens but often misses fully enclosing animals. It also can build messy incomplete house structures, although, often abandoning current builds and starting new ones. (it uses a small LSTM to encode history, and better mechanisms like self-attention can help improve the memory) ↩